The sun’s early morning rays cast a soft glow across the gently rolling countryside, silhouetting farm buildings and highlighting here and there pockets of mist still clinging to warm earth, and stubble in freshly plowed fields waiting to be seeded with their winter over crop.

The timing was uncanny, but I had just started to write this story when Donna called from the porch, “you have mail from France!” It must have been some tourist information I requested, I thought, and excitedly stopped writing. But I should have suspected from Donna’s smug grin that something was off kilter. To my disappointment it was the notification of a traffic fine! Who drives when we are touring is a bone of contention between the two of us. But I’ll be the first to admit that I am a terrible passenger and believe that the “Oh God” strap above the passenger door was specifically designed for my benefit.

As a consequence, I prefer to drive slowly to see tomorrow’s sunrise. I deliberately choose to deny my lovely, daring wife the thrill of downshifting and accelerating along the many cliffside serpentine roads we might encounter, as I cower in the passenger seat. There weren’t any cliffside drives in Brittany, but you get my drift. I can safely say we have different driving styles. Seriously, my wife is an excellent driver, it’s more about the extravagant fee per day the car rental companies charge for the extra driver than anything else, kinda. It was not a speeding ticket, but a moving violation caught by a traffic camera on a quiet Sunday morning in the sleepy French village of Saint-Jouan-de-I’Isle, deep in the heart of Brittany. I alone was to blame, but would have preferred asking forgiveness from a gendarme, then the robotic indifference of a traffic spy camera, and a letter months later in the mail. Though I will give credit to the French authorities for designing a user-friendly website, Amendes.gouv.fr, for paying fines online.

We arrived mid-morning in Josselin just as the first wave of walkers were completing a charity walk in support of Pink October, France’s breast cancer awareness month, along the towpath that followed the Oust River in front of the town’s ancient castle, the Château de Josselin. It was late October, but the first yellows and muted oranges of Autumn were just beginning to show and combined with the walker’s pink vests made for a very colorful sight under a brilliant blue sky.

There has been a castle on this spot in Josselin since the 11th century, but the chateau you see today dates from 1370. Early in the 1400s Alain VIII of Rohan inherited the castle and it has remained a House of Rohan estate for 600 years. The chateau suffered poorly during the 16th century French Wars of Religion, as Henry II of Rohan supported protestant Huguenots against the King of France and the Catholic church; five of its original nine towers were destroyed on the orders of Cardinal Richelieu. During the French Revolution the castle’s towers were used as a prison, but afterwards it sat abandoned until the mid-1800s when Duke Josselin X of Rohan piloted an extensive restoration.

Strolling against the current of walkers we crossed a bridge to Josselin’s Quartier Sainte-Croix and wandered along narrow lanes past ancient half-timbered buildings dating from the early 16th century. Some leaned precariously, like an elderly person requiring a cane, while others featured ornamental heads carved into exposed roof rafters for decoration. Following our philosophy of “walk a little, then café,” we enjoyed a rest at the Logis Hôtel du Château, and its location on the riverbank.

Returning to the village, we stopped mid-bridge to admire the view along the riverport’s quay. With a renaissance chateau, charming buildings and a beautiful river to stroll along, no wonder Josselin has received the very French distinction as a Petite Cité de Caractère, a small town of character. During the high season paddle boards, kayaks, and boats are available for rent to enjoy this tranquil stretch of water.

The Oust is a canalized river and is part of the 220-mile-long Canal de Nantes à Brest which traverses inland Brittany to connect the seaports of Nantes and Brest, on the Bay of Biscay. The old towpath which follows the canal’s course is also a popular route for cyclists and hikers. We thoroughly enjoyed our morning in Josselin, but truly the quaint village deserves more time, or an overnight stay to absorb its wonderful ambiance. Vannes awaited us, so we drove on.

We arrived in Vannes and found convenient parking along the Port de Vannes quay, in an underground garage, in time for a late lunch. The masts of sailboats, with their colors flying, rocked gently in the afternoon breeze, against the background of the port’s Place Gambetta, and its iconic 19th century sandstone colored, Haussmann styled buildings, with their distinctive dormer windows in their mansard roofs. It’s difficult to imagine from the size of this petite harbor located on a narrow stretch of water called La Marle, that Vannes is actually an inland seaport, and the economic engine that drove Vannes’ prosperity since the era of the Romans, two-thousand years earlier. It was a favored protected anchorage, located three-quarters of a mile inland from the Gulf of Morbihan, for Rome’s merchant fleet of oared galleons, and it facilitated trade in wine and olive oil from France to England, while ships returned with valuable tin, lead and copper. Today the Port de Vannes hosts recreational and tour boats, which offer day trips to the islands in the Gulf of Morbihan, where on a windy day you can still see restored siganots, Brittany’s iconic two masted, gaff rigged, wooden fishing schooners, that typically have red sails, plying the waves.

