One of the things we enjoy most about traveling is picking the brains of folks we’ve had the pleasure of meeting throughout our journeys. Whether it’s a tip from a car rental agent about an isolated restaurant in the Azores or from a young Italian attorney who shared her love of Cadiz, Spain, with us, we try to follow through. Sometimes acting immediately, but mostly tucking the tips away into the deep recesses of our minds to consider in the future.

When the same question is asked of us about the best places to see in the United States, Albuquerque, Santa Fe and Toas in New Mexico immediately top our list as the most unique destination in the USA. Maybe I’m a little cynical with an over-simplified view that the United States is mostly a homogenized mass of sameness that spans 3000 miles from the Atlantic to Pacific, mostly sharing the same landscapes, urban architecture, and strip malls with the same ubiquitous retailers – Home Depot, Starbucks, Panera, Pizza Hut and McDonalds – from coast to coast. Yes, the same is true, though to a much smaller degree, of the urban sprawl that surrounds Albuquerque. Though here you’ll find Blake’s Lotaburger, frito pies, piñon coffee, frybread-style sopapillas, and pozole (a hominy dish) along with parking lots filled with roasters full of Hatch green chilies every September when the harvest comes in and that wonderful aroma fills the air. We hope these photos and this story pique your interest in New Mexico, an endlessly beautiful, culturally diverse, artistic, and quirky place that is truly the “Land of Enchantment.” And a destination we always enjoy exploring.

Start in the Petroglyph National Monument, then follow Central Ave (Old Rt66), from the original adobe buildings of Old Town, circa 1706, east across town up to the Knob Hill area around the University of New Mexico and beyond to the Tijeras Pueblo Archaeological Site and the beginning of The Turquoise Trail. You will have spanned several millennia from the oldest petroglyphs dating from 2000 BC to the present and a blending of cultures that is refreshing. It’s a remarkable stretch of history for a young country that typically dates itself to the English colonies of Jamestown – 1607, and Plymouth – 1620.

A 2013 archeological excavation in northern New Mexico unearthed stone tools used to butcher a mammoth, and radiocarbon testing dated them to be 36,000 years old. These tools are attributed to some of the first people that migrated across the Bering Sea from Asia, the ancestors of Native Americans. Jump forward 35,000 years and you have pueblo Indians living in settlements along the Rio Grande Valley and across northern New Mexico. Their first contact with Europeans comes with a back story and cast of characters worthy of the best fiction writers.

It starts with orders from the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V (Charles I of Spain) to Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca (from Jerez de la Frontera, near Cadiz, from that great tip earlier) authorizing him to colonize the region between Río Soto la Marina, Mexico, and what is now Tampa, Florida, a distance of 1500 miles. Tragically believing the distance between the two was only 45 miles, Cabeza de Vaca landed north of Tampa in April 1528 with 300 men and forty horses. Unable to rendezvous with their ships, the expedition was doomed. Traveling west across the top of the gulf towards the nearest Spanish settlement of Tampico, Mexico they encountered alligators, venomous snakes, and hostile natives. They were captured, enslaved, beset by disease-bearing mosquitos; they crossed numerous creeks, swamps and rivers. By the time they reached the “Isle of Misfortune,” Galveston, Texas a year later, only 15 remained. They crossed the Rio Grande near El Paso. With the help of friendly tribes, Cabeza de Vaca and three others, Alonso del Castillo, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, and his slave Esteban the Moor survived an eight-year Homeric ordeal, that took them across the Mexican desert to the Pacific Ocean before being reunited in 1536 with their compatriots in Mexico City. The three Spaniards were rewarded with titles and land by the King. Cabeza de Vaca became the Viceroy of Paraguay, gained political enemies and was unjustly tried in Spain and imprisoned in North Africa. It is not known if Esteban the Moor was granted his freedom, but he was not forgotten.

De Vaca and his fellow survivors had returned with legends heard from the Indians they encountered of fabulous riches farther inland. These stories of insurmountable wealth were still fresh in everyone’s minds two years later when Friar Marcos de Niza (from Nice, France) arrived in Mexico City after leading the first groups of Franciscans into Peru with Spanish conquistadors to conquer the Inca civilization. In hope of finding the fabled “Seven Cities of Gold,” a treasure that allegedly rivaled that of the Aztecs and Incas civilizations, the Viceroy of Mexico planned an expedition headed by Friar Marcos de Niza, along with Esteban the Moor who had the most knowledge of the area’s tribes, and their customs. It seems from reading various accounts that Esteban led, and Friar Marcos followed. They both were the first foreigners, a North African slave and a European, to explore the area we now recognize as the American Southwest. This is 27 years before the founding of St. Augustine, in Florida in 1565. Friar Marcos claimed Esteban the Moor was killed near a Zuni pueblo when he reached one of the “cities of gold.” Marcos also claimed to have seen a city larger than Mexico City, with buildings nine stories high glittering on the horizon. Dream, mirage, a pueblo glowing like a sunset – a lie? Wanting to avoid Esteban’s fate, the Friar ventured no further and returned to share his exploits in Mexico City. The lust for gold was consuming and a year later, in 1540, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado led an expedition of 400 hundred soldiers with 1500 native porters and Friar Marcos north again to attain that treasure. And boy was he miffed when they reached the Zuni tribe and found nothing but a “poor pueblo.” Accusing Friar Marcos of lying, he sent him back to Mexico. Coronado’s expedition would stay in the region for two years, traveling in several smaller groups west as far as the Grand Canyon and east into Texas and Kansas. They never discovered gold though they did travel through areas where it would be discovered centuries later. They returned emptyhanded. It would be 53 years before Spaniards ventured north again.

