The ferry vibrated gently as the engines were switched into reverse as we approached the Buquebus ferry terminal in Buenos Aires. We had departed earlier from Montevideo, Uruguay, and hoped to view the Argentinian coastline from the Río de la Plata estuary, as the first Spanish explorers did in the early years of the 16th century. But we hadn’t expected the ferry not to have an open observation deck, and instead had to contend with the view, or lack of view, through hazy saltwater-etched windows.

Seasoned travelers on this route between Montevideo and Buenos Aires had already called for the ride share services of Cabify, inDriver, Didi, Easy Taxi or BA Taxi and waited curbside in front of the terminal. By the time the ferry docked there were no available drivers for 45 minutes. We were among the last to leave the port that morning.

Our first impressions of this wonderfully cosmopolitan city were formed along the 16-lane wide – yes, 16 lanes – Av. 9 de Julio. Despite its width it is a pleasant tree-and park-lined esplanade, that extends for 27 blocks through the city and reminded us of the area around Central Park in Manhattan. Older buildings from the 18th and 19th century shared the skyline with more modern buildings than we expected, as well as the first of many street murals dedicated to the football player Lionel Messi #10 for Argentina national football team, and the country’s superstar at the moment. The sidewalks were bustling with activity. We wondered how we would ever cross 16 lanes of traffic on foot.

Our hotel for the next six nights, Urban Suites Recoleta, was across the street from Buenos Aire’s historic Cementerio de la Recoleta. We soon learned that most landmarks and hotels in the neighborhood ended with Recoleta in their name. The cemetery from our balcony looked like an ancient lost city.

The next morning, we explored the immediate neighborhood around the hotel that was full of activity with delivery trucks off-loading produce and dog walkers leading their packs of small dogs to the parks. We eventually crossed the Puente Peatonal Dr. Alfredo Roque Vítolo, a brightly painted footbridge across the roadway that connects the parks around the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes to the Universidad de Buenos Aires. The Facultad de Derecho subway station is located at the foot of the bridge. It is a terminus on the H-Line, one of Subte’s (from Subterráneo de Buenos Aires) six lines, that can get you nearly anywhere in this sprawling metropolis. Opened in 1913, Buenos Aires had the first subway in South America.

The Floralis Generica, a unique abstract aluminum sculpture, an iconic symbol of the city, centered the Plaza de las Naciones Unidas next to the school. The 23m (75ft) tall mechanical flower with six petals which opens in the morning and closes at night was a gift to the city by the Argentine architect Eduardo Catalano in 2002. Walking paths circled the sculpture and offered different viewing perspectives of the flower that the sculptor visualized to “represent all the flowers in the world.”

Walking back towards our hotel we veered down Avenida Alvear, seven blocks that were once Buenos Aire’s Park Ave or Champs-Élysées at the turn of the 20th century. It is known for the art nouveau-influenced Belle Époque architecture of the old mansions along the street that have now been converted into hotels and embassies. Unfortunately, many of the building facades were hidden by the trees that line the street.

Long before Starbucks was a thing, the Porteños, “people of the port,” as the citizens of Buenos Aires are called, developed a strong coffee culture that coincided with the arrival of several waves of Italian immigrants that began in the mid-1800s. The result is a city where it’s nearly impossible to get a bad cup of coffee. One block over from Avenida Alvear on Av. Pres. Manuel Quintana our “walk a little then café” philosophy was easily satisfied at La Fleur de Sartí, Confiserié Monet, and Cafe Quintana 460, where espresso-based coffee drinks rule.

When we travel, our mid-afternoon lunch tends to be our big meal of the day, so we end up looking for supermarkets to buy crackers, cheese and fruit to snack on later. Near our hotel there was a large Carrefour Market on Av. Vicente López. Around the corner from the supermarket was a block of traditional shops with two butcheries, a fish monger, fruit stands, and a cheese store. Though our best find in the neighborhood was Möoi Recoleta, which had a pleasing interior and excellent food. To our surprise it’s part of a small local restaurant chain.