Surprisingly, for this far north, a row of palm trees separated the Place Gambetta from the harbor, and gave the area a delightful French Caribbean vibe, before leading to the historic citadel through the Saint-Vincent gate. There were numerous restaurants, bustling with activity, surrounding the harbor, and we chose to lunch at Le Daily Gourmand for its outside tables and seasonal menu.

Excited by our first impressions of Vannes, we roughly planned our four days in the ancient city and day trips to Suscinio Castle, and the Alignements de Carnac. One of the attributes we consider when choosing a destination for a multiple day stay is the walkability of a city and are there enough things to do to keep us busy. Vannes fit the description perfectly, offering me multiple routes to explore the city during my 6 a.m. walks, while Donna slept in.

The walk along the Promenade de la Rabine, “the alley planted with trees,” was one of these walks that started near the Place Gambetta and followed the long sliver of La Marla, down its right bank a half-mile, towards the newer commercial port and the Gulf of Morbihan. The idea for this tranquil public space first arose in 1687, and over the following centuries it has been widened and extended several times. Halfway back on the return route there is a pontoon footbridge across the marina to the more cosmopolitan left bank.

A short walk from the Place Gambetta, the 19th century faded away quickly as we approached the historic Château de l’Hermine, with its formal garden featuring the emblem of the L’Ordre de l’Hermine, a medieval chivalric order, worked into its landscaping, and the Remparts de Vannes. The ermine depicted might look like us like a flying weasel, but it’s a traditional symbol of Brittany that signifies nobility, courage, honesty, uncompromising integrity, and personal honor. The ancient order was revived by the Cultural Institute of Brittany in the 20th century to honor people who contribute to Breton culture. The château, built in 1785, is a beautiful example of 18th century French architecture, and operated as the Hôtel Lagorce until 1803. It was then used as a private mansion until the French State purchased it in 1876 and proceeded to use it as an Artillery School and barracks for the XIth Army Corps, treasury, and university.

But the more interesting history of the site begins in 1380 when the Dukes of Brittany decided to use Vannes as their seat of power and ordered a castle with moat built and the ramparts surrounding the town, first erected by the Romans in the 5th century, improved. It served several generations of Dukes as their main residence until the late 1400s when François II, the last Duke of Brittany, moved his court to Nantes. During the early 1600s, the now-old castle was dismantled for its stones, which were used to build the quay at the port.

Skip ahead to March 2024 and the18th century château is now owned by the City of Vannes and construction has begun to renovate it and add a new wing for a project that will eventually be the Vannes Museum of Fine Arts – Chateau de l’Hermine. While excavating for new footings, workers uncovered well preserved walls, parts of a moat with drawbridge, and evidence that the castle had been three to four stories tall and had indoor toilets. We visited Vannes shortly before this discovery, but still marvel at the amazing things out there that are yet to be rediscovered.

A little farther along the Jardin des Remparts has the longest remaining section the city’s ancient defensive wall, with gates and towers, as their backdrop. The formal gardens are beautiful, with more than 30,000 flowers planted each year. It’s a popular spot to relax and walk dogs along the banks of the La Marla River before it reaches the port. The gardens are also used several times throughout the year to host various fairs and most importantly, the Fêtes Historiques de Vannes every July 12-14th. It’s a huge, festive cosplay event that celebrates Vannes’ rich history, and spreads into the historic center, with craft demonstrations, and participants and visitors wearing medieval clothing. The Porte Poterne gate is near the gardens, and entering the city one night across worn cobblestones glistening in a cold rain was an experience that transported us back centuries.

Later that first day in Vannes we were thrilled when we arrived at the Hôtel Le Bretagne and were able to find inexpensive street parking directly in front of it. The hotel abutted the rampart’s Executioner Tower and was ideally located just outside the historic old town, between the Porte de la Prison and Porte Saint-Jean gates. Vannes’ architectural continuity is unique among cities in France as it escaped the destructive aerial bombings of WWII, which ravaged many towns throughout the country.

Consequently, it has kept its rich architectural history intact. This was evident as we rounded the first corner from our hotel and entered the ancient citadel under the narrow-arched Porte Saint-Jean gate. In its earlier years it was known as the Porte du Mené, the Door of the Executioner, because of its close proximity to the axeman’s place of work. Fittingly, his tower was only a short walk down the alley from the Cathédrale Saint-Pierre, for the priests to give prisoners their last rites.

