Often overshadowed in recent decades by its East African neighbors recognized for their safaris, Ethiopia has been known to Western culture for millennia. It was first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, around 1000 BC (3,000 years ago!), when the Queen of Sheba, hearing of “Solomon’s great wisdom and the glory of his kingdom,” journeyed from Ethiopia with a caravan of treasure as tribute. Unbeknownst to Solomon their union produced a son, Menilek, (meaning son of the wise man). Years later, wearing a signet ring given to him by his mother, Menilek visited Jerusalem to meet Solomon and stayed for several years to study Hebrew. When his son desired to return home, Solomon gifted the Ark of the Covenant to Menilek for safe keeping in Ethiopia, and to this day it is said to reside in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, in Aksum, where only a select few of the Ethiopian Orthodox church can see it.

Often overshadowed in recent decades by its East African neighbors recognized for their safaris, Ethiopia has been known to Western culture for millennia. It was first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, around 1000 BC (3,000 years ago!), when the Queen of Sheba, hearing of “Solomon’s great wisdom and the glory of his kingdom,” journeyed from Ethiopia with a caravan of treasure as tribute. Unbeknownst to Solomon their union produced a son, Menilek, (meaning son of the wise man). Years later, wearing a signet ring given to him by his mother, Menilek visited Jerusalem to meet Solomon and stayed for several years to study Hebrew. When his son desired to return home, Solomon gifted the Ark of the Covenant to Menilek for safe keeping in Ethiopia, and to this day it is said to reside in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, in Aksum, where only a select few of the Ethiopian Orthodox church can see it. The story of the lost tribe of Israel or the Beta Israel (meaning House of Israel) begins with the 12,000 Israelites that Solomon sent to Ethiopia to help Menilek rule following biblical laws. According to legend, Menelik I founded the Solomonic dynasty that ruled Ethiopia with few interruptions for close to three thousand years. This ended 225 generations later, with the deposition of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974.

The story of the lost tribe of Israel or the Beta Israel (meaning House of Israel) begins with the 12,000 Israelites that Solomon sent to Ethiopia to help Menilek rule following biblical laws. According to legend, Menelik I founded the Solomonic dynasty that ruled Ethiopia with few interruptions for close to three thousand years. This ended 225 generations later, with the deposition of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974. Blasphemy, I know, but let’s not forget the Hollywood legend with Indiana Jones rescuing the arc from the Nazis, only to have it unceremoniously stored in an underground warehouse in the Nevada desert. That is an aside, but as the writer I’m allowed to digress.

Blasphemy, I know, but let’s not forget the Hollywood legend with Indiana Jones rescuing the arc from the Nazis, only to have it unceremoniously stored in an underground warehouse in the Nevada desert. That is an aside, but as the writer I’m allowed to digress. Around the same time that Ethiopia appears in the Hebrew Bible, the Greek writer Homer mentioned “Aethiopia” five times in the The Iliad and The Odyssey. In the Histories written by Herodotus (440 BC,) the author describes traveling up the Nile River to the territory of “Aethiopia” which began at Elephantine, modern Aswan.

Around the same time that Ethiopia appears in the Hebrew Bible, the Greek writer Homer mentioned “Aethiopia” five times in the The Iliad and The Odyssey. In the Histories written by Herodotus (440 BC,) the author describes traveling up the Nile River to the territory of “Aethiopia” which began at Elephantine, modern Aswan.

Ethiopian tradition credits the introduction of Christianity to an Ethiopian eunuch in 34 AD, who was baptized by Philip the Apostle. (Acts 8:26-39) He then preached near the palace in Aksum after returning from Israel.

Ethiopian ports on the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden were important stops along the trade route that brought spices from India, along with ivory and exotic animals from Africa to the Roman Empire. In the 4th century AD, Ethiopia’s first Christian king, Ezana of Aksum, sent ambassadors to Constantinople, a newly Christian Byzantine Empire, setting the stage for debates about which country – Armenia, Ethiopia (330AD) or Byzantium – was the first Christian state. Archaeologists point to Ethiopian coins minted in the 4th century bearing a cross and Ezana’s profile as solid proof.

After Ezana’s declaration of Ethiopia as a Christian country, civil war broke out between the Christian and Jewish populations, resulting in the creation of a separate Beta Israel kingdom in the Semien Mountains around Gondar that lasted from the 4th century to 1632.  With the Ethiopian Orthodox Church having a site in Jerusalem since the sixth century, Ethiopian pilgrimages to the Holy Land, which took six months, were common until the route was blocked by Muslim conquests in 1100s and the journey became too hazardous. As it became surrounded further by Muslim territories, the country sank into isolation from Europe. Ethiopia’s early history and its connection to Judaism and Christianity is a twisting tale, like caravan tracks across the desert, meeting then disappearing behind sand dunes, the story buried by the blowing sands of time.

With the Ethiopian Orthodox Church having a site in Jerusalem since the sixth century, Ethiopian pilgrimages to the Holy Land, which took six months, were common until the route was blocked by Muslim conquests in 1100s and the journey became too hazardous. As it became surrounded further by Muslim territories, the country sank into isolation from Europe. Ethiopia’s early history and its connection to Judaism and Christianity is a twisting tale, like caravan tracks across the desert, meeting then disappearing behind sand dunes, the story buried by the blowing sands of time. Distraught by this, King Lalibela commissioned eleven architecturally perfect churches, to be hewn from solid rock, to serve as a New Jerusalem complete with a River Jordan for pilgrims to visit. He based the designs on memories of holy sites from his own pilgrimage to the Holy Land as a young man.