That afternoon we timed our visit to the Cementerio de la Recoleta after the surge of the morning’s tour buses had departed. It’s a huge cemetery with a labyrinth of narrow passages through the grand mausoleums of Buenos Aires’ who’s who of notable citizens and wealthy families.

Some were very well kept, while others were under renovation, and a number appeared forgotten, with their doors broken and façades crumbling, as if the family line had ended or a once great fortune had been lost. One was highlighted by a whimsical statue of a woman roller skating atop her own tomb.

Many had small bronze plaques attached to the side of their tomb, hinting at the deceased’s illustrious career. Several had death masks protruding from the side of their mausoleums. The first one we happened across suddenly as we rounded a corner, and the very life-like stone face protruding from the side of a tomb, literally scared the wits out of me.

Surprisingly, Evita Peron’s tomb was one of the simplest structures. Immortalized since the Broadway musical “Evita,” by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice opened its curtain in 1976, and the following 1996 movie starring Madonna, folks have been intrigued by the controversial legacy of Eva Duarte. It is the rags to riches story of a poor country girl, the illegitimate daughter of a wealthy rancher, who moved at the age of 15 to Buenos Aires and found fame as a radio and film actress, which resonated in the barrios of the “Paris of South America.” She found love at the age of 26, marrying 48-year-old Colonel Juan Perón, in 1945, two years before he was elected President of Argentina.

Passionate and combative, as Argentina’s First Lady she used her influence to champion social justice and worker’s labor rights, and was endeared to the less fortunate who saw her as the voice of the people. Her early death at the age of 33 from cancer saddened the nation and calls were made for her canonization. Flags across the country flew at half-mast for ten days. Blocks around the Presidential Palace were filled with mourners, and an estimated 3 million people watched the horsedrawn caisson carry her coffin through the streets of the city during her state funeral. Her embalmed body in its glass coffin was displayed for two years in her office in the Ministry of Labor building, as plans for a memorial that was taller than the Statue of Liberty were made.

After a 1955 military coup Juan Perón fled to exile in Spain, and the new military dictatorship secretly disappeared Evita’s corpse for 16 years. First it was secreted away in various locations across Buenos Aires until one “officer mistakenly shot his pregnant wife while guarding the corpse in his attic.” The military dictatorship then enlisted the “covert help of the Vatican” to hide her body away in a crypt in Milan, Italy’s famous Cimitero Monumentale, for 16 years under a false name. In protest “Where is the body of Eva Perón?” was spray painted on walls all across Argentina.

In 1971, Evita’s body was exhumed and flown to Spain where Juan Perón and his third wife allegedly kept the “coffin on display in their dining room.” In 1973 Peron returned to the Presidency of Argentina, with his third wife as Vice President, but died a year later. The saga continued to get weirder when an anti-dictator revolutionary group, the Montoneros, “stole the corpse of General Pedro Eugenio Aramburu, whom they had also previously kidnapped and assassinated,” to use as a bargaining chip to get the third Mrs. Peron to return Evita’s body to her beloved country. Subsequent governments have gone to great lengths to secure Evita’s hopefully final resting place, in a subterranean tomb with trap doors and false caskets to deter grave robbers, within her father’s Duarte family mausoleum in Cemeterio de la Ricoleto.

Across the street was the Gomero de la Recoleta – Árbol Histórico, a majestic 225-year-old rubber tree planted in 1800. Over the decades its huge buttress trunk has grown to support a 50m (164ft) wide canopy, with tree limbs so long that wooden poles and sculptures are needed to support their weight.

Behind it, we found a reprieve from the hot February afternoon, and an early dinner at Bartola, which served an excellent lemonade, and has pleasant décor along with a rooftop terrace.