Built atop the ruins of an ancient Roman church, Saint-Pierre commands the highest point in the old town and blends Romanesque, Gothic, and neo-Gothic styles, which is what happens when a church is constructed, remodeled, expanded and restored from 1020 until 1857, when the carving of the façade was finally completed. It’s beautiful inside and out.

A short walk away, many fine examples of Vannes’ colorful,15th century, half-timbered buildings surround the Place Henri IV. A map isn’t needed to explore the ancient citadel. Wandering or “walk a little, then café,” as we like to say, is the perfect approach to discovering the town’s architectural gems and enjoying Vannes. After all, what’s the rush?

Wednesday and Saturday have been the traditional market days in Vannes for decades and the streets of the historic center fill with activity as folks shop among vendors selling housewares, clothing, breads, pastries, fruits and vegetables, wine, meat, sausages and CHEESE! Our weakness. Fromagers offering samples of soft and hard goat, sheep and cow cheeses with various ageing enticed us all too easily to purchase their products. Shopping there was a sensory experience that had us wishing we had opted for an apartment stay just so we could cook.

There are also two permanent food halls within the old town, Halle Aux Poissons, the fish market – is located down a side street just beyond the Porte Saint Vincent gate as you enter the city from the harbor. And the Halle des Lices, a large market hall with about thirty shopkeepers that is open Tuesday to Sunday from 8 am to 2 pm. It’s also a good place for breakfast or lunch.

The market takes its name from the Place des Lices on which it stands, though during the 14th and 15th centuries the Dukes of Brittany held jousts and tournaments there, between the Tour du Connétable, built for the commander of the Duke’s army, and the original Château de l’Hermine. The Tour du Connétable is a substantial tower that was part of the defensive wall that encircled Vannes, but what we found interesting was that you can still see where other ramparts intersected with the tower but were removed to reconfigure the fortifications as the city grew over time.

Only thirty minutes away, the Alignements de Carnac were an easy day trip from Vannes. We drove along D196 and followed a 1.6 mile route that started in a wooded glen at Alignements du Petit-Ménec and passed the alignments in Kerlescan, Kermario, and Toulchignan before ending at Carnac. It was a fascinating area with many opportunities to stop, touch and walk through the fields with over 3000 prehistoric standing stones.

Arranged in rows across a rolling landscape, the alignments are thought to have been erected around 4000BC, predating the 2500BC Stonehenge. Little is known of the Mesolithic hunter-gatherers that are thought to have erected the stones.

But a later Brittany Arthurian myth associated with them holds that they were a marching legion of Roman soldiers turned to stone by the sorcerer Merlin. Away from the road there is also a cycling/walking path through the countryside that paralleled our route. Afterwards we drove along the Trinité-sur-Mer waterfront, which we found reminiscent of coastal Maine.