Distraught by this, King Lalibela commissioned eleven architecturally perfect churches, to be hewn from solid rock, to serve as a New Jerusalem complete with a River Jordan for pilgrims to visit. He based the designs on memories of holy sites from his own pilgrimage to the Holy Land as a young man. Considering the limited availability of tools in the 1100s, I can’t imagine what a daunting task this must have been. I’m sure the chief architect said, “you have to be kidding.” It’s believed that 40,000 men, assisted by angels at night, labored for 24 years to create this testament to their faith. Masons outlined the shape of these churches on top of monolithic rocks, then excavated straight down forty feet to create a courtyard around this solid block. Doors would then be chiseled into the block and the creation of the church would continue from the inside, often in near total darkness.

Considering the limited availability of tools in the 1100s, I can’t imagine what a daunting task this must have been. I’m sure the chief architect said, “you have to be kidding.” It’s believed that 40,000 men, assisted by angels at night, labored for 24 years to create this testament to their faith. Masons outlined the shape of these churches on top of monolithic rocks, then excavated straight down forty feet to create a courtyard around this solid block. Doors would then be chiseled into the block and the creation of the church would continue from the inside, often in near total darkness.

European contact with Ethiopia was sporadic over these centuries, until the Portuguese circumnavigated the African continent in the late 1400s and began to establish trading ports along the East African coast. Early in the 1500s the first European to visit the churches of Lalibela was Francisco Alvares, a Portuguese priest assigned to the Ethiopian court as an emissary. He declared them a “wonder of the world,” penning “I weary of writing more about these buildings, because it seems to me that I shall not be believed if I write more… I swear by God, in Whose power I am, that all I have written is the truth.” It would be almost four hundred years before the next European, Gerhard Rohlfs, a German cartographer, laid eyes on them in the late 1860s.

The magnificence of this accomplishment didn’t reveal itself subtly, like a vision slowly rising from the horizon, but smacked us in the face with a WOW! as we emerged single file from a deep and narrow moss-covered trench dug from the reddish volcanic rock.

“The setting was intentionally designed to give the pilgrims a ‘spiritual journey’ of ascending to heaven as the sky and the 40 ft tall façade of Bete Medhane Alem (Church of the Savior of the World), burst forth before them after exiting the darkness,” our guide explained. The largest rock church in Lalibela and in the world is also significant because it’s believed “The hand of God touched one of its columns in a dream King Lalibela had,” our guide Girma Derbi shared as he explained the church’s columned façade that looks like it was inspired by the Parthenon.

Pilgrims in long white robes made their way through three doors that in all Ethiopian Orthodox churches face west, north and south. The nave is always on the east side of the building. “All visitors must remove their shoes before entering the church and leave them outside. You don’t have to, but it’s good if you hire a shoe guard to watch them. Unattended shoes have been known to disappear,” our guide advised.

Fatima, an official shoe guard registered with the historic site, accompanied us for the next two days as we explored the churches and passages. This kind woman helped us numerous times as we navigated treacherous footing and steep steps. Our wisdom in hiring her was reinforced when we encountered a tourist sitting shoeless, outside a church, contemplating an uncomfortable walk ahead. Women worshippers traditionally enter through a separate door and pray apart from the men. Inside, thirty-eight stone columns form four aisles and support a stone ceiling that soars overhead. After walking for days or weeks to reach Lalibela, often fasting the entire time, the journey ends here for many pilgrims, in hopes of receiving a blessing or cure from touching the Lalibela Cross and offering prayers.

Women worshippers traditionally enter through a separate door and pray apart from the men. Inside, thirty-eight stone columns form four aisles and support a stone ceiling that soars overhead. After walking for days or weeks to reach Lalibela, often fasting the entire time, the journey ends here for many pilgrims, in hopes of receiving a blessing or cure from touching the Lalibela Cross and offering prayers.

We spent the rest of the day following Orthodox nuns in yellow robes, and pilgrims carrying prayer staffs along narrow interconnecting passages, through tunnels and then portals to the other Northern Churches (churches located north of a stream renamed the Jordan River.) In many churches there are stacks of prayer staffs by the entrance. These are for congregants to lean on, as there are no chairs in the churches and everyone must stand during the long worship services.

Beta Maryam (Church of Mary), Beta Masqal (Church of the Cross), Beta Danagel (Church of the Virgins), Beta Mika’el (Church of Michael), and Beta Golgotha (Church of Golgotha) all share common elements, yet they are all fascinatingly different in their various carved windows, uneven floors covered with carpets, decorated columns, frescoed walls and religious paintings. The high-banked courtyards around the churches contain caves where monks and hermits slept, or became the final resting spot of pilgrims who could go no further, their mummified remains still visible in certain places. The footpaths between churches double as drainage canals in the rainy season to whisk away water to the Jordan River. We ended our day at Beta Giyorgis (Church of St. George). This stunning cross-shaped church was excavated over thirty feet deep into the top of a hill. It is the most widely recognized of the eleven rock churches and was easily viewed from a small bluff adjacent to it, its beautiful orange patina glowing in the afternoon sun.

We ended our day at Beta Giyorgis (Church of St. George). This stunning cross-shaped church was excavated over thirty feet deep into the top of a hill. It is the most widely recognized of the eleven rock churches and was easily viewed from a small bluff adjacent to it, its beautiful orange patina glowing in the afternoon sun.

It has weathered the centuries better than many of the other churches which have had protective coverings suspended above them, to shield the stone structures from deterioration caused by the effects of weather and climate change. The next morning, we completed our tour of the cluster of the southern of the rock churches: Beta Emmanuel (Church of Emmanuel), Beta Abba Libanos (Church of Father Libanos), Beta Merkurios (Church of Mercurius) and Beta Gabriel and Beta Rafa’el (the twin churches of Gabriel and Raphael.)

The next morning, we completed our tour of the cluster of the southern of the rock churches: Beta Emmanuel (Church of Emmanuel), Beta Abba Libanos (Church of Father Libanos), Beta Merkurios (Church of Mercurius) and Beta Gabriel and Beta Rafa’el (the twin churches of Gabriel and Raphael.)