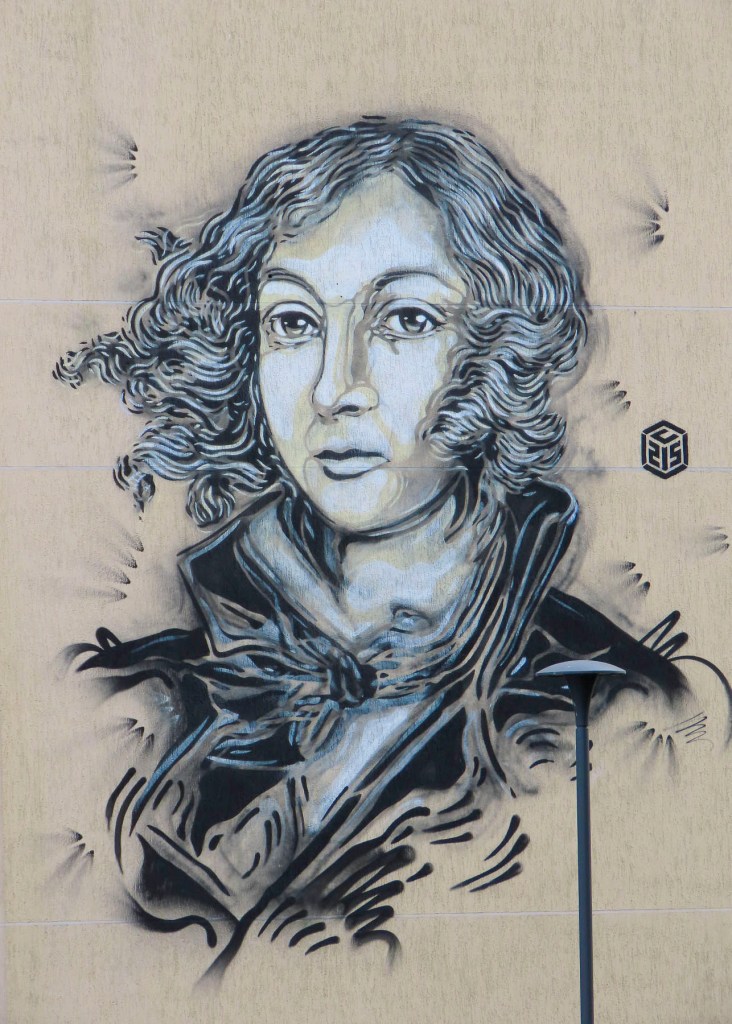

Buenos Aires is full of interesting street murals, and we spent the next morning wandering about searching for them.

That afternoon, after exploring farther afield from our hotel, we took a rideshare across the city to La Boca, a colorful neighborhood that is also the location of La Bombonera stadium, home of the world-famous Boca Juniors football club, the team on which some of Argentina’s legendary football players first played. Our route eventually took us below the elevated portion of Rt1 amidst a forest of concrete pilings painted with a vast array of creative street murals in an area named Silos Areneros. We found the area intriguing, but a tad sketchy, so we kept going.

La Boca was originally Buenos Aires’ first port at the mouth of the Riachuelo River, as it flows into the Río de la Plata. It has always been a bustling working-class neighborhood, “filled with all kinds of people, dockworkers, fishermen, musicians, prostitutes, thieves, socialists, anarchists, and artists.” But it grew substantially with the arrival of new immigrants in the 1800s and early 1900s. Hastily constructed tenements called conventillos were built with galvanized metal walls and roofs and brightly painted with whatever left over colors were available from the shipyards, in an effort to cheer up the area.

La Boca is one of the city’s vibrant neighborhoods where tango originated on its streets during the hot summer months and was perfected in the bars along Caminito and Magallanes during winters of the late 1800s.

Today, satirical figures adorn many of the balconies along Caminito and the adjacent streets, and poke fun at politicians, rival football teams or celebrities. Though we think you need to be Argentinian to fully appreciated the humor behind them.

A mural at the end of Caminito commemorates the Bomberos Voluntarios de La Boca (La Boca Volunteer Firefighters), Buenos Aires’ first fire brigade, formed in 1884.

Sadly, we found the wonderfully colorful area was oversaturated with cheap tourists’ shops heavily devoted to everything football, especially Lionel Messi’s #10 blue and white football shirt, which was available everywhere.

