After a three-day road trip through the colonial towns of Colonia del Sacramento and Carmelo, then the rural farmlands of Minas and ranchlands of Gorzon, the amount of activity around the traffic circle in Faro de José Ignacio took us by surprise. We had reached civilization again! Not that it was really busy, but literally more cars had passed us in the last five minutes than the last three days, as we pulled into the small collection of shops along Rt10, which leads up from Punta del Este. Some fruit and supplies were gathered for our four night stay at Casa Franca from the Devoto Market, a well-stocked, but typical beach town store that benefits from a captive market. A few doors down the Panadería José Ignacio, a popular bakery, has a very nice selection of bread, pastries and tasty delectables. They also have a pizza and sandwich counter along with tables for eating outside on their terrace. We returned every morning during our stay for fresh from the oven delights.

Folks parked along the road followed sandy paths across the dunes to the beach. The sails of kite surfers filled the sky as we passed the Laguana de José Ignacio, a freshwater lake separated from the South Atlantic Ocean by a sandbank, which it breaches when it rains too much.

Surf pounded against the Playa Balneario across from our host Daniel’s guesthouse in the tiny hamlet of Santa Mónica, only 5km (3mi) west of Faro de José Ignacio, but a sea change in tranquility, compared to our earlier shopping experience. His wife and children waved from their balcony as his friendly dog energetically greeted us. Daniel helped take our bags to our room, which was located through a private entrance to an extension on their home with three other guest rooms. While our chic petite studio didn’t face the ocean it did thankfully have a shaded porch, where we spent many hours.

After settling in we headed to the lighthouse in José Ignacio, located on thumb-like peninsula that juts into the South Atlantic. Its 32m (105ft) tall lighthouse has guided sailors off this treacherous reef coast since 1877.

While Punta del Este has been promoted as a beach resort for wealthy Argentinians and Uruguayans since the early 1900s, and is now known as the “Ibiza of Uruguay”. José Ignacio remained a quiet isolated fishing village without running water or electricity, as the coastal road from Punta ended at the Laguana de José Ignacio. All that changed in 1981 with the construction of a bridge across the lagoon. The infrastructure improvements that came at that time were appreciated, but the town’s small population rallied to prevent the coastal area from becoming a Miami-esque playground, and successfully petitioned the local government to enact ordinances to ensure its quiet, peaceful character remained intact by allowing only single-family homes, no taller than two-stories within the Maldonado region. Along with banning discothèques, pubs and nightclubs, as well as all motorized vehicles on the beaches, jet skis and speedboats are also prohibited in the lagoons. Today the town’s seven miles of pristine beaches attract folks from all over who just want to unwind along what many consider the best part of Uruguay’s 410-mile-long coastline.

We walked out onto the rocky point next to the lighthouse, then down a boardwalk over the dunes to the Playa Brava, a long gracefully curved stretch of sand, scoping out the best spots to return to the next morning for sunrise photos. We strolled along the wide beach between lifeguard chairs. Squealing kids ran into the surf from the beach speckled with blankets and sun umbrellas amidst impromptu volleyball and soccer games. We stopped at El Chiringo, an outdoor restaurant with tables in the sand and shared a pizza for an early dinner.

Heading back to Casa Francawe stopped along the lagoonto watch a beautiful sunset across its calm water. Kite Surfers unwilling to end their day skimmed along the water until it was nearly dark.

The next morning Donna slept in while I rose before dawn and drove back to the lighthouse to watch the sun cast its first rays of light across the rocky headland and lighthouse.

A few hardy fishermen had already made their first casts of the day from the rocks. On the other side of the lighthouse a group of fishermen were readying two large skiffs to push into the surf from the beach. Next to them the first surfer of the day paddled out, and a few joggers pounded along the cool sand in early morning solitude.

After a day of rest and relaxation we wanted to explore the beach towns farther east along the coast as it runs towards Brazil. The weather doesn’t always cooperate, but we were hopeful the sky would clear as we drove along Rt 9 near Rocha. There were a good number of produce stalls along the road hoping to entice travelers to the beaches to shop. We stopped at one with shelves stacked full with jars of local honey, jams, and Dulce de Leche, along with wheels of artisanal cheeses. We purchased a Dambo, similar to Edam or Gouda. It is a traditional local cheese made with the milk from grass fed cows which graze freely in the palm tree studded, pampas rangelands, that define the region. Farther up the road we stopped for our “drive a little then café,” break at a small shop attached to a gas station in the uniquely named town, 19 de Abril. The town takes its name from an event related the revolutionaries called the Thirty-Three Orientals, who returned from their exile in Argentina on April 19, 1825, an event that eventually started the Cisplatine War, which led to Uruguay’s independence from Brazil.