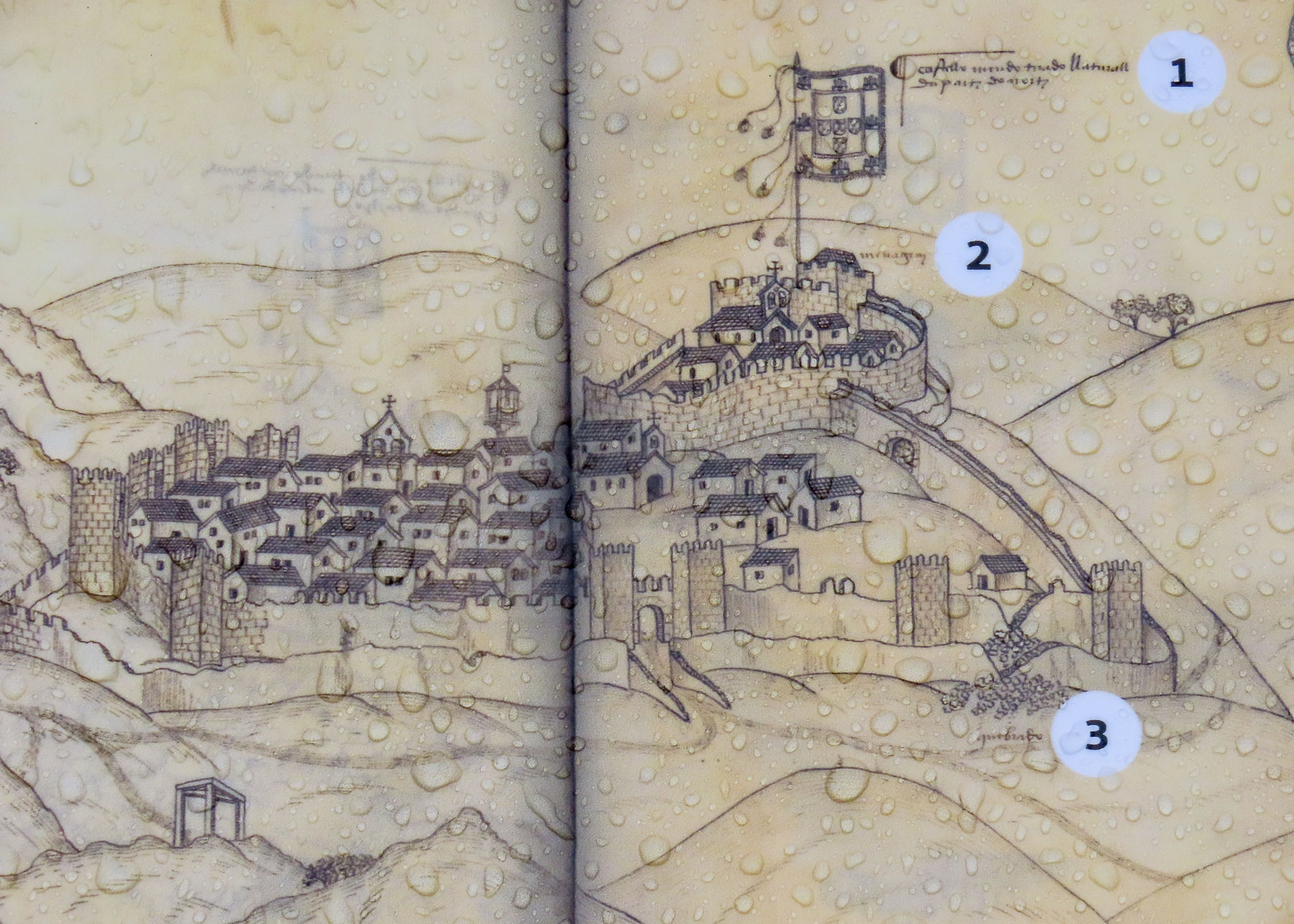

Another day we drove a half-hour south from Vannes to the Domaine de Suscinio, one of the prettiest castles in Brittany, near the Bay of Biscay. It started as a modest seigneurial manor house for Peter I, Duke of Brittany, in 1218. His son John I started to expand it and add fortifications, a building campaign that continued through successive Dukes until they moved their court to Vannes. Thereafter it was mostly used as a hunting lodge, unless there was a war in progress.

In the early 1500s it became the property of the French Crown and Francis I of France installed a favored mistress there. During the French Revolution, the now dilapidated castle was sold off to a stone quarry and its rocks were slowly carted away.

