Background:

Why Ethiopia? After 14 months of continuous, slow travel, spent mostly exploring cities, we were ready for a change of pace and a more raw or “authentic” experience, for lack of a better phrase. We had planned to visit Ethiopia originally just to see the hand-hewn rock churches of Lalibela. But, with a tough spousal negotiation, we reached détente: three months in the land of her people, Italy, and for me, 12 days bouncing on backroads and possibly camping a night or two in a tribal village, and a cross country adventure through the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and People’s Region which includes the Omo Valley. An exciting itinerary with Ephrem Girmachew of Southern Ethiopia Tours fit the bill and our budget. I’m not sure who got the better deal, but somewhere along our journey we coined the phrase “shaken tourist syndrome” to reflect the road conditions we encountered for hours each day.  The area in the northern part of the Greater Rift Valley, known today as the Omo Valley region of Ethiopia, has been at the crossroads of humankind for many millennia. In 1967 Dr. Leaky discovered fossil bone evidence, recently re-dated by scientists to be 195,000 years old, of early Homo sapiens near Kibish, Ethiopia, several miles west of the Omo River near where the borders of Sudan, Kenya and Ethiopia meet. The first migrations of early man out of Africa occurred 60,000 years ago as they followed the Omo River north through the Great Rift Valley to the Red Sea. At its narrowest point, where it meets the Gulf of Aden, they crossed to continue their migration through Arabia and eventually into Europe and Asia. The region was once rich with African wildlife, and Arab towns along the northern East African coast of Somalia and Kenyan were sending hunting parties into the interior for elephant ivory, rhino horn and unfortunately slaves since around AD 1000.

The area in the northern part of the Greater Rift Valley, known today as the Omo Valley region of Ethiopia, has been at the crossroads of humankind for many millennia. In 1967 Dr. Leaky discovered fossil bone evidence, recently re-dated by scientists to be 195,000 years old, of early Homo sapiens near Kibish, Ethiopia, several miles west of the Omo River near where the borders of Sudan, Kenya and Ethiopia meet. The first migrations of early man out of Africa occurred 60,000 years ago as they followed the Omo River north through the Great Rift Valley to the Red Sea. At its narrowest point, where it meets the Gulf of Aden, they crossed to continue their migration through Arabia and eventually into Europe and Asia. The region was once rich with African wildlife, and Arab towns along the northern East African coast of Somalia and Kenyan were sending hunting parties into the interior for elephant ivory, rhino horn and unfortunately slaves since around AD 1000.

It is thought that the Mursi and Suri tribes developed lip plates and scarification as a way to discourage Arab slavers from taking their women. The first European contact with the region is credited to Antonio Fernandes, a Portuguese Jesuit missionary, who was sent by Ethiopian Emperor Susenyos in 1613 to find an inland route, that avoided all Islamic territories, to Malindi, a Portuguese port at the time, on the Indian Ocean. The next reported western explorers to the region were Antonio Cecchi in the 1870’s and Vittorio Bottego in 1897. Bottego was the first European to follow the Omo River all the way to Lake Turkana, at a time when Italy was trying to become a colonial power and expand its Italian Eritrea territory into Ethiopia. By the early 1900’s teams of cultural anthropologists from various Europeans countries were viewing the area as the “last frontier” and beginning to study the “cultural crossroads” aspect of the tribes of the Omo Valley.

A harsh, vast territory, the semi-arid Omo Valley is home to 13 indigenous groups that are seminomadic pastoralist. These tribes also practice flood retreat cultivation along the banks of the Omo River, to produce crops mostly for subsistence or occasional trading in the local markets. Very remote and undeveloped, the area resisted Ethiopian Orthodox influence from the north of the country for centuries. It wasn’t until the 1990’s, when a fledgling tourist industry began to emerge, and violent cross-border conflicts with various nomadic tribes looking for better grazing or to rustle cattle, that the government began to exert influence over the area. Some nomadic tribes along the border were encouraged to settle down and farm and fish along the Omo River for their livelihood. Government interest in the area was intensified again when the decision to build two dams on the Gibe River, a tributary of the Omo River, were built to supply hydroelectric power to Ethiopia. Later, the massisve Gibe lll dam, completed in 2016, was built to supply irrigation water to foreign owned sugar cane and cotton plantations on lands that were seized by the Ethiopian government from the indigenous tribes of the Omo Valley. Consequently, as the natural cycle of the river flooding was stopped, the centuries old practice of flood retreat farming is failing as there is not enough rainfall in the area to support crops. This has increased tensions amongst tribes already competing for limited grazing and fertile farming lands due to climate change.  Things change, but the proud peoples that live in the Omo Valley are trying to retain their way of life amidst external influences they can’t control, as tourists and construction crews course across their territory. Tempers flare when trucks and buses carrying supplies and workers to the agricultural plantations strike and kill cattle. Drivers are required to stop and immediately pay the herder for his loss, but many never do. Consequently, the local tribe will block the road and demand payment until the issue is resolved.

Things change, but the proud peoples that live in the Omo Valley are trying to retain their way of life amidst external influences they can’t control, as tourists and construction crews course across their territory. Tempers flare when trucks and buses carrying supplies and workers to the agricultural plantations strike and kill cattle. Drivers are required to stop and immediately pay the herder for his loss, but many never do. Consequently, the local tribe will block the road and demand payment until the issue is resolved.

The Beginning:

It was immediately apparent as we were landing that Ethiopia was different. Addis Ababa is a thriving city of almost 5 million people, with gleaming skyscrapers, a new sprawling economic development zone, and high-speed rail line connecting the city to Djibouti. With no suburban transitional zone, the city was an island surrounded by an ocean of farmland.  A good night’s sleep at the Jupiter International Hotel Bole (they have the best front desk staff we’ve encountered) made an early start bearable. Meeting us punctually, an amiable Ephrem introduced us to Gee and his trusty Toyota Landcruiser. We could tell from the beginning that they were friends and had worked together for years. Even before leaving the city limits, we met our first of the ubiquitous cattle herds, donkey carts and tuk-tuks slowing our passage.