We arrived at Beta Gabriel and Beta Rafa’el after passing through a wide tunnel that lead to a slender bridge across a deep chasm. It was silent outside, but as we opened the door to enter, the sound of chanting male voices filled the air. We were graciously welcomed into a cavernous room filled with men leaning on prayer staffs or raising them in rhythm, as they sang a liturgical chant, or Zema, accompanied by a drumbeat and the clatter of sistrum rattles. This form of worship has been a tradition in the Ethiopian church since the sixth century. To hear their Zema, click here. It’s important to remember that this is not a museum with ancient artifacts and manuscripts in glass cases, but an active holy site where the ancient manuscripts are still used daily, and it is home to a large community of priests and nuns. It has been a destination for Ethiopian Orthodox pilgrims in the northern highlands (elevation 8,200’) for the last 900 years and continues to be visited by tens of thousands of pilgrims annually.

It’s important to remember that this is not a museum with ancient artifacts and manuscripts in glass cases, but an active holy site where the ancient manuscripts are still used daily, and it is home to a large community of priests and nuns. It has been a destination for Ethiopian Orthodox pilgrims in the northern highlands (elevation 8,200’) for the last 900 years and continues to be visited by tens of thousands of pilgrims annually. Leaving the churches behind, we walked through an area of ancient two story, round houses called Lasta Tukuls, or bee huts, built from local, quarried red stone. Abandoned now for preservation, they looked sturdy, their stone construction distinctive from the other homes in the area that use an adobe method.

Leaving the churches behind, we walked through an area of ancient two story, round houses called Lasta Tukuls, or bee huts, built from local, quarried red stone. Abandoned now for preservation, they looked sturdy, their stone construction distinctive from the other homes in the area that use an adobe method. Today roughly 100,000 foreign tourists, in addition to Ethiopian pilgrims, visit Lalibela annually, a far cry from its near obscurity 140 years ago. Located four hundred miles from Addis Ababa, it is still far enough off the usual tourist circuits to make it a unique and inspiring destination.

Today roughly 100,000 foreign tourists, in addition to Ethiopian pilgrims, visit Lalibela annually, a far cry from its near obscurity 140 years ago. Located four hundred miles from Addis Ababa, it is still far enough off the usual tourist circuits to make it a unique and inspiring destination.

Our visit to Lalibela was the fulfillment of a long-held wish to see these incredible churches, which are an amazing testament to the faith of the Ethiopian people. The altitude challenged us, and it wasn’t always easy to reach the churches themselves, navigating narrow alleys with uneven footing and eroded steps, but we are so glad we persevered. It was a once in a lifetime experience that we will never forget.

Till next time, Craig & Donna

After our last apartment in the “Mother City,” on Bree Street, we moved to the Sea Point neighborhood and as its name suggests, it hugs the coastline under Signal Hill and Lion’s Head Mountain. Finding the ideal apartment for our last 30 days in Cape Town required a bit of detective work on our part though. One of the draw backs of using Airbnb is that it does not provide the specific address of a property until you actually book it. So, while the interior photos of a listing might be charming, its exact location could be anywhere within a five-block radius of a dot on the map, unless the host gives hints in the apartment description.

After our last apartment in the “Mother City,” on Bree Street, we moved to the Sea Point neighborhood and as its name suggests, it hugs the coastline under Signal Hill and Lion’s Head Mountain. Finding the ideal apartment for our last 30 days in Cape Town required a bit of detective work on our part though. One of the draw backs of using Airbnb is that it does not provide the specific address of a property until you actually book it. So, while the interior photos of a listing might be charming, its exact location could be anywhere within a five-block radius of a dot on the map, unless the host gives hints in the apartment description. In Sea Point this could mean on the water or nowhere near it. But with a little sleuthing regarding our final three choices, we were able to determine which one was right on the waterfront. Our reconnaissance of the neighborhood paid off and we booked a sixth-floor one-bedroom apartment with a terrace, that had an ocean view for dramatic sunsets and inland views of the paragliders launching from Signal Hill.

In Sea Point this could mean on the water or nowhere near it. But with a little sleuthing regarding our final three choices, we were able to determine which one was right on the waterfront. Our reconnaissance of the neighborhood paid off and we booked a sixth-floor one-bedroom apartment with a terrace, that had an ocean view for dramatic sunsets and inland views of the paragliders launching from Signal Hill.  It was the perfect location across from the Sea Point promenade. The lively Mojo Market, with numerous food stalls and live music seven nights a week, was just around the corner. Here we enjoyed the best fresh oysters and mussels in sauce at The Mussel Monger & Oyster Bar while sipping South African wine or local craft beers as the nightly band played.

It was the perfect location across from the Sea Point promenade. The lively Mojo Market, with numerous food stalls and live music seven nights a week, was just around the corner. Here we enjoyed the best fresh oysters and mussels in sauce at The Mussel Monger & Oyster Bar while sipping South African wine or local craft beers as the nightly band played. It’s actually possible to walk along the promenade from the V&A Waterfront all the way to the Camps Bay Beach. It’s a little over six miles in length, but it’s a popular stretch of sidewalk, which locals call the Prom.

It’s actually possible to walk along the promenade from the V&A Waterfront all the way to the Camps Bay Beach. It’s a little over six miles in length, but it’s a popular stretch of sidewalk, which locals call the Prom.

Weather permitting, paragliders seemed to launch in rapid succession all day long from Signal Hill, first riding the thermals along the ridge towards Lion’s Head before turning back and gracefully spiraling down over the rooftops of Sea Point to land in a grassy park next to the promenade.