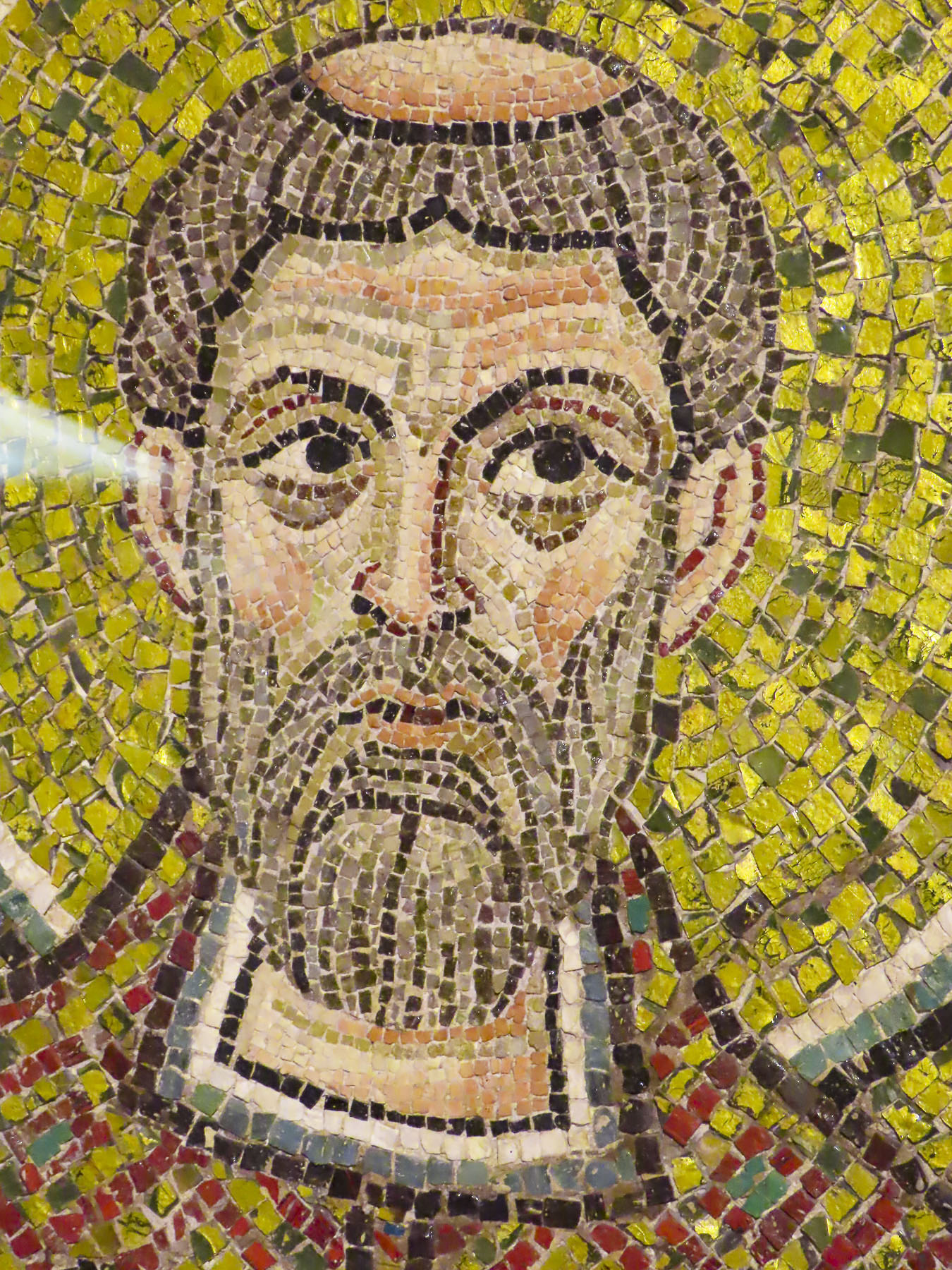

A dramatic restoration of the castle started in 1965, and was obviously a labor of love, that reflects the Bretonne pride in their heritage. It’s an exquisite space with many interesting, museum-quality displays. We thought the discovery of an intact, highly decorative, mosaic floor from the castle’s chapel, which was located across the moat, most intriguing.

Archeological excavations around the site are still ongoing and objects discovered, are restored and exhibited. Refreshingly there are plenty of hands-on things for kids to do, like dressing as Renaissance knights, squires or princesses. Medieval board games are also available for kids to try.

Beyond the ramparts there is a medieval encampment complete with re-enactors for families to explore. Wandering around the castle was thoroughly engaging and from the top of the battlements, you can see the Bay of Biscay. With the coast so close we wondered if Henry Tudor, future King Henry VII of England, landed there after he fled England, and spent 11 years in exile at Suscinio before returning to seize his crown in the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

Afterwards we headed to the Port du Crouesty marina in Arzon on the Peninsula Rhuys, surrounded by the Bay of Quiberon and Gulf of Morbihan. We sauntered along the port’s quay, admiring the boats docked in the marina, until we found Le Cap Horn. It was the perfect spot to enjoy some beers, and fresh seafood for dinner, our last meal in Brittany before heading home to the states.

We had a fantastic time exploring a small part of Brittany and hope one day to return to this charming, less explored, part of France.

Till next time, Craig & Donna

We’ve been on the road for more than 100 days now; previously, our longest trip was just shy of three weeks, with carry-on luggage only. So, we felt fully prepared to tackle this challenge (insert wink here.) Needless to say, there is a learning curve, but we have the right mind set. In late October, we move north to Guatemala, followed by a cruise to Cuba. The first part of 2019 will see us in Europe, and after that, who knows? We’ve discussed heading to South Africa, then working our way north and through East Africa, trying to have as many big game safari experiences as possible. This has been a dream of mine since I unwrapped my first National Geographic magazine and was enthralled by the spectacular images of the great migration across the Serengeti. Winning this

We’ve been on the road for more than 100 days now; previously, our longest trip was just shy of three weeks, with carry-on luggage only. So, we felt fully prepared to tackle this challenge (insert wink here.) Needless to say, there is a learning curve, but we have the right mind set. In late October, we move north to Guatemala, followed by a cruise to Cuba. The first part of 2019 will see us in Europe, and after that, who knows? We’ve discussed heading to South Africa, then working our way north and through East Africa, trying to have as many big game safari experiences as possible. This has been a dream of mine since I unwrapped my first National Geographic magazine and was enthralled by the spectacular images of the great migration across the Serengeti. Winning this