A good night’s sleep at the Jupiter International Hotel Bole (they have the best front desk staff we’ve encountered) made an early start bearable. Meeting us punctually, an amiable Ephrem introduced us to Gee and his trusty Toyota Landcruiser. We could tell from the beginning that they were friends and had worked together for years. Even before leaving the city limits, we met our first of the ubiquitous cattle herds, donkey carts and tuk-tuks slowing our passage.

Our first day would be the longest with over eight hours of driving to Arba Minch, that included a stop at the archaeological site of Tiya Stelae. Here a large field of stelae were adorned with carvings of spears; the number of spear heads on a stone is thought to represent the number of enemy killed. Other stones that dotted the landscape contained symbols that were more difficult to interpret. Nothing is really known about the people that created these monuments and there are no other sites in the area to help archeologists explain their mystery.

Further along, we stopped at an explosion of color and activity that represents an Ethiopian local market, our first of many. Coming from our last stop in parched Zimbabwe, this landscape was unexpectantly and refreshingly green. We passed farmers plowing theirs fields with oxen, the way it has been done for centuries. The 2019 rainy season was good; unfortunately, this is often not the case. There was no water infrastructure in most of the small towns and villages we passed through, forcing folks to gather water from local streams and rivers.

The 2019 rainy season was good; unfortunately, this is often not the case. There was no water infrastructure in most of the small towns and villages we passed through, forcing folks to gather water from local streams and rivers. It was a constant sight: women carrying yellow water jugs along the side of the road back to their homes, or if they could afford it, having it delivered by donkey cart. The terrain varied tremendously, with full rivers on one side of a mountain range and dry on the other side. These conditions forced people to dig into the riverbed in search of water.

It was a constant sight: women carrying yellow water jugs along the side of the road back to their homes, or if they could afford it, having it delivered by donkey cart. The terrain varied tremendously, with full rivers on one side of a mountain range and dry on the other side. These conditions forced people to dig into the riverbed in search of water.

Closer to Arba Minch workers piled just-cut bananas onto trucks, from plantations that lined the road. Since Ethiopia is close to the equator, the daylight hours do not vary seasonally. The sun rises quickly in the morning and seems to drop from the sky at the end of the day. By the time we reached the Paradise Lodge in Arba Minch darkness was falling. It was a long walk to our room, and signs along the path warned of baboons and warthogs. A mosquito netted bed welcomed us under a single light bulb dangling from the ceiling. A dramatic dawn the next morning through clearing storm clouds revealed the hotel’s placement on a cliff edge above a lush, dense forest that was part of Národní Park Nechisar that surrounds the perpetually brown Abaya Lake and Chamo Lake off in the distance below.

Since Ethiopia is close to the equator, the daylight hours do not vary seasonally. The sun rises quickly in the morning and seems to drop from the sky at the end of the day. By the time we reached the Paradise Lodge in Arba Minch darkness was falling. It was a long walk to our room, and signs along the path warned of baboons and warthogs. A mosquito netted bed welcomed us under a single light bulb dangling from the ceiling. A dramatic dawn the next morning through clearing storm clouds revealed the hotel’s placement on a cliff edge above a lush, dense forest that was part of Národní Park Nechisar that surrounds the perpetually brown Abaya Lake and Chamo Lake off in the distance below.  At breakfast we watched thick-billed ravens in aerial combat as they rode the thermals just off the restaurant’s terrace. Nearby a staff member stood ready to chase away baboons if they got too close to the customers’ tables.

At breakfast we watched thick-billed ravens in aerial combat as they rode the thermals just off the restaurant’s terrace. Nearby a staff member stood ready to chase away baboons if they got too close to the customers’ tables.

After breakfast we headed into the highlands northwest of Arba Minch to visit the Gamo tribe in the Dorze village. The Dorze, Doko and Ochello are the three clans that comprise the Gamo people. Rising slowly to an elevation of 8200ft, we traveled through heavily forested slopes that opened to patches of verdant farmland, and occasionally passed small groups of children dancing to earn spending money from passing tourists. As we entered the village, compounds ringed with woven rattan walls held back tall Enset plants, better known as false banana, also called the “tree against hunger.” This plant is an important staple that is drought resistant and can be harvested year-round. Starch from the plant is scraped from its fibers and fermented in the ground for three months or longer and used to make kocho, a type of flat bread.

As we entered the village, compounds ringed with woven rattan walls held back tall Enset plants, better known as false banana, also called the “tree against hunger.” This plant is an important staple that is drought resistant and can be harvested year-round. Starch from the plant is scraped from its fibers and fermented in the ground for three months or longer and used to make kocho, a type of flat bread.  Fibers from the plant are used to make rope or coffee bean bags, and the leaves are fed to farm animals. We arrived on market day, and an entire hillside about the size of three football fields was covered with activity. From a distance it looked like an animated impressionistic painting, with undulating dots of color dancing under a blue sky.

Fibers from the plant are used to make rope or coffee bean bags, and the leaves are fed to farm animals. We arrived on market day, and an entire hillside about the size of three football fields was covered with activity. From a distance it looked like an animated impressionistic painting, with undulating dots of color dancing under a blue sky.  Sellers of charcoal, sugarcane, vegetables, and a multitude of other goods all had their wares spread out on cloths covering the ground. Men played foosball or ping-pong under the few shade trees that ringed the field.

Sellers of charcoal, sugarcane, vegetables, and a multitude of other goods all had their wares spread out on cloths covering the ground. Men played foosball or ping-pong under the few shade trees that ringed the field.