In 1595 King Philip II of Spain chose Don Juan de Oñate to colonize the upper Rio Grande valley. In 1598 he led an expedition north that included 20 Franciscan missionaries, 400 settlers, 129 soldiers, 83 wagons, plus livestock, with the stated mission from the Pope to spread Catholicism. But there was still hope that the evasive “Seven Cities of Gold,” would finally be discovered. Fording the Rio Grande near present day El Paso, he proclaimed all the lands north of the river “for God, the Church, and the Crown.” Life in the new territory under Oñate was severe. Some settlers urged a return to Mexico when silver was not discovered, and Oñate executed the dissenters. Pueblos that refused to share winter food stocks needed for their own survival were brutally suppressed into submission. The Spanish imposed the encomendero on the pueblo tribes. This was a colonial business model that granted conquistadores or ordinary Spaniards the right to free labor and tribute from the indigenous population. In return Nuevo México encomiendas were obligated to “instruct the Indians in the Roman Catholic faith and the rudiments of Spanish civilization.” The free land and free Indian labor promised with the encomendero was also used as a recruiting tool to encourage settlers to venture north from Mexico. The pueblos did not submit willingly; any resistance was forcibly repressed until the Pueblo Revolution in 1680. Four-hundred Spaniards died, including 21 priests, but there were almost 2000 Spanish survivors. Warriors followed the fleeing refugees all the way to El Paso to ensure their expulsion from Indian territory. But by then there were three generations of intermarriage, along with shared ideas, technology and customs.

When the Spanish returned 12 years later, they did not try to reimpose the encomendero, and returning missionaries displayed more tolerance of indigenous religious beliefs. Spain instead sought to enlist the Pueblo tribes as allies to resist French and British empire expansion farther west. The vast area claimed by Coronado and Oñate became part of the United States with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War in 1848. It’s a fascinating multilayered history that continues to contribute to New Mexico’s uniqueness.

But enough about history. Land at the Albuquerque International Sunport, rent a car and hit the road. Head north on Rt25, with the Sandia Mountain Range glowing in the late afternoon light on your right and a spectacular sunset in the west. This sublime experience could be the beginning of a long love affair with the state, as it was for us. The expansive vistas and sky, along with incredible light and dramatic ever-changing weather out here are just awesome, especially if it’s your first time to the Southwest. Fair warning: the state can become addictive with endless ways to satisfy your wanderlust.

The ruins of the old Spanish missions in the Salinas Valley and Mountainair are south of Albuquerque. Route 40 East will take you to the beginning of the Turquoise Trail, a splendid backroad route that gracefully curves, rises and falls through the rugged foothills of the Sandia and Ortiz mountains as it follows NM14 north for 65 miles. Pass through the historic towns of Golden, Madrid, Cerrillos and San Marcos just south of Santa Fe. Follow Route 40 West to see the amazing rock drawings at the Petroglyph National Monument or continue farther to the Zuni Reservation, mentioned earlier.

Veer off Rt25 and head to Jemez Springs where you’ll find, red rock canyons, old logging roads and hot springs. Farther along in the Valles Caldera National Preserve you can see herds of elk grazing in a 13-mile-wide meadow that is now all that remains of a collapsed volcano cone after a massive ancient eruption.

Nearby the 11,000-year-old cliff dwellings carved into the canyon walls of Bandelier National Monument are a must stop. There are plenty of interesting detours and quirky stops to make along the way.

Santa Fe and Toas lie in the mountains farther north of Albuquerque and have been popular destinations with artists and writers since the early 1900s – D.H. Lawrence, Georgia O’Keefe and Ansel Adams and many others enjoyed the vibrant Indian and Hispanic cultures. Today Hollywood stars like Julia Roberts, Val Kilmer, Ted Danson, and Oprah Winfrey have homes in the area.