Afterwards we headed to the dockside area of Puerto Madero. Built in the late 18th century the port helped support Argentina’s economic growth during WWI and WWII as the country’s beef and food stocks were sent to a war-torn Europe. But the viability of the port declined as the size of merchant ships became larger and containerization took hold, until eventually the port was abandoned for many decades. A masterplan for the port’s redevelopment was realized in 1989 with plans to renovate some of the old warehouses along one side of the quay into restaurants and shops, while land on the other side would be developed into a mixed-use area of offices and residential towers, with the two sides connected by pedestrian-only bridge.

The redevelopment along the Puerto Madero waterfront was a great success and created a strikingly beautiful, new waterfront neighborhood. Its reflective skyline and restaurants along the old docks continue to be destinations for both locals and tourists. Us included! It was a great place to people watch as folks strolled along the quay and over the footbridge. Towering cumulonimbus clouds glowed with golden light, as the sunset silhouetted the “Presidente Sarmiento,” an old three-masted sailing ship that is now a nautical museum.

We both grew up in the suburbs of New Jersey and worked in New York City for a while, but living in Manhattan never appealed to us. It wasn’t until we started traveling and experienced living in some foreign cities through short-term rentals that we grew to appreciate the vitality that city life offers.

Mysteriously, overnight the Parque Intendente Torcuato de Alvear in front of the historic Centro Cultural Recoleta building was transformed into a sprawling art and crafts festival, that to our surprise happens every Saturday and Sunday. Artisans’ tents and tables lined nearly every path through the sprawling park that was filled with folks shopping and buskers playing to the crowd. This was probably the best crafts market we’ve been to, as the quality and variety of items offered were very impressive. If our suitcases had been bigger we would have made lots more purchases.