The Dorze are known for the family structures they build, called elephant huts, and the fine weavings that they create from the cotton they grow. Constructed of hardwood poles, bamboo, thatch and enset, the huts get their name from the symmetrical vents at the top create a silhouette that resembles an elephant’s head. These towering huts can last eighty years, and when the bottom of the main poles become termite-infested they are cut off and the hut is then lifted up and moved to a different spot in the family compound. Men of the Dorze tribe traditionally do the weaving, while the women are responsible for spinning the cotton that the family grows and uses. The colorful textiles they create are highly prized all over the country.

Men of the Dorze tribe traditionally do the weaving, while the women are responsible for spinning the cotton that the family grows and uses. The colorful textiles they create are highly prized all over the country. Back in Arba Minch we stopped at the Lemlem restaurant for a lunch of local lake fish before checking out the crocodiles on Chamo Lake. The lightly fried fish were served whole, while the sides were scored into squares which we picked off with our fingers. It was delicious. Another side of the restaurant served freshly butchered, grilled meat.

Back in Arba Minch we stopped at the Lemlem restaurant for a lunch of local lake fish before checking out the crocodiles on Chamo Lake. The lightly fried fish were served whole, while the sides were scored into squares which we picked off with our fingers. It was delicious. Another side of the restaurant served freshly butchered, grilled meat.

The road south of Arba Minch cut through farmland. Stately fish eagles and traditional Ethiopian honeybee hives dotted some of the trees along the road. The elongated beehives are made from hollowed out logs and wrapped with woven bamboo strips, and then suspended in the trees.

It’s a dangerous livelihood, fishing the muddy waters of Chamo Lake, as attested to by the size of the Nile crocodile that swam alongside our tour boat. He was frightfully as large as our 18ft vessel. Crocodile hunting hasn’t been allowed in the lake since 1973, so there are many big old crocs in its waters. Every year fishermen are killed while standing in the lake casting their nets. Those who can afford to, buy boats to fish. Full immersion baptisms are performed by some churches in Chamo and Abaya Lakes, and tragically, in 2018 a Protestant pastor was snatched by a crocodile and killed in front of his congregation during a baptismal celebration.

“Tomorrow we drive to Kenya,” Ephrem offered. Really? That wasn’t expected! “We will stop before we actually get to the border to see a Singing Well of the Borena tribe, and then head to Chew Bet, an extinct volcanic crater lake where the tribe takes black salt from its water.” “Sorry for the late pick-up, but the road was full of tuk-tuks carrying families to the university stadium up the street for a graduation ceremony,” Ephrem offered as he bundled us into the Land Cruiser and handed us large bottles of water. “It’s hot where we are going today.”

“Sorry for the late pick-up, but the road was full of tuk-tuks carrying families to the university stadium up the street for a graduation ceremony,” Ephrem offered as he bundled us into the Land Cruiser and handed us large bottles of water. “It’s hot where we are going today.”

Crossing a small mountain range as we headed south from Arba Minch, we left the green landscape behind us and descended into a semi-arid savanna of acacia trees and thorn scrub that held ostrich and huge termite mounds. Soon we encountered our first herd of camels being prodded along by young herders. In Yebelo we stopped to pick-up a local Borena guide who accompanied us for the rest of the day. Now speeding toward the border, we passed isolated huts and folks seemingly in the middle of nowhere walking to unseen destinations. We abruptly u-turned when our guide spotted the dirt track we needed to follow to the tula, a centuries-old deep well that continues to be dug deeper into the ground as the water table drops. We trailed a young Borena girl herding a small group of cattle down a slowly inclined, dusty trench deeper into the earth. It was impossible to avoid cow patties as we steered clear of an exiting herd. Thirty feet below the surface, the trench ended in a bowl shape with a water trough where cattle were drinking. Rhythmic voices emerged from a shallow cave behind the trough. Climbing worn stone steps, we came to a narrow landing above the trough, where below us men sang to set a pace to their work. (Click the preceding link to see the video.) They lifted heavy buckets of water over their heads to others above them who then dumped the water into the trough for the cattle to drink. The acoustics of the cave increased the sound of their songs.

We trailed a young Borena girl herding a small group of cattle down a slowly inclined, dusty trench deeper into the earth. It was impossible to avoid cow patties as we steered clear of an exiting herd. Thirty feet below the surface, the trench ended in a bowl shape with a water trough where cattle were drinking. Rhythmic voices emerged from a shallow cave behind the trough. Climbing worn stone steps, we came to a narrow landing above the trough, where below us men sang to set a pace to their work. (Click the preceding link to see the video.) They lifted heavy buckets of water over their heads to others above them who then dumped the water into the trough for the cattle to drink. The acoustics of the cave increased the sound of their songs.

This was the wide, higher part of the well. At the back of the cave there was a hole, only as wide as a man with a bucket, that descended straight down another sixty feet into the earth where more tribesmen worked in unison to lift water up from the bottom of the shaft. Every day for centuries, teams of men have worked in thirteen tulas spread across the Borena territory to keep the tribe’s cattle alive in a harsh land where there is very little surface water. Imagine one of the most inhospitable places on earth and you might envision the village of Soda, located on the rim of the mile wide El Sod crater. Aside from raising cattle, goats and camels, some Borena tribesmen have given up their pastoral life to dive into the depths of the El Sod Crater Lake to collect salt, which is then dried and traded or sold across southern Ethiopia from Somalia to Sudan and down into Kenya. It takes the salt divers an hour to descend the narrow track to the lake surface, 1100 ft below the crater’s rim. After scraping 50lbs of wet salt from the lake bottom, they bag it and load it on donkeys for the 1.5 hour walk out of the crater, only to turn around and do it again as many times a day as they can. Black and white salt along with crystals are gathered in the lake. Crystal salt is the most valuable, and black salt, used for animals, is the least.