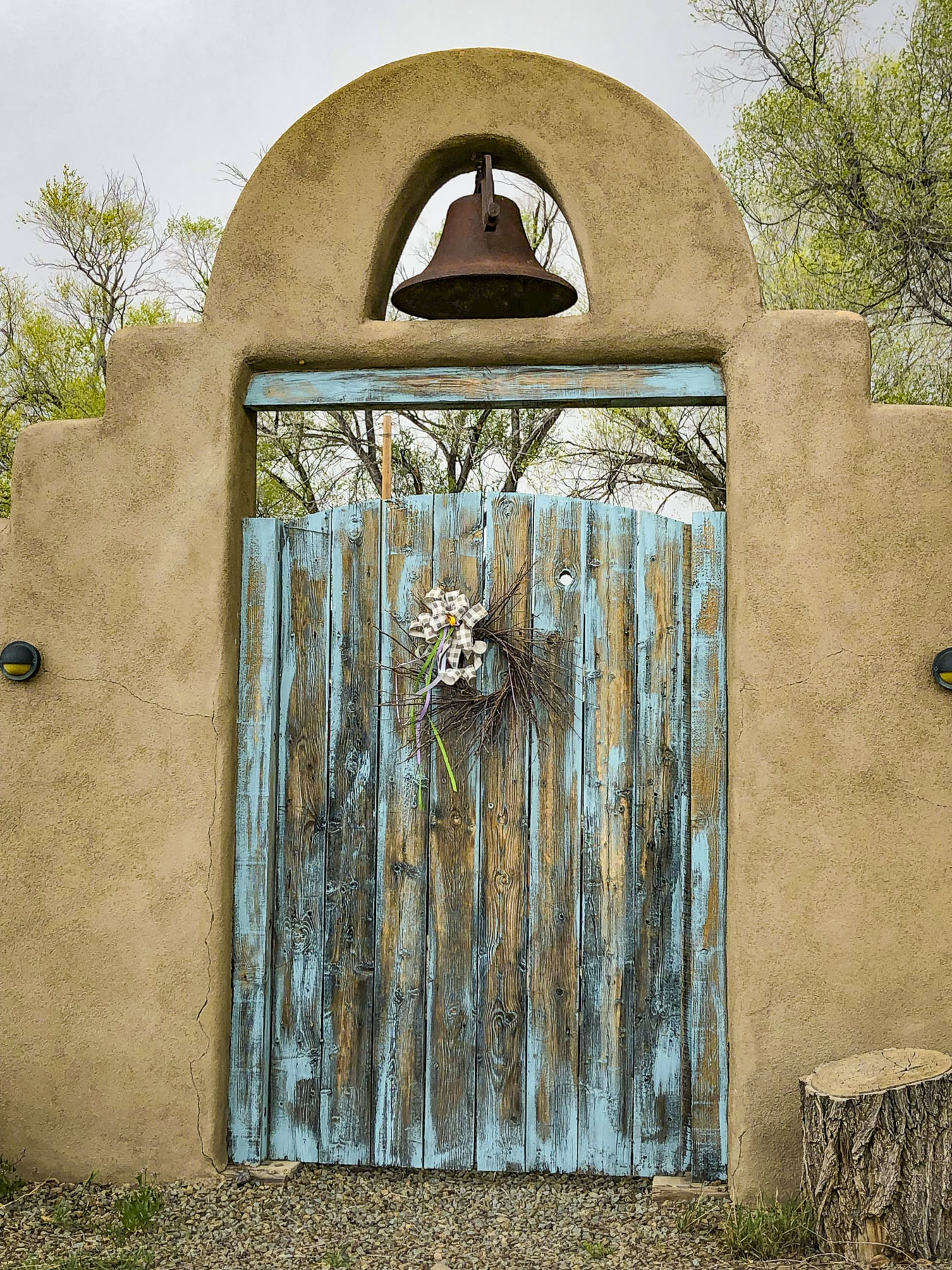

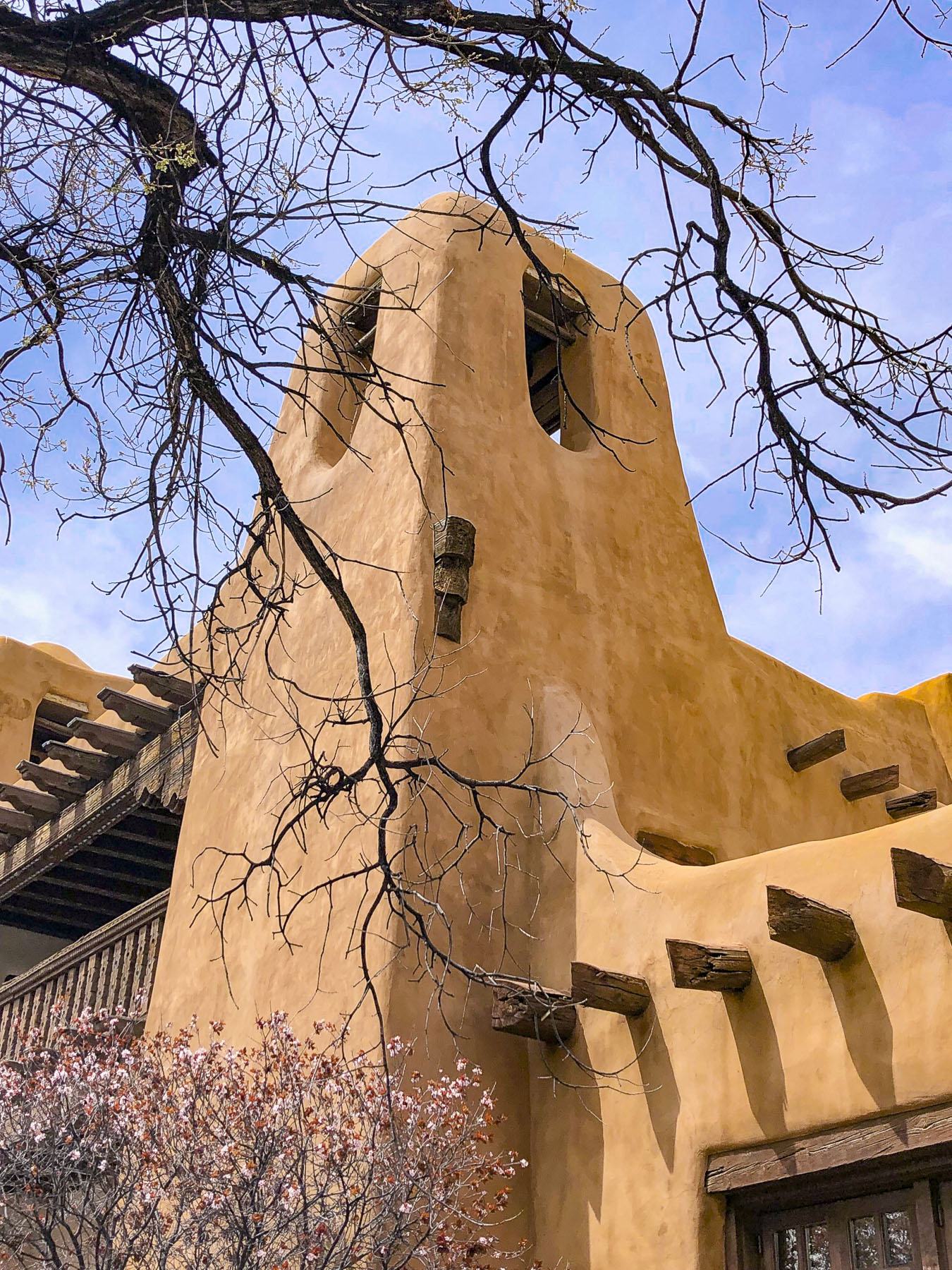

The city retains it early Spanish heritage with historic adobe buildings surrounding Santa Fe Plaza. The Indian market is still held under El Portal in front of the Palace of the Governors, the oldest continually occupied public building in the United States, since its construction in 1610.

The region continues to support artists and craftspeople with numerous galleries, festivals, and fairs. A stretch of 80 art galleries in old adobe buildings along Canyon Road belies its ancient roots as part of El Camino Real, The Royal Road, that ran 1600 miles to Mexico City. Famously Spanish settlers from Mexico introduced chili peppers into the region via this ancient trade route.

The landscapes north of Santa Fe continue to be intriguing, with Black Mesa, sacred to Native Americans, and the Puye Cliff Dwellings which run along the base of a mesa for over a mile. Stairs and paths cut into the cliff face led to adobe structures atop the mesa’s plateau. East of Espanola, the Santuario de Chimayo, built in 1816, still attracts pilgrims seeking miraculous cures from its “healing dirt.”

Heading into the mountains of northern New Mexico, the durability and sustainability of well-maintained adobe structures are evident in the elegant San Francisco de Asis Catholic Mission Church in Rancho de Taos, which dates from 1772.

Impressive Taos Pueblo, a multi-storied residential complex, has been continually occupied since its construction in the 1400s. Today nearly 150 people continue to live traditionally in the pueblo, as their ancestors did, without running water or electricity.

Nearby the Rio Grande River Gorge fractures the earth like a lightning bolt. The view from the center of the bridge looking down into the chasm is magnificent and terrifying. Farther north as the river rises from the gorge it has a totally different character as it meanders through the high desert.

While this far north, it’s worth the effort to visit the Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve, located just across the state line in southern Colorado.

Over many thousands of years, sands blown across the high desert plains accumulated at the base of the Rocky Mountains here to form the tallest dunes in North America.

Wave when you see us!

Till next time, Craig & Donna