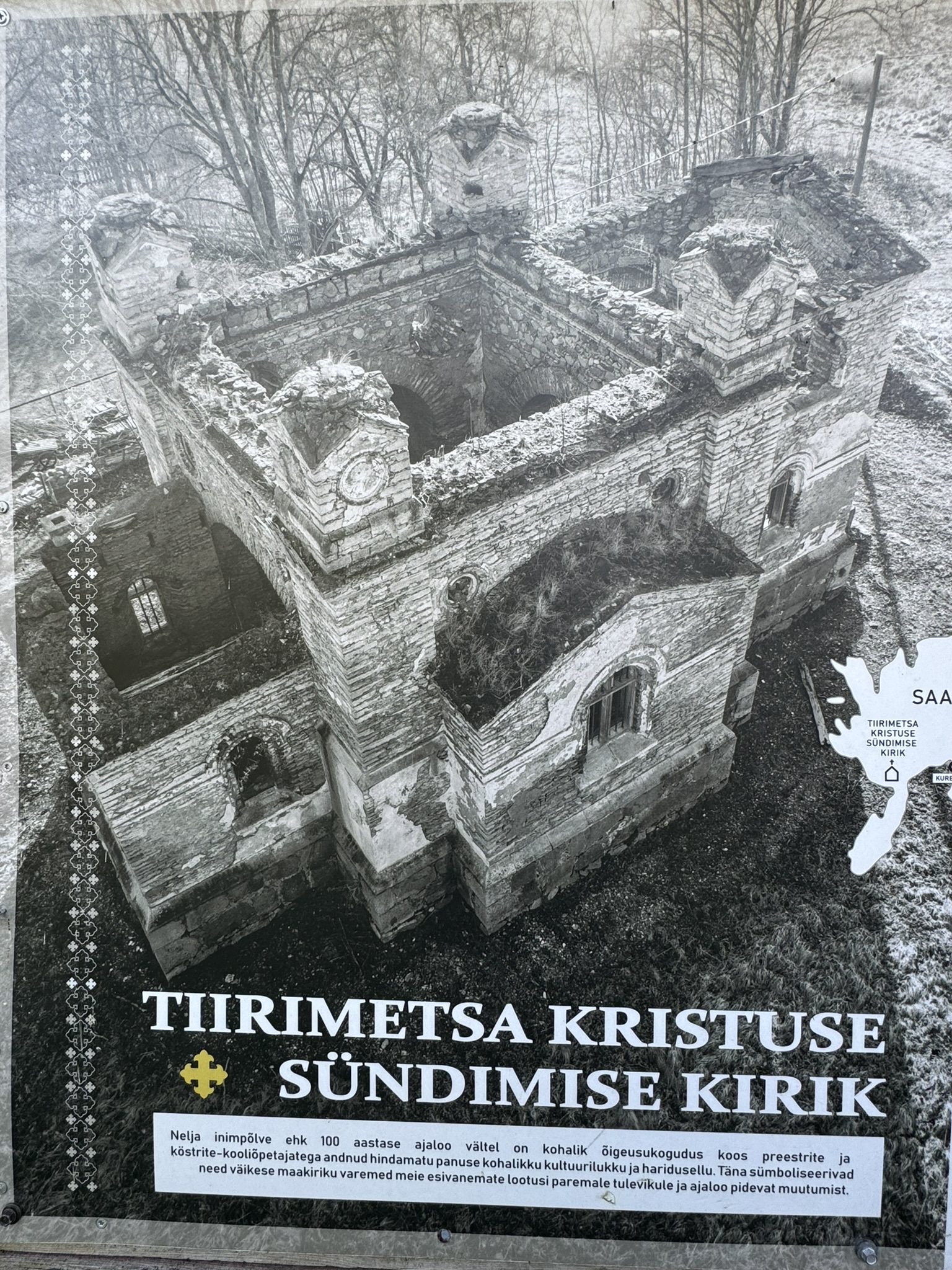

For many years the Cultural Center was repainted frequently with colorful murals, which added a nice flair to its otherwise stoic facade. Sadly, this policy was discontinued in 2024, and the building is now covered in a monochromatic “Pompeyan Red.” The decision has received a mixed public reaction, but hopefully the verdict will be reversed in the future. The historic 1732 building was originally the convent of the Recoleto monks, for whom the Recoleta neighborhood is named, as well as part of Our Lady of Pilar Basilica, the second oldest church in Buenos Aires. Over the decades as the influence of the church waned after Argentina’s 1810 May Revolution the building was used as a hospital, military barracks, asylum, and an art school before being renovated into an exhibits and events space in the 1980s.

That afternoon the tree lined blocks around Plaza Serrano and Plaza Armenia in the charming Palmero Soho neighborhood were so different from the high-rise towers of Recoleta, and reminded us of Barcelona & Madrid, with the wonderful mix of sidewalk cafés, along with trendy shops. Colorful street murals brightened many of the narrow alleys.

Across from Plaza Armenia we passed the Las Petunias restaurant which was full of lively diners at lunchtime. But we continued our wanderings and returned around 15:00 when the restaurant was quieter, though there were still enough other people dining to make it a nice experience. We shared Los Tablones de Carnes for two. The grilled meats were excellent, and it was the best parrillada we had during our stay in Buenos Aires.

Sunday, we headed to the Feria de San Telmo, a weekly street fair that spans eleven blocks of Av. Defensa, a street known for its antique stores and art galleries. San Telmo is one of the oldest neighborhoods in Buenos Aires and has striven to retain its 19th and early 20th century character with well-preserved buildings.

The street was full of activity, but the feira was really more like a flea market featuring clothing and everyday items with only a handful of artists’ and craftsperson’s tables mixed in between. Buskers worked the street corners, and a puppeteer dazzled a young audience. Occasionally a street mural graced a side street.

Along the way the ornate mausoleum of General Manuel Belgrano stood beneath the towers of Basílica Nuestra Señora del Rosario. The church was constructed in 1753 and British soldiers sought sanctuary here after a failed invasion of the city in 1807. General Belgrano was one of the founding fathers on Argentina’s independence and is also credited with designing the country’s flag.

The Mercado San Telmo was our destination for lunch. It is a cavernous hall set in an 1897 building that resembles a Victorian era train station with an ornate iron superstructure supporting a glass roof. The hall’s traditional produce stands, butchers and bakers, now share the space with takeaway restaurants, and antique stalls. But it was crazy with activity on a Sunday afternoon, and we vowed to return if we had the chance. Instead, we ate at Havanna, a small café chain across Buenos Aires, that we had eaten at the day before in Palmero Soho, and enjoyed.