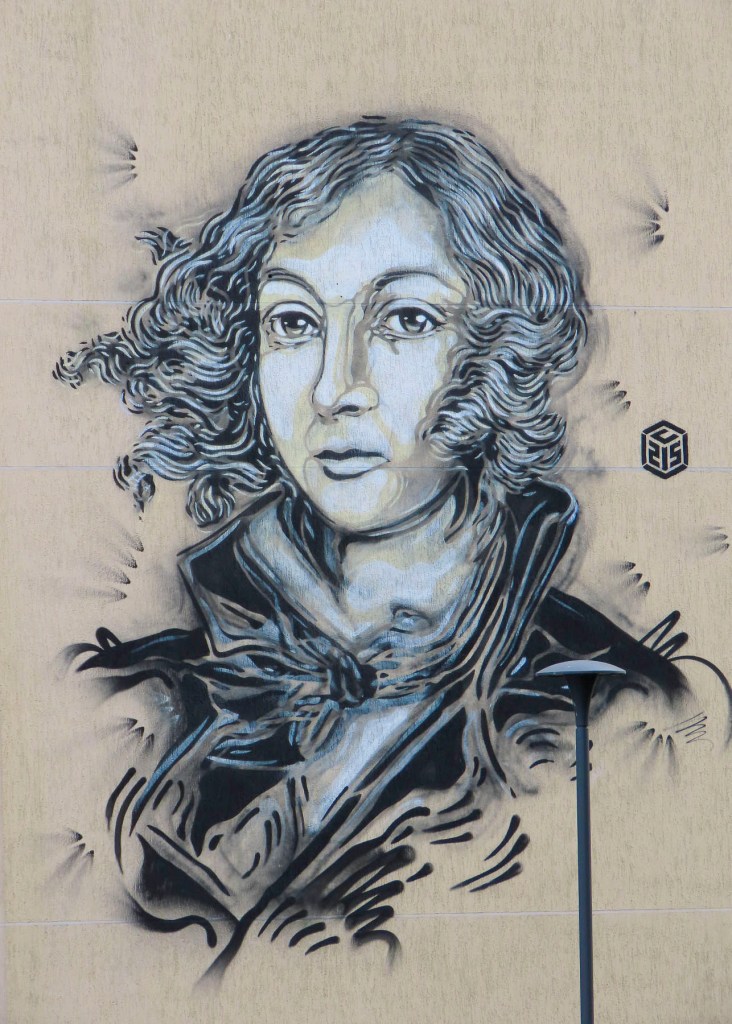

Normally in the states we avoid like the plague any eateries attached to gas stations, as they are typically places that just offer junk food, but route 9 traversed a semi-rural region, and there were few options. We were pleasantly surprised as we parked to see a mural of a painting by Simon Silva on the side wall of the café. We bought a poster of this image twenty years ago and it still hangs in our home, and it was nice to know that someone else enjoys the image as much as we do. The café Parador 19 de Abril delighted us. It’s a quaint oasis in the wilderness. The cappuccinos and fresh pastries were quite good, and the folks who ran it were very nice.

Folks were slipping and sliding through streams of water that were gushing down the hardpacked sandy roads of Punta del Diablo, as a deluge had descended upon us since our coffee break. The rain was too heavy to wander about, but we contented ourselves with driving through the haphazard layout of the oldest part of the rustic fishing village, that now has brightly painted shops and restaurants but is reminiscent of a village being founded by survivors of a shipwreck, using whatever materials they could salvage from the sea. Taking a horse drawn cart across the dunes was the only way to reach the once isolated village, until a road connecting it to Rt 9 was built in 1968. Larger flat bottomed fishing boats were beached along the gentle curve of Playa del Rivero, awaiting their next awaiting their launch at the arrival of high tide. A fisherman under a rain tarp offered his morning catch. Often during the Uruguay’s winter, June to November, the deep ocean just offshore allows folks to spot humpback and southern right whales breaching from the town’s beaches as they migrate north to the warmer waters around Brazil.

By the time we reached Aguas Dulces the rain had stopped, though the sky was still threatening, and the streets were nearly deserted. The high tide was rough from the earlier storm and was inching its way towards the row of boulders placed along the shoreline to prevent further coastal erosion and homes being swept away. Laidback and low keyed, Aguas Dulces is a budget-friendly destination for Uruguayan families who enjoy its lifeguard protected beaches when the weather cooperates.

On the way to La Paloma we stopped at Puente Valizas, a picturesque riverside fishing village along the Arroyo Valizas. The tributary flows 10km (6mi) from the Laguana Castillos to the Atlantic Ocean, near the beach resort of Barra de Valizas. The river was busy with fishermen speeding to the Laguana to catch pink shrimp, which thrive in the brackish waters of the lagoon, for the restaurants along the coast.

In La Paloma the afternoon sky was brightening as we walked along the Paseo Marítimo, a boardwalk through the dunes that lined the tranquil waters of Bahía Grande, a small clam shell shaped bay. La Paloma is the largest coastal town east of Punta del Este and is a popular resort area with 20km (12mi) of beaches that are suitable for surfers and families with young children to enjoy. Eventually we reached El Faro del Cabo Santa Maria, the town’s historic 42m (138 ft) tall lighthouse. Built in 1874, the powerful navigational beacon atop the tower can be seen 37km (23mi) out to sea. When it is open, folks can climb 143 steps to the top for some spectacular views of the coast.

On the way back to Faro de José Ignacio we followed Rt10 across the Laguna Garzón Bridge, an experience that totally took us by surprise, as the 2015 bridge has a unique circular design that resembles a flat donut. It’s really quite unusual but was designed this way to naturally slow the speed of traffic.

Our host and his family the next morning departed for a day trip a few minutes ahead of us. Their dog which watched their leaving from the second-floor deck had somehow escaped and was running frantically around outside the gated area. Fortunately, Donna has mastered that universal dog-call kissing sound, and we were able to lock him securely behind the gate. We called Daniel to let him know.

A few blocks down we stopped to photograph two abandoned properties. They were both very interesting, and we always wonder what the backstory is that goes with these places.

Route 10 hugs the beautiful 33km (20mi) stretch of wild undeveloped coast that extends from Faro de José Ignacio to Punta del Esta.

Reaching the outskirts of Punta we got our first glimpse of the Puente de la barra, a whimsical wavy bridge, that our route followed across the Arroyo Maldonado. Designed in 1965 to force drivers to reduce their speed, it’s said the rollercoaster-like bridge can cause vertigo if you drive too fast across it. On the Punta side there is a traffic circle that made it too easy for us to cross the bridge multiple times, just for the fun of it.

We stopped at a mirador near the “La Ola Celeste,” a stylized sculpture of a wave that overlooks the fast rolling breakers that beat against the waters of the Arroyo Maldonado as the river empties into the sea, and separates Punta from the smaller resort town of La Barra, which has a vibrant nightlife that rivals Punta’s as the best place to party in Uruguay.

This was also a great spot to get an expansive view of the dramatic beaches along the coast and Punta’s modern skyline, which often prompts folks to refer to it as “the St. Tropez or Monaco of South America.” The vista reminded us of Miami Beach.

We stopped for lunch at the Aura Beach House, a small modern café with a light menu, set on the brilliant white sand of Playa La Brava. They also have several rows of lounge chairs under nicely thatched beach umbrellas for daily rent. It was a beautiful, relaxing spot and our food and coffees were excellent; we didn’t want to leave. We found in our travels across Uruguay that street parking was always free, even along the beaches, something that is very rare in the United States.

We weren’t sure what the weather was going to be like the next day, so we took advantage of the splendid afternoon and stopped at The Hand, Punta’s most iconic landmark since the Chilean artist Mario Irarrázabal installed it along the oceanfront in 1982. It was very crowded with a tour group, but we waited for their departure before taking any photos. As it turned out the sculpture was within walking distance of our hotel, and we returned to it several times during our stay in Punta.

We continued on our way to the Faro de Punta del Este lighthouse that stands on the highest point of the narrow peninsula that was Old Town Punta, a whaling port established in the early 1800s.

Punta, like Montevideo, has a lot of public art on the streets we realized as we drove by the Monumento El Rapto de Europa. The large bronze sculpture references the myth of Europa, a Phoenician princess who was abducted by Zeus in the form of a bull and taken to the island of Crete. Why it is on a street corner near the beach in Punta, we haven’t a clue. Across the street from the lighthouse were several architecturally interesting homes and the very blue Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria church which had a lovely tranquil interior.

At Punta’s modern marina, sleek motor yachts and sailboats now bob gently in the water where the whaling ships once anchored. The first tourists to Punta arrived in the early 1900s, but it wasn’t until the infrastructure improvements of the 1940’s supported the construction of modern hotels and the town’s first casino that Punta’s reputation as a luxurious destination in South America was cemented. We stayed in the Old Town at Hotel Romimar, a budget-friendly lodging with an excellent breakfast, off Av. Juan Gorlero, Punta’s main shopping street.

We love exploring a new city early in the morning as it wakes up. By 7:30 beach attendants were hard at work carrying lounge chairs and umbrellas from trailers parked along the street, down to the sand and assembling them into tidy rows for their expected sunbathers. It was the perfect time to re-visit The Hand, as the sun was just cresting over its fingertips, and sunlight was reflecting brightly off the row of high-rise condos that fronted the coastline.

Wandering about we spotted several cachilas, old cars that out of economic necessity were lovingly maintained and passed forward through hard times. Some are now totally restored and look as good as the day they rolled out of the showroom. One, an old Plymouth, was creatively covered in a mosaic pattern of old Uruguayan coins.

Families were also out early to claim their preferred batches of sand at Playa El Emir, a small beach on the edge of Old Town Punta with a wonderful view of the coastline, near the Ermita Virgen de la Candelaria. The shrine to the patron virgin of Punta del Este is located on a narrow sliver of land that juts into the South Atlantic Ocean, that is believed to be where the Spanish explorer Juan Díaz de Solís held a mass when he landed nearby in 1516. Our “walk a little the café,” breaks were satisfied that morning with excellent coffee and pastries at Donut City and Cresta Café. Both were only a short walk from the beach.

A day trip the next morning took us to towns west along the coast from Punta that also interested us. Our first stop was at the Escultura Cola de la Ballena Franca, an open wire metal sculpture of a whale tail that overlooks the ocean between the endless beaches of Playa Mansa and Playa Cantamar. It is a popular lookout spot for southern right whales during the peak of their winter migration between July and October.

Casapueblo is a surreal Guadi structure that captures the essence of the whitewashed cliffside homes on the Mediterranean island of Santorini, Greece. It started as a small wooden shack in 1958, the studio of Páez Vilaró, a Uruguayan abstract artist. He expanded it himself along the oceanfront as his family grew, and friends like Picasso and Brigitte Bardot visited, until a whimsical 13-story structure with 72 rooms stacked upon each other covered the cliff face. Today it is a museum and hotel.

Afterwards we drove to the Laguana del Sauce and enjoyed a quiet lunch overlooking the lagoon from the Hotel Del Lago.

Away from the oceanside a rural landscape quickly unfolded as we drove through farmlands to the Capilla Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, a pretty church that reminded us of settings in the American Midwest.

The next morning, our last full day in Uruguay, we headed west toward the Canelones wine region near Montevideo, an area which produces nearly fifty percent of Uruguayan wines at vineyards which were started four to five generations ago by families which immigrated from Europe. Piriápolis is a small coastal city which grew from a private investment as the country’s first planned resort was along our route. El Balneario del Porvenir (the Resort of the Future) was the vision of Francisco Piria, a wealthy Uruguayan businessman, who in 1890 bought 2700 hectares (6672 acres) of undeveloped land along a beautiful beach, 99km (62mi) from Montevideo. He spent forty years commissioning hotels and a promenade along the oceanfront, which he likened to the French Riviera, before his death in 1933. In 1937 the population of the resort town was large enough to be declared a pueblo, and twenty-three years later it achieved the status of a city. From the landing of a small chapel atop Cerro San Antonio we had a perfect panoramic view of the city that still draws visitors to its beach where families can rent scooter cars for their children to wheel along the promenade. During the high season the Aerosillas Piriápolis chairlift whisks tourist from the marina to the top of the hill. The Castillo de Francisco Piria, the entrepreneur’s home, was on the outskirts of the city as we headed to a wine tasting and overnight stay at the Pizzorno Winery & Lodge.

We arrived at the winery as a tractor pulling a wagon full of just-harvested grapes was being unloaded into a destemmer-crusher, the first step in the long process to create wine.

Founded in 1910, the fourth generation of the Pizzorno family operates the wine estate. It has 21 hectares (52 acres) of vineyards planted with Tannat, Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Malbec, Arinarnoa, Marselan, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, and Muscat of Hamburg vines.

We were the only guests that afternoon during the last week of February and thoroughly enjoyed the interesting tour of the wine cellar led by Joaquin, the winery’s sommelier. He explained their viticulture philosophy which endorses “traditionally harvesting grapes by hand, respect for the ecosystem, environmental conservation through a no fertilization and watering wisely policy, along with green pruning, leaf removal, and bunch thinning to obtain the best grapes, which is reflected in the quality of the wines we make using only our own grapes.”

Afterwards Joaquin’s experience continued to enhance our tasting of four wines as he shared his knowledge of the vineyard’s terroir, and the different grape varietals, along with their aromas, flavors, and recommended pairings with food.

It was our last night of our 15-day trip around Uruguay and we treated ourselves to a luxurious stay in the winery’s posada. It was for many years the family home until it was creatively restored into an attractive boutique inn with four guest rooms overlooking a pool and the vineyards.

“You will have the posada all to yourselves tonight. Enjoy the pool, and feel free to walk through the vineyard. A nightwatchman will arrive later.” The golden hour was upon the vineyard as we cooled off in the pool.

This surely dates us, but it felt like we were in an episode of the TV show Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous hosted by Robin Leach, who used to sign-off with “Champagne wishes and caviar dreams.”

Till next time,

Craig & Donna