Imagine one of the most inhospitable places on earth and you might envision the village of Soda, located on the rim of the mile wide El Sod crater. Aside from raising cattle, goats and camels, some Borena tribesmen have given up their pastoral life to dive into the depths of the El Sod Crater Lake to collect salt, which is then dried and traded or sold across southern Ethiopia from Somalia to Sudan and down into Kenya. It takes the salt divers an hour to descend the narrow track to the lake surface, 1100 ft below the crater’s rim. After scraping 50lbs of wet salt from the lake bottom, they bag it and load it on donkeys for the 1.5 hour walk out of the crater, only to turn around and do it again as many times a day as they can. Black and white salt along with crystals are gathered in the lake. Crystal salt is the most valuable, and black salt, used for animals, is the least.

Each diver works for himself and it is a tragically difficult livelihood. Many of the divers suffering from loss of hearing and sense of smell, tooth decay, eczema and blindness from spending years in the highly concentrated, corrosive salt water. No eye protection is worn and nose and ear plugs are rudimentarily, made from plastic bags stuffed with dirt. At the crater rim the salt is sold to middlemen who dry it in slatted wooden shacks before reselling it. Trucks have now replaced legendary camel caravans which once crisscrossed the savanna to remote villages.

After lunch and our first Ethiopian coffee ceremony, we headed to the Yabelo Wildlife Sanctuary, a 1600 square mile grassland preserve that is mostly home to Grevy’s and Burchell’s zebra. Walking with our local scout, we were able to slowly approach a small herd of zebra. Some of the females were heavy with calves soon to be born. A short drive away, our last stop of the day was a well-kept Borena village surrounded by an ochre landscape under a perfect blue sky. Women do the heavy lifting in the villages, building the huts, tending children and crops, and spending a substantial amount of time foraging for firewood and gathering water from far off sources. While the men spend their days moving their cattle across different grazing lands.

A short drive away, our last stop of the day was a well-kept Borena village surrounded by an ochre landscape under a perfect blue sky. Women do the heavy lifting in the villages, building the huts, tending children and crops, and spending a substantial amount of time foraging for firewood and gathering water from far off sources. While the men spend their days moving their cattle across different grazing lands. Women rule their homes and determine who can enter, even prohibiting spouses. “If her husband comes back and finds another man’s spear stuck into the ground outside her house, he cannot go in,” our guide conveyed.

Women rule their homes and determine who can enter, even prohibiting spouses. “If her husband comes back and finds another man’s spear stuck into the ground outside her house, he cannot go in,” our guide conveyed.

Away from the village as we headed back to Arba Minch we spotted both Grant’s and giraffe-necked Gerenuk gazelles. The latter rises on its hind legs to feed on higher vegetation.

Old ways are changing as the Ethiopian government shows more interest in the south, and while Animism is still practiced, Christianity and Islam are making inroads into the region.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna

Please share my page with your friends

Walking, walking, walking! The countryside is full of folks out and about on their feet. There is a rural minibus network connecting larger villages once a day, and Lalibela has tuk-tuks, of course. But mostly, whether it’s due to lack of affordability or availability, people walk to and from everywhere. Sometimes it is necessary to travel great distances to accomplish simple, everyday tasks like gathering water, heading out to tend a remote field, going to market, or even farther to visit a doctor.

Walking, walking, walking! The countryside is full of folks out and about on their feet. There is a rural minibus network connecting larger villages once a day, and Lalibela has tuk-tuks, of course. But mostly, whether it’s due to lack of affordability or availability, people walk to and from everywhere. Sometimes it is necessary to travel great distances to accomplish simple, everyday tasks like gathering water, heading out to tend a remote field, going to market, or even farther to visit a doctor.  In the rugged agrarian highlands surrounding Lalibela, all the fields are tilled by farmers walking behind teams of oxen, as it has been done for centuries, on farmland passed down through a communal hereditary system called rist.

In the rugged agrarian highlands surrounding Lalibela, all the fields are tilled by farmers walking behind teams of oxen, as it has been done for centuries, on farmland passed down through a communal hereditary system called rist.

We started our day listening to bird calls and watching the morning clouds burn off from the valley below our hotel as the sun rose higher into the sky. The

We started our day listening to bird calls and watching the morning clouds burn off from the valley below our hotel as the sun rose higher into the sky. The

The shops were busy, and the roadside Ping-Pong games were in full swing as we departed Lalibela. The road into the mountains rose quickly from Lalibela into a semi-forested landscape. Too steep for crops, the land was used for cattle, which grazed on clumps of wild grasses on the hillside. We stopped at one clearing for the view and noticed a herder gently nudging his cows away from recently planted tree seedlings. “This is part of our government’s commitment to reverse deforestation and help mitigate climate change. It’s called the

The shops were busy, and the roadside Ping-Pong games were in full swing as we departed Lalibela. The road into the mountains rose quickly from Lalibela into a semi-forested landscape. Too steep for crops, the land was used for cattle, which grazed on clumps of wild grasses on the hillside. We stopped at one clearing for the view and noticed a herder gently nudging his cows away from recently planted tree seedlings. “This is part of our government’s commitment to reverse deforestation and help mitigate climate change. It’s called the  “On July 29th Ethiopians planted 350 million trees in a single day, a world record!” he proudly shared. “The farmers know how important this is and help shoo the cattle away, but the government has also chosen a tree seedling that doesn’t taste good.” This annual Ethiopian project is part of the African Union’s

“On July 29th Ethiopians planted 350 million trees in a single day, a world record!” he proudly shared. “The farmers know how important this is and help shoo the cattle away, but the government has also chosen a tree seedling that doesn’t taste good.” This annual Ethiopian project is part of the African Union’s  The road deteriorated after this, with deep mudded ruts tossing us from side to side regardless of how slowly we navigated through, over or around them. Our “rattled tourist syndrome” is the most appropriate way to describe the ride, while optimists might refer to it as an an “African deep tissue massage.” We were the only truck to park at the trailhead to the Asheten Mariam Monastery and were greeted with children selling handicrafts, and young men renting walking sticks and offering to accompany us on the hike.