Tango dancers were mesmerizing a crowd with their graceful twists, turns, dips, and kicks at the Plaza Dorrego. Resting between dances, they encouraged folks to come forward and dance too. It was a thoroughly enjoyable afternoon, with a vibe totally different from the craft market in Retiro, and the shaded lanes of Palmero. Every August the city hosts the Buenos Aires Tango Festival & World Cup, a two weeklong dance-off, with concerts and shows where over 400 couples from around the world compete for the top spots in different categories.

The next day a rainy morning finally cleared as we were on our way to a three hour cooking class to learn how to make those savory pastry meat-filled turnovers called empanadas, and alfajores, a melt in your mouth layered shortbread-like cookie filled with dulce de leche.

Our hosts Tomas and Lala graciously welcomed nine of us into their home; we were from France, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States. The other participants, like us, we learned after introductions all around, were snowbirds escaping a cold northern winter.

Tango music played softly in the background as Tomas divided us into three groups of 4, 2 and 3, the odd man out joining Donna and me. It was very well organized, and Tomas led us through the mixing of ingredients and made sure we added just the right amount of water so the dough was kneadable, but not sticky. Everyone cut their balls of dough and rolled them out into taco size discs, not too thin or too thick. Lala provided a meat filling. The hardest part was crimping the edges of the dough together to seal in the filling. The gal next to us was very good at it and created bakery worthy pockets. The three of us had various aesthetic results, that would improve with practice. Brushed with an egg white, trays of empanadas were put into the oven to bake. The cookie batter was also quite easy to make. We sipped some mate (a traditional herbal drink with lots of caffeine) and got to know our tablemates as we waited for the empanadas. We can see why people like mate (pronounced mah-tay) but I think for us it would be an acquired taste. The empanadas were tender and tasty, though it was obvious which ones my fingers had molded, as they oozed from some thin spots in the crust. This was the first cooking class we’ve ever taken during our travels and found the whole experience, along with the shared camaraderie, very enjoyable.

The next morning, we pulled our luggage behind us as we strolled down Calle Florida, a 10 block long pedestrian walkway in the center of Buenos Aire’s shopping district that runs from the Plaza General San Martín to Plaza de Mayo. It was a very pleasant lane centered with rows of young shade trees, and intermittent sidewalk cafes along the edges. The Galerías Pacífico, an upscale glass domed shopping complex, was our destination.

With architectural inspiration taken from the Vittorio Emmanuelle II galleries in Milan, the 1889 building was designed to be a shopping experience akin to the Bon Marche stores in Paris. But a long economic recession in Argentina during the 1890s and early 1900s nixed its realization and the gallery area was used as part of the National Museum of Fine Arts, while the Ferrocarril Buenos Aires al Pacífico acquired part of the building for offices. The company’s presence eventually led it to being called the “Edificio Pacífico,” (Pacífico Building).

The famous domed lower level over what is now the food court was constructed during renovations in the 1940s and embellished with twelve spectacular murals by the artists Lino Eneas Spilimbergo, Antonio Berni, Juan Carlos Castagnino, Manuel Colmeiro, and Demetrio Urruchúa.

A hundred years later a 1990s renovation finally covered the galleries with a glass ceiling and the “Galerías Pacífico,” became the flagship of Buenos Aires’ shopping district. We really are not into mall shopping, but this is very nice, and an architecturally and culturally interesting spot that attracts a diversity of folks. It was the perfect spot for our “walk a little then café,” break before having an ice cream bar decorated with Lionel Messi’s blue and white uniform. The Buquebus ferry terminal was only a short walk away for our crossing back to Uruguay and our flight home.

Buenos Aires is a sprawling city with 48 different neighborhoods and three million people. It is a great destination, and we only scratched the surface of the multitude of places to visit, and things to do within this vibrant city. In hindsight, we could have stayed several more days to explore the museums and government buildings, based ourselves in the Palermo neighborhood, and used the subway to get around.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna