Overnight showers had cleansed the air, the morning was brilliant with sunshine, and the deep blue sky was checkered with fair weather clouds. We were road tripping west through flat farmlands and pasturelands, which were lined with rows of beech trees to protect the land from the ferocious winds of winter storms. The landscape was dotted with Normande, a breed of dairy cow descended from the cattle that the Vikings brought with them when they settled in the area during the 9th century. A white cow, speckled with brown patches, this breed is favored for its milk’s high fat content, which lends itself perfectly for making CHEESE! More specifically the PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) Camemberts, Livarots, Pont-l’Evêques and Neufchâtels that the Normandy region is famous for. Small signs for fromage and cider pointed down many dirt lanes that spurred off our route.

We were heading to the white cliffs of Fecamp and Yport, in the Seine-Maritime department of Normandy, on the English Channel. While planning this trip we read about high season – over-tourism running rampant across France. Crowds don’t appeal to us, so we’ve been planning our travels to coincide with a destination’s shoulder season for a while now. The articles also suggested visiting places off the usual tourist radar, which is how we came across Fecamp and Yport, our stops before reaching Étretat. In hindsight we should have planned a full afternoon or overnight stay in Fecamp, as the quick glimpses of the Palais Ducal, now ruins, and the Holy Trinity Abbey, as we drove through the historic center, revealed a pretty town and looked intriguing, worthy of further exploration.

Our “walk a little then café,” becomes “drive a little then café,” when we have wheels, and by the time we entered Fecamp it was time to satisfy that late morning craving. Parking in unfamiliar towns is always a challenge, and on a busy Saturday even more so, but we lucked out and found both a parking space and great café near the harbor. The sunny outside tables at Le Coffee de Clo were empty so we were surprised when we entered to see a lively shop nearly full of people busily enjoying the decadent sweet creations we had stumbled across. More muffin than pastry, the baked goods and excellent coffee here are the only excuse you need to detour to Fecamp.

Walking back to the car, we spotted the Chapelle Notre-Dame du Salut, across the harbor, high atop Cap Fagnet. It’s believed that Robert the Magnificent, an 11th century Duke of Normandy, constructed the church in thanks to God for surviving a shipwreck in the waters below the white cliffs of Cap Fagnet. It’s been a pilgrimage site for fishermen, sailors, and their families ever since.

The views from the terrace in front of the church of Fecamp’s harbor, and the southern half of La Côte d’Albâtre, the Alabaster Coast, take in an 80-mile stretch of white cliffs between Etretat and Dieppe on the Normandy coast, that mirrors the distant White Cliffs of Dover across the channel. Locally the cliffs around Fecamp are known as le Pays des Hautes Falaises, high cliff country.

In 1066, William of Normandy set sail from Fecamps’ harbor with a fleet of more than 700 ships, partly financed by the Abbott of Fecamp, to claim the Crown of England, which he had inherited, but this was being contested by Harold, a pretender to the throne. The issue was settled at the Battle of Hastings when the former became King William the Conqueror. It was also reassuring to learn that the Fecamp monks transitioned away from being international arms merchants, and segued into a more appropriate occupation – running a distillery in the 16th century, that produced a 27-herb flavored liqueur that would become popular in the mid-1800s and sold as Le Grand Bénédictine.

Eight hundred seventy-eight years after William set sail, on June 6, 1944, during WWII German fortifications along the Côte d’Albâtre failed against an allied amphibious invasion fleet of over 7000 ships and landing craft. It was the beginning of the end of WWII. Scrambling to the top of an abandoned bunker provided us with the perfect vantage point for photos of the coast.

By the time we arrived in Yport the clouds had thickened and were threatening to rain. To our dismay, it poured just as we were parking by the beach promenade. Fortunately, it was an intense but brief shower that cleared into a cloudless sky and revealed a quaint picturesque hamlet and shining white cliffs towering above the sea.

The cliffs along the seafront have been eroding for eons, creating in certain spots deep, long ravines that funneled torrents of water, laden with sand and stone through the cliff face to the ocean, which created beaches in certain places over the ages. These narrow valleys are called valleuses, and the small coastal fishing village of Yport started in one during the Neolithic era.

Without a harbor, fishermen pushed their small boats across a pebbled beach and rowed out through the waves to pursue their livelihood. They repaired their boats and mended their nets on the beach at the foot of the town. This way of life supported the villagers for centuries. Only the invention of the small outboard motor in the early 1900s eased their physical effort, until the 1960s when tourism and a small casino replaced fishing as the town’s driving economic force.

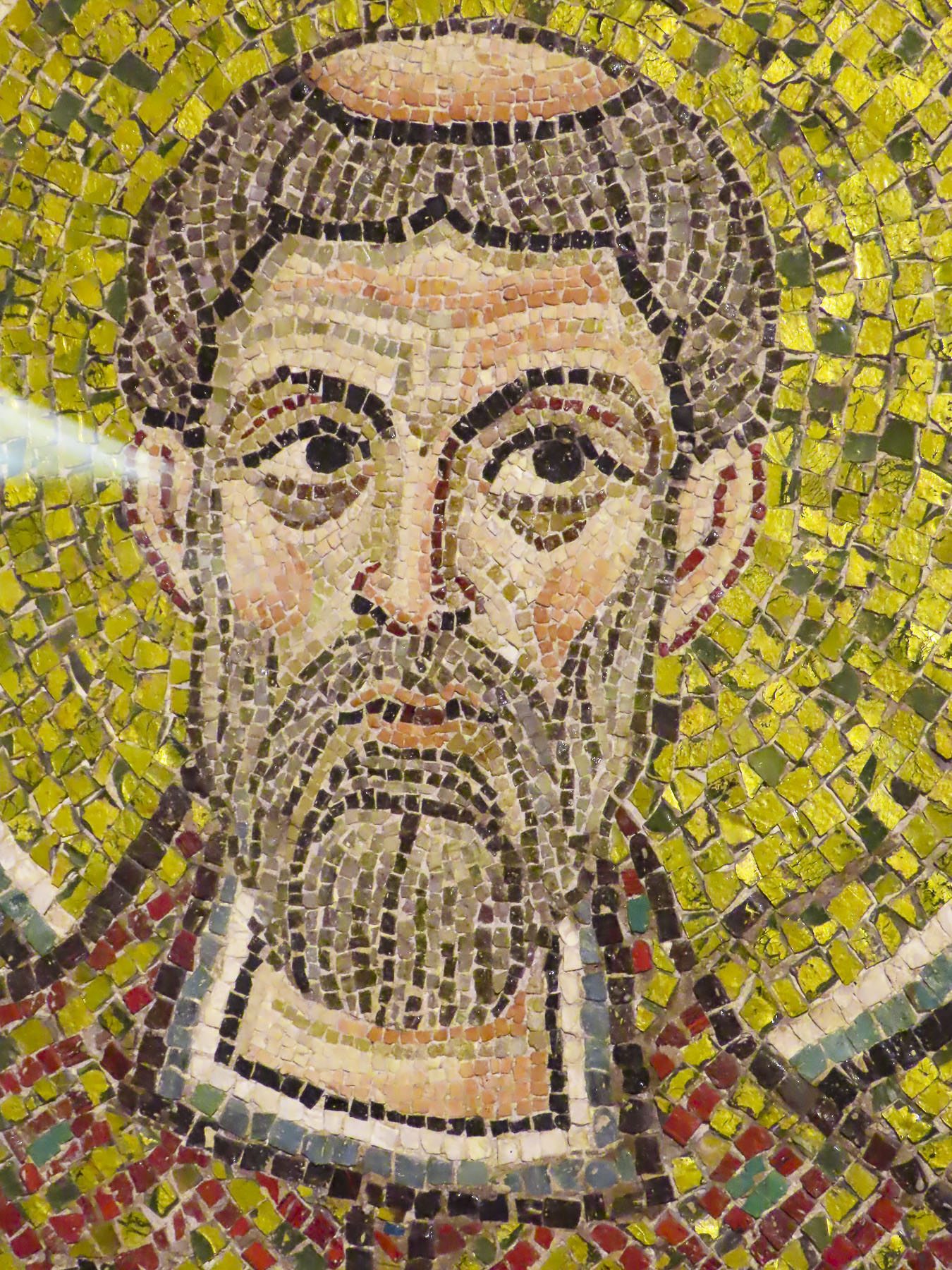

In 1838, the tightly knit community decided to build a church. Men, women, and children gathered tons of smooth stones from the beach, carted them 500m inland, and proudly worked together to mix cement and build the center piece of their town. Horizontally striped with alternating layers of colored beach stones, the façade of the church is beautiful, and unique in Normandy. It is a true testament to the power of community spirit.

By the mid-1800s Parisians seeking a more relaxing retreat than Etretat were frequenting the quiet fishing village. The French painters Monet, Renoir, Schuffenecker, and Vernier visited and painted there, while the 19th century French writer Guy de Maupassant set his novel, ‘Une Vie,’ in Yport. Paths from the center of the town and from behind the casino lead to the cliff tops and join the popular GR21 trail that can be followed north to Fecamp or south to Etretat.

Regardless of how beautiful photos of the Falaise d’Aval are, they don’t rival the physical reality of the calling gulls, wind-swept hair, the whistling wind and the relentless sound of the surf crashing against the stoney beach.

Arriving late on a Saturday afternoon in mid-October, we were surprised Étretat was jammed with tourists. Parking is extremely limited here and finding a space is almost a competitive sport that ultimately just required us to sit in a row and wait for someone to return to their car. It sorted itself quickly enough and luckily, we were only a short walk from one of Étretat’s first lodgings, the Hotel Le Rayon Vert, which to our delight was directly across from the beach and Étretat’s promenade. After checking in, we headed to the top of the towering 300ft high cliffs for sunset, the first of many walks along this beautiful stretch of coast and the perfect way to work up an appetite.

If you have been following this blog, you’ll know my superpower is the ability to find a great pâtisserie, pastelería or pastry shop. It’s a great talent when the hotel wants 16€ per person for breakfast. In Etretat, the boulangerie patisserie “Le Petit Accent” exceeded all expectations!

Set high above the town, it was a steep uphill walk to the Jardins d’Etretat. This whimsical topiary garden, with playful faces as “Drops of Rain,” by the Spanish artist Samuel Salcedo, more so than the Falaise d’Aval, was the catalyst for visiting this seaside resort.

This magical spot has its roots over 100 hundred years ago when a villa and garden were built here by Madame Thébault, a Parisian actress, and friend of the impressionist painter, Claude Monet. Madame Thébault cultivated a circle of creative folks as friends, and Monet along with other painters and writers were her frequent guests. It was from a patio in this garden that Monet found repeated inspiration to capture the essence Les Falaises à Étretat. His love of the area is evident in the nearly 90 canvases he painted depicting various scenes along the Normandy coast. But the Jardins d’Etretat today are a relatively new botanical masterpiece reopening in 2017 after an expansive reinterpretation led by the landscape architect, Alexander Grivko.

Across from the entrance to the garden, a tall soaring monument pointing skyward, elegant in its simplicity, commands a view out over the cliffs and the ocean beyond. This tribute commemorates the last sighting from French soil of the pilots Charles Nungesser and François Coli on May 8th, 1927. They were flying their biplane L’Oiseau Blanc, The White Bird, from Paris to New York in an attempt to be the first non-stop flight across the Atlantic Ocean and win the Orteig Prize of $25,000. But they disappeared somewhere along their route. It’s believed they made it across the Atlantic, but crashed into the dense wilderness forest of Nova Scotia or Maine. Wreckage of L’Oiseau Blanc has never been found and their disappearance remains an unsolved aviation mystery, that rivals Amelia Earhart’s story. If Nungesser and Coli had succeeded, they would have beaten Charles Lindbergh in the Spirit of St. Louis by twelve days.

The Notre Dame de la Garde stands alone on the slope below the Monument “L’Oiseau Blanc,” isolated on the cliffs like a small boat surrounded by a vast ocean, its spire like a lighthouse’s guiding beacon, visible far out at sea. It offers a welcome sign for the fishermen and sailors returning home. Unfortunately, it was undergoing renovation when we visited in mid-October.

Walking back through the village we found the Normandy architecture in Etretat intriguing. It encompasses many different styles and runs the gamut from ancient half-timbered buildings embellished with ornate wood carvings, to 18th and19th century designs utilizing the local hard flintstone and incorporating steep pitched slate roofs and turrets into their designs. All fascinating.

Etretat has been a popular destination since rail service began between the port city of Le Havre and Paris in 1847. Swimming or a day at the beach later became common place with the latest fashion, the full body bathing suits. While society folks were sunbathing on the stoney beach, there was a cottage industry of locals, called pebblers. They collected the beach stones for their high silicone content, which were then pulverized and used for various industrial purposes. It’s now illegal to remove any pebbles from the beach as they are vital natural protection against storm surges and marine submersion of the promenade built across the top of the beach, which is much easier walk on than trekking across the pebbly beach, where each footstep sinks into the loose stones and is exhausting to cross.

The classic 19th seaside resort continues to draw visitors, with the success of the French Netflix series Lupin, based on the writer Maurice Leblanc’s character, Arsène Lupin, the gentleman burglar. Leblanc’s former summer home, where he wrote some of his books, is now the Le Clos Arsène Lupin Museum. Some scenes were filmed locally, motivating a whole new generation to discover the white cliffs. The other French writers and composers who enjoyed their time in the quaint village include Victor Hugo, Guy de Maupassant, and Jacques Offenbach, all of whom are remembered with streets named in their honor.

We also enjoyed our time along the Côte d’Albâtre, but just seemed to scratch the surface of this beautiful part of Normandy.

Till next time, Craig & Donna

We’ve been on the road for more than 100 days now; previously, our longest trip was just shy of three weeks, with carry-on luggage only. So, we felt fully prepared to tackle this challenge (insert wink here.) Needless to say, there is a learning curve, but we have the right mind set. In late October, we move north to Guatemala, followed by a cruise to Cuba. The first part of 2019 will see us in Europe, and after that, who knows? We’ve discussed heading to South Africa, then working our way north and through East Africa, trying to have as many big game safari experiences as possible. This has been a dream of mine since I unwrapped my first National Geographic magazine and was enthralled by the spectacular images of the great migration across the Serengeti. Winning this

We’ve been on the road for more than 100 days now; previously, our longest trip was just shy of three weeks, with carry-on luggage only. So, we felt fully prepared to tackle this challenge (insert wink here.) Needless to say, there is a learning curve, but we have the right mind set. In late October, we move north to Guatemala, followed by a cruise to Cuba. The first part of 2019 will see us in Europe, and after that, who knows? We’ve discussed heading to South Africa, then working our way north and through East Africa, trying to have as many big game safari experiences as possible. This has been a dream of mine since I unwrapped my first National Geographic magazine and was enthralled by the spectacular images of the great migration across the Serengeti. Winning this