The road deteriorated after this, with deep mudded ruts tossing us from side to side regardless of how slowly we navigated through, over or around them. Our “rattled tourist syndrome” is the most appropriate way to describe the ride, while optimists might refer to it as an an “African deep tissue massage.” We were the only truck to park at the trailhead to the Asheten Mariam Monastery and were greeted with children selling handicrafts, and young men renting walking sticks and offering to accompany us on the hike. Confident in our abilities we declined, but they tagged along anyway. This was a good thing. What our guide had forgotten to mention was that there was a short steep section at the beginning of the hike, before it leveled off. Within minutes, between the altitude and the terrain, our hearts were pumping and my wife, who struggles with asthma, was gasping for breath. We are unfortunately not the 7 second 0-60mph vroom, vroom of a 1964 Corvette anymore, but more like the putt-putt of a classic Citroën 2CV. We get there, eventually. So, our guide, forgetting his youth and our age, led the way from a distance, as if he was channeling

Confident in our abilities we declined, but they tagged along anyway. This was a good thing. What our guide had forgotten to mention was that there was a short steep section at the beginning of the hike, before it leveled off. Within minutes, between the altitude and the terrain, our hearts were pumping and my wife, who struggles with asthma, was gasping for breath. We are unfortunately not the 7 second 0-60mph vroom, vroom of a 1964 Corvette anymore, but more like the putt-putt of a classic Citroën 2CV. We get there, eventually. So, our guide, forgetting his youth and our age, led the way from a distance, as if he was channeling  It was at this point that my wife spoke up. “Girma, you must think of me as the same age as your mother.” Instantly, his attitude became very solicitous, and he smilingly offered her a hand or other assistance at every opportunity. We marveled at the agility of the local kids. They nimbly scampered up and down the trail, easily outdistancing us, in order to set up their little trailside displays of carvings and beadednecklaces. When we didn’t purchase at first, they simply packed up and reappeared further up the trail. We had to reward such perseverance with a couple of purchases.

It was at this point that my wife spoke up. “Girma, you must think of me as the same age as your mother.” Instantly, his attitude became very solicitous, and he smilingly offered her a hand or other assistance at every opportunity. We marveled at the agility of the local kids. They nimbly scampered up and down the trail, easily outdistancing us, in order to set up their little trailside displays of carvings and beadednecklaces. When we didn’t purchase at first, they simply packed up and reappeared further up the trail. We had to reward such perseverance with a couple of purchases. Meanwhile, we regained our pace as the trail leveled off and tracked along the base of a cliff face that fell away to terraced farmland far below. The incline of the trail continued to rise; the walking sticks were now invaluable in helping us steady our footing on the rough path. Around a curve the trail abruptly narrowed at a sheer rock wall broken by a vertical chasm, slightly wider than our shoulders.

Meanwhile, we regained our pace as the trail leveled off and tracked along the base of a cliff face that fell away to terraced farmland far below. The incline of the trail continued to rise; the walking sticks were now invaluable in helping us steady our footing on the rough path. Around a curve the trail abruptly narrowed at a sheer rock wall broken by a vertical chasm, slightly wider than our shoulders.

Imprinted at the bottom of a page in one ancient text were the thumbprints of the ten scribes who helped copy the book. Legend has it that it was the first church ordered built by King Lalibela during his reign in the twelfth century and that his successor, Na’akueto La’ab, who only ruled for a short time, is buried there.

Imprinted at the bottom of a page in one ancient text were the thumbprints of the ten scribes who helped copy the book. Legend has it that it was the first church ordered built by King Lalibela during his reign in the twelfth century and that his successor, Na’akueto La’ab, who only ruled for a short time, is buried there.

Coming to the end of the road, we could see the monastery dramatically situated behind a small waterfall, in a long shallow cave at the bottom of a cliff.

Coming to the end of the road, we could see the monastery dramatically situated behind a small waterfall, in a long shallow cave at the bottom of a cliff.

Stone bowls smoothed from centuries of use sat in various places on the rough floor to collect the water seeping from the cave’s ceiling one drip at a time. It gets blessed by the priest and used as Holy water, continuing a tradition from the 12th century when King La’ab ordered the monastery’s creation.

Stone bowls smoothed from centuries of use sat in various places on the rough floor to collect the water seeping from the cave’s ceiling one drip at a time. It gets blessed by the priest and used as Holy water, continuing a tradition from the 12th century when King La’ab ordered the monastery’s creation.

In the learning area, layers of carpet attempted to smooth an uneven, rocky floor where the novitiates sit to learn the ways of the orthodox church. In the corner rested several large ceremonial drums used during worship services. Picking one up our guide beat out a rhythm that would normally accompany liturgical chanting, or Zema, by the young monks. We’ve noticed that the treasures of the Ethiopian churches are not determined by their monetary value and locked securely away, only to be used on religious holidays, but by their spiritual connection. Precious, irreplaceable, ancient bibles and manuscripts, lovingly worn and torn as they are, continue to be used every day, as they have been for the last nine-hundred-years.

In the learning area, layers of carpet attempted to smooth an uneven, rocky floor where the novitiates sit to learn the ways of the orthodox church. In the corner rested several large ceremonial drums used during worship services. Picking one up our guide beat out a rhythm that would normally accompany liturgical chanting, or Zema, by the young monks. We’ve noticed that the treasures of the Ethiopian churches are not determined by their monetary value and locked securely away, only to be used on religious holidays, but by their spiritual connection. Precious, irreplaceable, ancient bibles and manuscripts, lovingly worn and torn as they are, continue to be used every day, as they have been for the last nine-hundred-years. It is well worth the effort to visit these remote churches and monasteries. The physical strength required and hardships endured to build these remote churches as a testament of faith continues to be inspiring.

It is well worth the effort to visit these remote churches and monasteries. The physical strength required and hardships endured to build these remote churches as a testament of faith continues to be inspiring.

Often overshadowed in recent decades by its East African neighbors recognized for their safaris, Ethiopia has been known to Western culture for millennia. It was first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, around 1000 BC (3,000 years ago!), when the Queen of Sheba, hearing of “Solomon’s great wisdom and the glory of his kingdom,” journeyed from Ethiopia with a caravan of treasure as tribute. Unbeknownst to Solomon their union produced a son, Menilek, (meaning son of the wise man). Years later, wearing a signet ring given to him by his mother, Menilek visited Jerusalem to meet Solomon and stayed for several years to study Hebrew. When his son desired to return home, Solomon gifted the Ark of the Covenant to Menilek for safe keeping in Ethiopia, and to this day it is said to reside in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, in Aksum, where only a select few of the Ethiopian Orthodox church can see it.

Often overshadowed in recent decades by its East African neighbors recognized for their safaris, Ethiopia has been known to Western culture for millennia. It was first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, around 1000 BC (3,000 years ago!), when the Queen of Sheba, hearing of “Solomon’s great wisdom and the glory of his kingdom,” journeyed from Ethiopia with a caravan of treasure as tribute. Unbeknownst to Solomon their union produced a son, Menilek, (meaning son of the wise man). Years later, wearing a signet ring given to him by his mother, Menilek visited Jerusalem to meet Solomon and stayed for several years to study Hebrew. When his son desired to return home, Solomon gifted the Ark of the Covenant to Menilek for safe keeping in Ethiopia, and to this day it is said to reside in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, in Aksum, where only a select few of the Ethiopian Orthodox church can see it.

With the Ethiopian Orthodox Church having a site in Jerusalem since the sixth century, Ethiopian pilgrimages to the Holy Land, which took six months, were common until the route was blocked by Muslim conquests in 1100s and the journey became too hazardous. As it became surrounded further by Muslim territories, the country sank into isolation from Europe. Ethiopia’s early history and its connection to Judaism and Christianity is a twisting tale, like caravan tracks across the desert, meeting then disappearing behind sand dunes, the story buried by the blowing sands of time.

With the Ethiopian Orthodox Church having a site in Jerusalem since the sixth century, Ethiopian pilgrimages to the Holy Land, which took six months, were common until the route was blocked by Muslim conquests in 1100s and the journey became too hazardous. As it became surrounded further by Muslim territories, the country sank into isolation from Europe. Ethiopia’s early history and its connection to Judaism and Christianity is a twisting tale, like caravan tracks across the desert, meeting then disappearing behind sand dunes, the story buried by the blowing sands of time. Distraught by this, King Lalibela commissioned eleven architecturally perfect churches, to be hewn from solid rock, to serve as a New Jerusalem complete with a River Jordan for pilgrims to visit. He based the designs on memories of holy sites from his own pilgrimage to the Holy Land as a young man.

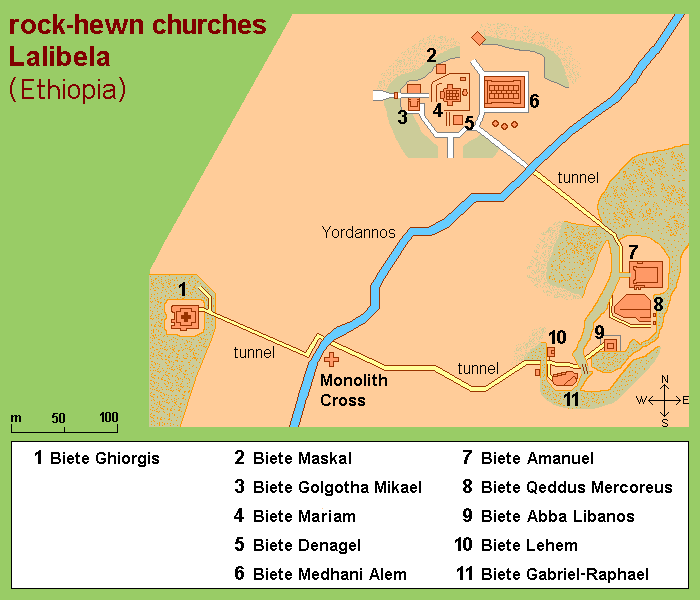

Distraught by this, King Lalibela commissioned eleven architecturally perfect churches, to be hewn from solid rock, to serve as a New Jerusalem complete with a River Jordan for pilgrims to visit. He based the designs on memories of holy sites from his own pilgrimage to the Holy Land as a young man. Considering the limited availability of tools in the 1100s, I can’t imagine what a daunting task this must have been. I’m sure the chief architect said, “you have to be kidding.” It’s believed that 40,000 men, assisted by angels at night, labored for 24 years to create this testament to their faith. Masons outlined the shape of these churches on top of monolithic rocks, then excavated straight down forty feet to create a courtyard around this solid block. Doors would then be chiseled into the block and the creation of the church would continue from the inside, often in near total darkness.

Considering the limited availability of tools in the 1100s, I can’t imagine what a daunting task this must have been. I’m sure the chief architect said, “you have to be kidding.” It’s believed that 40,000 men, assisted by angels at night, labored for 24 years to create this testament to their faith. Masons outlined the shape of these churches on top of monolithic rocks, then excavated straight down forty feet to create a courtyard around this solid block. Doors would then be chiseled into the block and the creation of the church would continue from the inside, often in near total darkness.

Women worshippers traditionally enter through a separate door and pray apart from the men. Inside, thirty-eight stone columns form four aisles and support a stone ceiling that soars overhead. After walking for days or weeks to reach Lalibela, often fasting the entire time, the journey ends here for many pilgrims, in hopes of receiving a blessing or cure from touching the Lalibela Cross and offering prayers.

Women worshippers traditionally enter through a separate door and pray apart from the men. Inside, thirty-eight stone columns form four aisles and support a stone ceiling that soars overhead. After walking for days or weeks to reach Lalibela, often fasting the entire time, the journey ends here for many pilgrims, in hopes of receiving a blessing or cure from touching the Lalibela Cross and offering prayers.

The next morning, we completed our tour of the cluster of the southern of the rock churches: Beta Emmanuel (Church of Emmanuel), Beta Abba Libanos (Church of Father Libanos), Beta Merkurios (Church of Mercurius) and Beta Gabriel and Beta Rafa’el (the twin churches of Gabriel and Raphael.)

The next morning, we completed our tour of the cluster of the southern of the rock churches: Beta Emmanuel (Church of Emmanuel), Beta Abba Libanos (Church of Father Libanos), Beta Merkurios (Church of Mercurius) and Beta Gabriel and Beta Rafa’el (the twin churches of Gabriel and Raphael.)

It’s important to remember that this is not a museum with ancient artifacts and manuscripts in glass cases, but an active holy site where the ancient manuscripts are still used daily, and it is home to a large community of priests and nuns. It has been a destination for Ethiopian Orthodox pilgrims in the northern highlands (elevation 8,200’) for the last 900 years and continues to be visited by tens of thousands of pilgrims annually.

It’s important to remember that this is not a museum with ancient artifacts and manuscripts in glass cases, but an active holy site where the ancient manuscripts are still used daily, and it is home to a large community of priests and nuns. It has been a destination for Ethiopian Orthodox pilgrims in the northern highlands (elevation 8,200’) for the last 900 years and continues to be visited by tens of thousands of pilgrims annually. Leaving the churches behind, we walked through an area of ancient two story, round houses called Lasta Tukuls, or bee huts, built from local, quarried red stone. Abandoned now for preservation, they looked sturdy, their stone construction distinctive from the other homes in the area that use an adobe method.

Leaving the churches behind, we walked through an area of ancient two story, round houses called Lasta Tukuls, or bee huts, built from local, quarried red stone. Abandoned now for preservation, they looked sturdy, their stone construction distinctive from the other homes in the area that use an adobe method. Today roughly 100,000 foreign tourists, in addition to Ethiopian pilgrims, visit Lalibela annually, a far cry from its near obscurity 140 years ago. Located four hundred miles from Addis Ababa, it is still far enough off the usual tourist circuits to make it a unique and inspiring destination.

Today roughly 100,000 foreign tourists, in addition to Ethiopian pilgrims, visit Lalibela annually, a far cry from its near obscurity 140 years ago. Located four hundred miles from Addis Ababa, it is still far enough off the usual tourist circuits to make it a unique and inspiring destination.

The area in the northern part of the Greater Rift Valley, known today as the Omo Valley region of Ethiopia, has been at the crossroads of humankind for many millennia. In 1967 Dr. Leaky discovered fossil bone evidence, recently re-dated by scientists to be 195,000 years old, of early Homo sapiens near Kibish, Ethiopia, several miles west of the Omo River near where the borders of Sudan, Kenya and Ethiopia meet. The first migrations of early man out of Africa occurred 60,000 years ago as they followed the Omo River north through the Great Rift Valley to the Red Sea. At its narrowest point, where it meets the Gulf of Aden, they crossed to continue their migration through Arabia and eventually into Europe and Asia. The region was once rich with African wildlife, and Arab towns along the northern East African coast of Somalia and Kenyan were sending hunting parties into the interior for elephant ivory, rhino horn and unfortunately slaves since around AD 1000.

The area in the northern part of the Greater Rift Valley, known today as the Omo Valley region of Ethiopia, has been at the crossroads of humankind for many millennia. In 1967 Dr. Leaky discovered fossil bone evidence, recently re-dated by scientists to be 195,000 years old, of early Homo sapiens near Kibish, Ethiopia, several miles west of the Omo River near where the borders of Sudan, Kenya and Ethiopia meet. The first migrations of early man out of Africa occurred 60,000 years ago as they followed the Omo River north through the Great Rift Valley to the Red Sea. At its narrowest point, where it meets the Gulf of Aden, they crossed to continue their migration through Arabia and eventually into Europe and Asia. The region was once rich with African wildlife, and Arab towns along the northern East African coast of Somalia and Kenyan were sending hunting parties into the interior for elephant ivory, rhino horn and unfortunately slaves since around AD 1000.

Things change, but the proud peoples that live in the Omo Valley are trying to retain their way of life amidst external influences they can’t control, as tourists and construction crews course across their territory. Tempers flare when trucks and buses carrying supplies and workers to the agricultural plantations strike and kill cattle. Drivers are required to stop and immediately pay the herder for his loss, but many never do. Consequently, the local tribe will block the road and demand payment until the issue is resolved.

Things change, but the proud peoples that live in the Omo Valley are trying to retain their way of life amidst external influences they can’t control, as tourists and construction crews course across their territory. Tempers flare when trucks and buses carrying supplies and workers to the agricultural plantations strike and kill cattle. Drivers are required to stop and immediately pay the herder for his loss, but many never do. Consequently, the local tribe will block the road and demand payment until the issue is resolved. A good night’s sleep at the

A good night’s sleep at the

The 2019 rainy season was good; unfortunately, this is often not the case. There was no water infrastructure in most of the small towns and villages we passed through, forcing folks to gather water from local streams and rivers.

The 2019 rainy season was good; unfortunately, this is often not the case. There was no water infrastructure in most of the small towns and villages we passed through, forcing folks to gather water from local streams and rivers. It was a constant sight: women carrying yellow water jugs along the side of the road back to their homes, or if they could afford it, having it delivered by donkey cart. The terrain varied tremendously, with full rivers on one side of a mountain range and dry on the other side. These conditions forced people to dig into the riverbed in search of water.

It was a constant sight: women carrying yellow water jugs along the side of the road back to their homes, or if they could afford it, having it delivered by donkey cart. The terrain varied tremendously, with full rivers on one side of a mountain range and dry on the other side. These conditions forced people to dig into the riverbed in search of water.

Since Ethiopia is close to the equator, the daylight hours do not vary seasonally. The sun rises quickly in the morning and seems to drop from the sky at the end of the day. By the time we reached the

Since Ethiopia is close to the equator, the daylight hours do not vary seasonally. The sun rises quickly in the morning and seems to drop from the sky at the end of the day. By the time we reached the  At breakfast we watched thick-billed ravens in aerial combat as they rode the thermals just off the restaurant’s terrace. Nearby a staff member stood ready to chase away baboons if they got too close to the customers’ tables.

At breakfast we watched thick-billed ravens in aerial combat as they rode the thermals just off the restaurant’s terrace. Nearby a staff member stood ready to chase away baboons if they got too close to the customers’ tables.

As we entered the village, compounds ringed with woven rattan walls held back tall Enset plants, better known as false banana, also called the “tree against hunger.” This plant is an important staple that is drought resistant and can be harvested year-round. Starch from the plant is scraped from its fibers and fermented in the ground for three months or longer and used to make kocho, a type of flat bread.

As we entered the village, compounds ringed with woven rattan walls held back tall Enset plants, better known as false banana, also called the “tree against hunger.” This plant is an important staple that is drought resistant and can be harvested year-round. Starch from the plant is scraped from its fibers and fermented in the ground for three months or longer and used to make kocho, a type of flat bread.  Fibers from the plant are used to make rope or coffee bean bags, and the leaves are fed to farm animals. We arrived on market day, and an entire hillside about the size of three football fields was covered with activity. From a distance it looked like an animated impressionistic painting, with undulating dots of color dancing under a blue sky.

Fibers from the plant are used to make rope or coffee bean bags, and the leaves are fed to farm animals. We arrived on market day, and an entire hillside about the size of three football fields was covered with activity. From a distance it looked like an animated impressionistic painting, with undulating dots of color dancing under a blue sky.  Sellers of charcoal, sugarcane, vegetables, and a multitude of other goods all had their wares spread out on cloths covering the ground. Men played foosball or ping-pong under the few shade trees that ringed the field.

Sellers of charcoal, sugarcane, vegetables, and a multitude of other goods all had their wares spread out on cloths covering the ground. Men played foosball or ping-pong under the few shade trees that ringed the field.

Men of the Dorze tribe traditionally do the weaving, while the women are responsible for spinning the cotton that the family grows and uses. The colorful textiles they create are highly prized all over the country.

Men of the Dorze tribe traditionally do the weaving, while the women are responsible for spinning the cotton that the family grows and uses. The colorful textiles they create are highly prized all over the country. Back in Arba Minch we stopped at the Lemlem restaurant for a lunch of local lake fish before checking out the crocodiles on Chamo Lake. The lightly fried fish were served whole, while the sides were scored into squares which we picked off with our fingers. It was delicious. Another side of the restaurant served freshly butchered, grilled meat.

Back in Arba Minch we stopped at the Lemlem restaurant for a lunch of local lake fish before checking out the crocodiles on Chamo Lake. The lightly fried fish were served whole, while the sides were scored into squares which we picked off with our fingers. It was delicious. Another side of the restaurant served freshly butchered, grilled meat.

“Sorry for the late pick-up, but the road was full of tuk-tuks carrying families to the university stadium up the street for a graduation ceremony,” Ephrem offered as he bundled us into the Land Cruiser and handed us large bottles of water. “It’s hot where we are going today.”

“Sorry for the late pick-up, but the road was full of tuk-tuks carrying families to the university stadium up the street for a graduation ceremony,” Ephrem offered as he bundled us into the Land Cruiser and handed us large bottles of water. “It’s hot where we are going today.”

We trailed a young Borena girl herding a small group of cattle down a slowly inclined, dusty trench deeper into the earth. It was impossible to avoid cow patties as we steered clear of an exiting herd. Thirty feet below the surface, the trench ended in a bowl shape with a water trough where cattle were drinking. Rhythmic voices emerged from a shallow cave behind the trough. Climbing worn stone steps, we came to a narrow landing above the trough,

We trailed a young Borena girl herding a small group of cattle down a slowly inclined, dusty trench deeper into the earth. It was impossible to avoid cow patties as we steered clear of an exiting herd. Thirty feet below the surface, the trench ended in a bowl shape with a water trough where cattle were drinking. Rhythmic voices emerged from a shallow cave behind the trough. Climbing worn stone steps, we came to a narrow landing above the trough,

A short drive away, our last stop of the day was a well-kept Borena village surrounded by an ochre landscape under a perfect blue sky. Women do the heavy lifting in the villages, building the huts, tending children and crops, and spending a substantial amount of time foraging for firewood and gathering water from far off sources. While the men spend their days moving their cattle across different grazing lands.

A short drive away, our last stop of the day was a well-kept Borena village surrounded by an ochre landscape under a perfect blue sky. Women do the heavy lifting in the villages, building the huts, tending children and crops, and spending a substantial amount of time foraging for firewood and gathering water from far off sources. While the men spend their days moving their cattle across different grazing lands. Women rule their homes and determine who can enter, even prohibiting spouses. “If her husband comes back and finds another man’s spear stuck into the ground outside her house, he cannot go in,” our guide conveyed.

Women rule their homes and determine who can enter, even prohibiting spouses. “If her husband comes back and finds another man’s spear stuck into the ground outside her house, he cannot go in,” our guide conveyed.