Weather permitting, paragliders seemed to launch in rapid succession all day long from Signal Hill, first riding the thermals along the ridge towards Lion’s Head before turning back and gracefully spiraling down over the rooftops of Sea Point to land in a grassy park next to the promenade. We transitioned easily into our new neighborhood, finding three grocery stores and

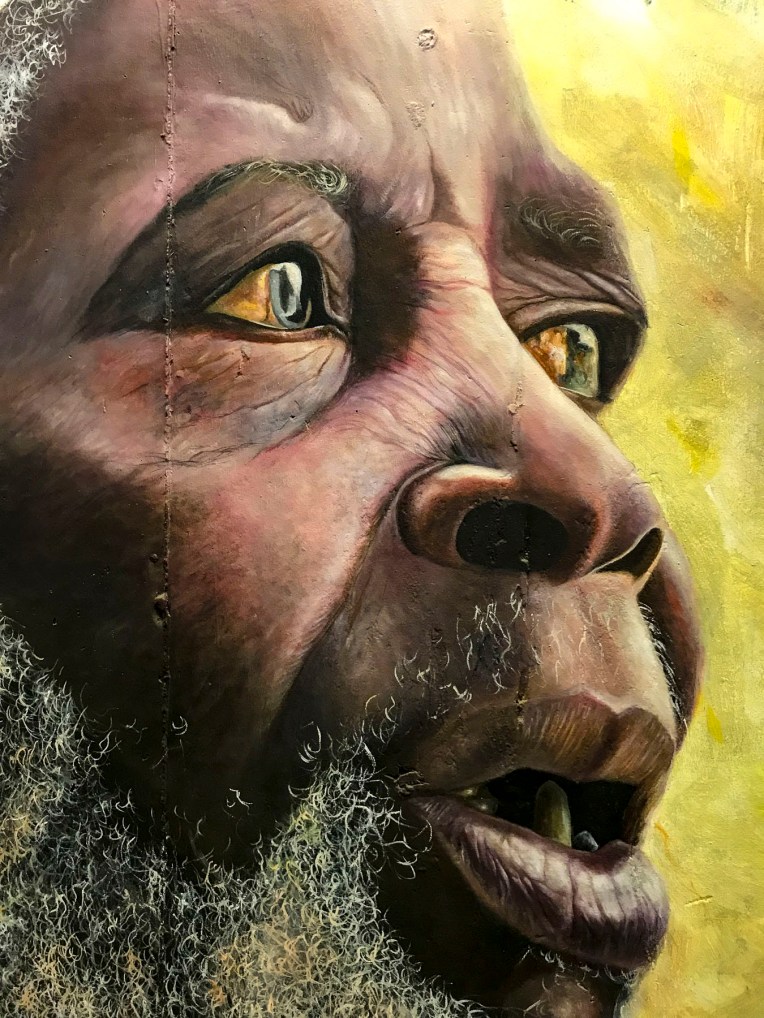

We transitioned easily into our new neighborhood, finding three grocery stores and  Cape Town artists will paint anywhere and the walls of the underground parking garage at the Pick ‘n Pay – Sea Point were the perfect canvases for some incredibly talented street muralists. Sadly, we don’t think enough folks see these hidden works of art.

Cape Town artists will paint anywhere and the walls of the underground parking garage at the Pick ‘n Pay – Sea Point were the perfect canvases for some incredibly talented street muralists. Sadly, we don’t think enough folks see these hidden works of art.

In Hout Bay, time flew by at the

In Hout Bay, time flew by at the

The wind was so strong it made it impossible to hold the camera steady. We soaked in the views as long as we could before the buffeting winds forced our retreat. Sitting outside at the snack bar we were astonished to witness a baboon snatch an ice-cream cone from a young boy and then gobble it up with great delight.

The wind was so strong it made it impossible to hold the camera steady. We soaked in the views as long as we could before the buffeting winds forced our retreat. Sitting outside at the snack bar we were astonished to witness a baboon snatch an ice-cream cone from a young boy and then gobble it up with great delight. We revisited the Simon’s Town area several times, because to see all the spots that interested us required more than one day. The big draw to Simon’s Town was the Boulders Penguin Colony. This is a restricted reserve where visitors must stay on the boardwalk in the viewing areas. Our timing was perfect as penguin chicks had recently hatched and could be seen at the nests snuggling against their parents for warmth. The beach was full of activity, with different groups of penguins doing their best Charlie Chaplin struts into or out of the turquoise waters of the bay.

We revisited the Simon’s Town area several times, because to see all the spots that interested us required more than one day. The big draw to Simon’s Town was the Boulders Penguin Colony. This is a restricted reserve where visitors must stay on the boardwalk in the viewing areas. Our timing was perfect as penguin chicks had recently hatched and could be seen at the nests snuggling against their parents for warmth. The beach was full of activity, with different groups of penguins doing their best Charlie Chaplin struts into or out of the turquoise waters of the bay.

One morning in late July we opted to try a whale watching tour again, this time from the Simon’s Town waterfront, hoping to see some tail slapping or breaching action that was elusive in Hermanus earlier. Alas, we only viewed one tail slap on this trip. As much as the tour operators want you to believe July is a good month for viewing whales, based on our disappointing experiences we’d suggest waiting till later in August or September for more certainty when larger whale pods return to the waters of False Bay. But it was a smooth day at sea, cruising along a dramatic coast and we did get to view a large colony of sea lions on some offshore rocks.

One morning in late July we opted to try a whale watching tour again, this time from the Simon’s Town waterfront, hoping to see some tail slapping or breaching action that was elusive in Hermanus earlier. Alas, we only viewed one tail slap on this trip. As much as the tour operators want you to believe July is a good month for viewing whales, based on our disappointing experiences we’d suggest waiting till later in August or September for more certainty when larger whale pods return to the waters of False Bay. But it was a smooth day at sea, cruising along a dramatic coast and we did get to view a large colony of sea lions on some offshore rocks.

Once outside of Cape Town the R27 cut a desolate track through a rolling landscape of open fynbos with scarcely a tree to be seen. Every so often the head of an antelope or ostrich could be seen emerging above the bushes on either side of the road. The heather clad landscape eventually gave way to pastureland speckled with sheep and wheat fields.

Once outside of Cape Town the R27 cut a desolate track through a rolling landscape of open fynbos with scarcely a tree to be seen. Every so often the head of an antelope or ostrich could be seen emerging above the bushes on either side of the road. The heather clad landscape eventually gave way to pastureland speckled with sheep and wheat fields. Paternoster is one of the Western Cape’s oldest fishing villages, dating from the early 1800s, and is said to have gotten its name from Portuguese sailors who evoked the Lord’s Prayer to save themselves from shipwreck off its coast. The area was first explored when Vasco da Gama landed nearby in Helena Bay, in 1497. By then the area had been inhabited by the indigenous Khoisan for thousands of years. Hunter-gatherers, they harvested dune spinach, an local vegetable, from the beaches, and shellfish from the area waters, and they left behind middens that have been estimated to be 3,000-4,000 years old. The harvesting of the ocean’s bounty continues, with fishermen still launching their small boats into the sea from the beach and returning with fish and lobsters. As you pull into the village it’s not unusual to see fishermen selling their day’s catch from five- gallon buckets at the town’s intersections, where they hoist live lobsters aloft and yell “kry hier kreef!”, Afrikaans for “get some lobster here.” Aside from the picturesque whitewashed and thatched roofed fisherman’s cottages along a white sand beach dotted with boulders, there’s not much to this sleepy fishing village, except for some reportedly excellent seafood restaurants that were unfortunately closed the winter day we visited.

Paternoster is one of the Western Cape’s oldest fishing villages, dating from the early 1800s, and is said to have gotten its name from Portuguese sailors who evoked the Lord’s Prayer to save themselves from shipwreck off its coast. The area was first explored when Vasco da Gama landed nearby in Helena Bay, in 1497. By then the area had been inhabited by the indigenous Khoisan for thousands of years. Hunter-gatherers, they harvested dune spinach, an local vegetable, from the beaches, and shellfish from the area waters, and they left behind middens that have been estimated to be 3,000-4,000 years old. The harvesting of the ocean’s bounty continues, with fishermen still launching their small boats into the sea from the beach and returning with fish and lobsters. As you pull into the village it’s not unusual to see fishermen selling their day’s catch from five- gallon buckets at the town’s intersections, where they hoist live lobsters aloft and yell “kry hier kreef!”, Afrikaans for “get some lobster here.” Aside from the picturesque whitewashed and thatched roofed fisherman’s cottages along a white sand beach dotted with boulders, there’s not much to this sleepy fishing village, except for some reportedly excellent seafood restaurants that were unfortunately closed the winter day we visited. A short way out of town we followed a dirt road to the Cape Columbine Lighthouse. Built in 1936, on an outcropping of boulders called Castle Rock, it’s one of the last manned lighthouses in South Africa. “Seniors are free,” the lighthouse keeper, a senior himself, announced, as he pointed us to a set of stairs that eventually led to a very tall, steep wooden ladder. The panoramic view from the top was brilliant and, as expected, breathtaking. Getting down was a little more challenging than getting up. It was a kind of “make it or break every bone in your body if you don’t” situation. We’ve found in our travels around the world that folks in other countries can do all sorts of risky things, that in the states wouldn’t be allowed for safety concerns. Overseas it’s all about being responsible for your own safety. “See you at the bottom,” Donna said as she agilely maneuvered on to the ladder. “One way or another,” I grimaced in response. For me, with a fearful respect for height, it was all about that first step down.

A short way out of town we followed a dirt road to the Cape Columbine Lighthouse. Built in 1936, on an outcropping of boulders called Castle Rock, it’s one of the last manned lighthouses in South Africa. “Seniors are free,” the lighthouse keeper, a senior himself, announced, as he pointed us to a set of stairs that eventually led to a very tall, steep wooden ladder. The panoramic view from the top was brilliant and, as expected, breathtaking. Getting down was a little more challenging than getting up. It was a kind of “make it or break every bone in your body if you don’t” situation. We’ve found in our travels around the world that folks in other countries can do all sorts of risky things, that in the states wouldn’t be allowed for safety concerns. Overseas it’s all about being responsible for your own safety. “See you at the bottom,” Donna said as she agilely maneuvered on to the ladder. “One way or another,” I grimaced in response. For me, with a fearful respect for height, it was all about that first step down.

It’s here that we first noticed the really interesting street murals that could be seen on some of the homes. Not gratuitous bubble-scripted graffiti, but pictorial or political works of art relating to freedom, equality and hope by talented artists that enhanced their surroundings.

It’s here that we first noticed the really interesting street murals that could be seen on some of the homes. Not gratuitous bubble-scripted graffiti, but pictorial or political works of art relating to freedom, equality and hope by talented artists that enhanced their surroundings.

In our exploration of Cape Town, we accidentally and to our delight, came across many wonderful murals while walking or driving about. Behind our apartment on Harrington Street a wonderfully, whimsical mural of a dog dreaming about flying, by Belgian artist

In our exploration of Cape Town, we accidentally and to our delight, came across many wonderful murals while walking or driving about. Behind our apartment on Harrington Street a wonderfully, whimsical mural of a dog dreaming about flying, by Belgian artist  Farther down the street in District 6, across from Charlie’s Bakery, a colorful mural graced the back of a small building in a parking lot, while its front wall featured an understated portrait of Nelson Mandela by

Farther down the street in District 6, across from Charlie’s Bakery, a colorful mural graced the back of a small building in a parking lot, while its front wall featured an understated portrait of Nelson Mandela by  And at the bus station, under the highway, across from the Gardens Shopping Center the dismal gray walls sprang to life with imagery.

And at the bus station, under the highway, across from the Gardens Shopping Center the dismal gray walls sprang to life with imagery.

Turns out the Woodstock and Salt River neighborhoods are ground zero for freedom of expression based on the number of street murals we discovered just by driving around. One seemed to lead to another around the corner.

Turns out the Woodstock and Salt River neighborhoods are ground zero for freedom of expression based on the number of street murals we discovered just by driving around. One seemed to lead to another around the corner.  When we stopped to photograph the mural of the swimming elephant, one of the unofficial parking guards introduced himself as the “curator of street art” and offered to guide us.

When we stopped to photograph the mural of the swimming elephant, one of the unofficial parking guards introduced himself as the “curator of street art” and offered to guide us.

Traveling along Victoria Road in the Salt River district, the large mural of a pangolin, painted by Belgian street artist

Traveling along Victoria Road in the Salt River district, the large mural of a pangolin, painted by Belgian street artist  The festival is sponsored by

The festival is sponsored by

His style is very distinctive, and we recognized many of his works as we traveled around the Cape. Back in town the exterior wall of Surfstore Africa is playfully illustrated with a giraffe wearing sunglasses.

His style is very distinctive, and we recognized many of his works as we traveled around the Cape. Back in town the exterior wall of Surfstore Africa is playfully illustrated with a giraffe wearing sunglasses. Our most unexpected discovery happened at the indoor parking garage of the Pick N Pay grocery store in Sea Point. Here several beautiful portraits were painted on the walls of the driving ramp leading from one level to the next.

Our most unexpected discovery happened at the indoor parking garage of the Pick N Pay grocery store in Sea Point. Here several beautiful portraits were painted on the walls of the driving ramp leading from one level to the next.

Here gale force winds that blow in from Antarctica and colliding warm and cold currents build ferocious waves that can tower to 100 feet high. These seas have claimed over 140 ships since the Portuguese first sailed here in the 1500s. Within sight of the lighthouse, the most recent wreck of a Japanese fishing trawler from 1982 lies on the beach rusting away.

Here gale force winds that blow in from Antarctica and colliding warm and cold currents build ferocious waves that can tower to 100 feet high. These seas have claimed over 140 ships since the Portuguese first sailed here in the 1500s. Within sight of the lighthouse, the most recent wreck of a Japanese fishing trawler from 1982 lies on the beach rusting away. We stayed the night at the

We stayed the night at the

Afterwards we headed toward Wilderness (the town not the idea,) along a route that traversed barren farmlands and coastal pine forests before skirting the coast again at Mossel Bay. We arrived in time to watch the sunset from our balcony at

Afterwards we headed toward Wilderness (the town not the idea,) along a route that traversed barren farmlands and coastal pine forests before skirting the coast again at Mossel Bay. We arrived in time to watch the sunset from our balcony at  Our room was luxurious and larger than several of the apartments we had rented on our round-the-world journey so far. We were hoping the owners, Leane & Deon, would adopt us. On our sunrise walk the next morning we only sighted a few other folks enjoying the quiet of this vast stretch of pristine beach during the winter season. We noted the considerably warmer weather, a result of the Agulhas Current which swoops warm Indian Ocean currents along the bottom of South Africa and wonderfully moderates the temperature.

Our room was luxurious and larger than several of the apartments we had rented on our round-the-world journey so far. We were hoping the owners, Leane & Deon, would adopt us. On our sunrise walk the next morning we only sighted a few other folks enjoying the quiet of this vast stretch of pristine beach during the winter season. We noted the considerably warmer weather, a result of the Agulhas Current which swoops warm Indian Ocean currents along the bottom of South Africa and wonderfully moderates the temperature.  After breakfast we backtracked on N2 to the pullover above the Kaaimans River Railway Bridge. For railroad enthusiasts this was a destination for many years to watch the Outeniqua Choo Tjoe, the last continually operating steam train in Africa, cross the tidal estuary which slowed settlers’ advance along the rugged coast. The line stopped operating in 2006 when landslides destroyed an extensive stretch of track. Today it’s an interesting photo-op.

After breakfast we backtracked on N2 to the pullover above the Kaaimans River Railway Bridge. For railroad enthusiasts this was a destination for many years to watch the Outeniqua Choo Tjoe, the last continually operating steam train in Africa, cross the tidal estuary which slowed settlers’ advance along the rugged coast. The line stopped operating in 2006 when landslides destroyed an extensive stretch of track. Today it’s an interesting photo-op.  Further up the gorge at Map of Africa View Point, raging waters over the eons have eroded a bend in the river to resemble the African continent when viewed from the overlook on the opposite side of the chasm. The sky was empty mid-week, but across the road hundreds of paragliders launch from the grassy slope on the weekends to catch fantastic thermals and awesome views of the coast below.

Further up the gorge at Map of Africa View Point, raging waters over the eons have eroded a bend in the river to resemble the African continent when viewed from the overlook on the opposite side of the chasm. The sky was empty mid-week, but across the road hundreds of paragliders launch from the grassy slope on the weekends to catch fantastic thermals and awesome views of the coast below.

After spending hours rattling along dusty back roads we rejoiced to be on Route 2 again. A little while later we pulled over and enjoyed a late lunch and sunny afternoon on the outdoor deck of the Cruise Café, which overlooked Knysna Bay.

After spending hours rattling along dusty back roads we rejoiced to be on Route 2 again. A little while later we pulled over and enjoyed a late lunch and sunny afternoon on the outdoor deck of the Cruise Café, which overlooked Knysna Bay.  We weren’t yet synched to the rhythm of life outside of Cape Town in the off-season and were surprised to find the restaurants and grocery stores in Plettenberg Bay closed when we arrived. Fortunately, we had a wonderful room with an ocean and lagoon view terrace, right on Lookout Beach, at

We weren’t yet synched to the rhythm of life outside of Cape Town in the off-season and were surprised to find the restaurants and grocery stores in Plettenberg Bay closed when we arrived. Fortunately, we had a wonderful room with an ocean and lagoon view terrace, right on Lookout Beach, at  The sun rose quickly the next morning from behind the Tsitsikamma Mountains, across the bay, filling our room with light. We spent the early morning slowly sipping coffee and savoring the view. Upon checkout we were delighted to find a sparkling clean car. This was a wonderful service the hotel provided for guests, and an easy way for the gardener to earn some extra money.

The sun rose quickly the next morning from behind the Tsitsikamma Mountains, across the bay, filling our room with light. We spent the early morning slowly sipping coffee and savoring the view. Upon checkout we were delighted to find a sparkling clean car. This was a wonderful service the hotel provided for guests, and an easy way for the gardener to earn some extra money. We kept to a strict schedule, and limited our stops for photos today, because we needed to be at

We kept to a strict schedule, and limited our stops for photos today, because we needed to be at  Three guides and three open-sided 4×4 Toyota safari trucks, each capable of seating 16 people, were waiting for their respective groups at the reserve’s headquarters. Wonderfully, it was mid-week in the off-season, and we had Edward, our guide/naturalist, and truck all to ourselves, while the other two trucks left with groups of six each. Schotia’s 4,000 acres of gently rolling hills, bush and forest shelter approximately 2,000 animals from 40 mammal species and its’s amazing how difficult it can be to find them.

Three guides and three open-sided 4×4 Toyota safari trucks, each capable of seating 16 people, were waiting for their respective groups at the reserve’s headquarters. Wonderfully, it was mid-week in the off-season, and we had Edward, our guide/naturalist, and truck all to ourselves, while the other two trucks left with groups of six each. Schotia’s 4,000 acres of gently rolling hills, bush and forest shelter approximately 2,000 animals from 40 mammal species and its’s amazing how difficult it can be to find them.  But that was our goal as we rattled along the rutted paths to a high vantage point within the reserve, that provided distant views of the terrain surrounding us. Scanning the vista with binoculars, Edward was searching for elephants, giraffes, antelopes and zebra. “The animals are constantly on the move. We’re never really sure where they will be,” Edward offered. He seconded with, “There’s clouds of dust being kicked up over there. Can’t tell from here what they are, but let’s go investigate.” And our overlanding began, chasing a cloud of dust that turned out to be a small herd of white faced Blesbok, a stunning antelope species we weren’t familiar with.

But that was our goal as we rattled along the rutted paths to a high vantage point within the reserve, that provided distant views of the terrain surrounding us. Scanning the vista with binoculars, Edward was searching for elephants, giraffes, antelopes and zebra. “The animals are constantly on the move. We’re never really sure where they will be,” Edward offered. He seconded with, “There’s clouds of dust being kicked up over there. Can’t tell from here what they are, but let’s go investigate.” And our overlanding began, chasing a cloud of dust that turned out to be a small herd of white faced Blesbok, a stunning antelope species we weren’t familiar with.

Sightings of impala, kudu, wildebeest, warthogs, cape buffalo, zebra, hippos and crocodiles rounded out the afternoon.

Sightings of impala, kudu, wildebeest, warthogs, cape buffalo, zebra, hippos and crocodiles rounded out the afternoon.

On the way back to the lapa we encountered the hippos we had seen earlier, now grazing far from their waterhole. Large black masses, they were barely visible when out of the headlights.

On the way back to the lapa we encountered the hippos we had seen earlier, now grazing far from their waterhole. Large black masses, they were barely visible when out of the headlights. Glasses of wine and a large, warming fire greeted us when we returned to the lapa for dinner. Inland the temperature fell quickly, and the warmth from the flames felt good.

Glasses of wine and a large, warming fire greeted us when we returned to the lapa for dinner. Inland the temperature fell quickly, and the warmth from the flames felt good. Darkness covered the countryside early in June, the beginning of South Africa’s winter season. Our guide had just lit the oil lamps a few minutes earlier, handed us a walkie-talkie and said, “Use this to call the owner if there’s an emergency, you’re the only folks here tonight.’’ The owner lived somewhere on the other side of this vast reserve. There were no other lights around except for the moon. The bush has a life of its own and sounds totally different in the darkness.

Darkness covered the countryside early in June, the beginning of South Africa’s winter season. Our guide had just lit the oil lamps a few minutes earlier, handed us a walkie-talkie and said, “Use this to call the owner if there’s an emergency, you’re the only folks here tonight.’’ The owner lived somewhere on the other side of this vast reserve. There were no other lights around except for the moon. The bush has a life of its own and sounds totally different in the darkness. We didn’t plan on being the only folks at the game reserve during the middle of the week, but that’s one of the benefits of off-season travel. Following spring-like conditions around the globe, we’ve been able to avoid hot, humid weather and the crowds, while managing to have some wonderful experiences along the way. Tomorrow, Edward would guide us through Addo Elephant National Park.

We didn’t plan on being the only folks at the game reserve during the middle of the week, but that’s one of the benefits of off-season travel. Following spring-like conditions around the globe, we’ve been able to avoid hot, humid weather and the crowds, while managing to have some wonderful experiences along the way. Tomorrow, Edward would guide us through Addo Elephant National Park. The eastern cape was once home to tremendous herds of elephant which were hunted by the Xhosa and the Khoe (Khoi) tribes for sustenance, and much like the American Plains Indians and buffalo it did not end well. As colonization spread across the region in the 1700 and 1800s the tribes succumbed to smallpox and were pushed into different regions, and the elephants were slaughtered to near extinction for their ivory and to protect farming interests in the region. With the killing of 1400 elephants in 1919, public opinion slowly turned. Only eleven elephants remained when Addo Park was established in 1931 with 5600 acres.

The eastern cape was once home to tremendous herds of elephant which were hunted by the Xhosa and the Khoe (Khoi) tribes for sustenance, and much like the American Plains Indians and buffalo it did not end well. As colonization spread across the region in the 1700 and 1800s the tribes succumbed to smallpox and were pushed into different regions, and the elephants were slaughtered to near extinction for their ivory and to protect farming interests in the region. With the killing of 1400 elephants in 1919, public opinion slowly turned. Only eleven elephants remained when Addo Park was established in 1931 with 5600 acres.  The park was enclosed with an elephant proof fence in 1954, to protect the surrounding citrus farms from their rampages, when the size of the herd had rebounded to 22 elephants. Today the park is the third largest in South Africa and encompasses 1,700,000 acres. Home to over 600 elephants now, the reserve has expanded its mission to protect a growing number of mammal species within its borders.

The park was enclosed with an elephant proof fence in 1954, to protect the surrounding citrus farms from their rampages, when the size of the herd had rebounded to 22 elephants. Today the park is the third largest in South Africa and encompasses 1,700,000 acres. Home to over 600 elephants now, the reserve has expanded its mission to protect a growing number of mammal species within its borders. We could have done a self-drive tour through Addo, but we thoroughly enjoyed Edward’s knowledge of wildlife and the region. It was a good decision. Sitting up high in an SUV provided better visibility into the bush, where in our small rental car we wouldn’t have been able to see much. And his timing was perfect in getting us to a waterhole just as a very large herd with calves was creating a trail of dust as it emerged from the surrounding dry bush.

We could have done a self-drive tour through Addo, but we thoroughly enjoyed Edward’s knowledge of wildlife and the region. It was a good decision. Sitting up high in an SUV provided better visibility into the bush, where in our small rental car we wouldn’t have been able to see much. And his timing was perfect in getting us to a waterhole just as a very large herd with calves was creating a trail of dust as it emerged from the surrounding dry bush. We witnessed elephants smiling as they drank. It was a tremendous experience.

We witnessed elephants smiling as they drank. It was a tremendous experience.

As if guarding the plaza,

As if guarding the plaza,

Shady Miradouro de São Pedro de Alcântara overlooks this colorful chaos and has splendid views of Lisbon below. From the miradouro it’s a gentle uphill walk into Bairro Alto. Fortunately, there’s no lack of places to rejuvenate yourself along the way. For lunch we found

Shady Miradouro de São Pedro de Alcântara overlooks this colorful chaos and has splendid views of Lisbon below. From the miradouro it’s a gentle uphill walk into Bairro Alto. Fortunately, there’s no lack of places to rejuvenate yourself along the way. For lunch we found

Set in a historic 1890s building in Cais do Sodré, this is a huge, lively food court with numerous restaurant choices that is very popular with Lisboans. Whatever you are craving at the time, you’ll find something satisfying here. Next door, during the week, Mercado da Ribeira operates a central market with fish, meat and produce vendors offering Portugal’s finest products. Brightly painted Pink Street, popular for its club scene, is nearby.

Set in a historic 1890s building in Cais do Sodré, this is a huge, lively food court with numerous restaurant choices that is very popular with Lisboans. Whatever you are craving at the time, you’ll find something satisfying here. Next door, during the week, Mercado da Ribeira operates a central market with fish, meat and produce vendors offering Portugal’s finest products. Brightly painted Pink Street, popular for its club scene, is nearby.

Heading west, tram 28 weaves through a very narrow section similar to parts of its route in Alfama, before reaching the open area around Assembleia da República. The parliament of Portugal is headquartered in a neoclassical building that was first used as a convent in the sixteenth century. Formal gardens behind the parliament building, hidden by an imposing wall, can be seen from tram 28 or if you stand on your tip-toes and peer over. Never immune from criticism, the politicians must endure a large satirical wall mural, painted on a nearby building, as they head to work each day.

Heading west, tram 28 weaves through a very narrow section similar to parts of its route in Alfama, before reaching the open area around Assembleia da República. The parliament of Portugal is headquartered in a neoclassical building that was first used as a convent in the sixteenth century. Formal gardens behind the parliament building, hidden by an imposing wall, can be seen from tram 28 or if you stand on your tip-toes and peer over. Never immune from criticism, the politicians must endure a large satirical wall mural, painted on a nearby building, as they head to work each day.

The scenery along the drive to Lake Atitlan, along roads that continued to climb higher, was spectacular with verdant greenery and distant volcanos appearing then disappearing again with each twist of the serpentine route.

The scenery along the drive to Lake Atitlan, along roads that continued to climb higher, was spectacular with verdant greenery and distant volcanos appearing then disappearing again with each twist of the serpentine route.  Arriving in San Pedro we thought we were on a movie set for a sequel to Mad Max or Water World. Down by the Panajachel dock dreadlocked travelers, wearing eccentric attire, filled the streets along the lakeshore. Feeling as if we had time traveled, we were relieved to find our Airbnb far out of town on a dead-end road that ran along the lake. According to Google maps the road was unnamed. Our host said “tell the tuktuk drivers you are staying on Calle Finca,” which referred to a distant and abandoned coffee farm, about an hour’s walk from the trail head at the end of the road.

Arriving in San Pedro we thought we were on a movie set for a sequel to Mad Max or Water World. Down by the Panajachel dock dreadlocked travelers, wearing eccentric attire, filled the streets along the lakeshore. Feeling as if we had time traveled, we were relieved to find our Airbnb far out of town on a dead-end road that ran along the lake. According to Google maps the road was unnamed. Our host said “tell the tuktuk drivers you are staying on Calle Finca,” which referred to a distant and abandoned coffee farm, about an hour’s walk from the trail head at the end of the road. Our new home for our last week in Guatemala had a wonderful porch with great view of Lake Atitlan and tranquility. A relaxing change of pace was called for after the Christmas and New Year’s Day celebrations in Antigua. Bird calls or the soft Mayan chatter of coffee pickers, harvesting ripe beans right outside our door, were the only sounds that filled the air. Fortunately, we were much closer to town than the abandoned coffee finca and were able to walk to the daily outdoor market, along streets where we could see women washing clothing in the distant lake, and make-shift scales were set up to buy coffee beans hauled down from the slopes of Volcan San Pedro.

Our new home for our last week in Guatemala had a wonderful porch with great view of Lake Atitlan and tranquility. A relaxing change of pace was called for after the Christmas and New Year’s Day celebrations in Antigua. Bird calls or the soft Mayan chatter of coffee pickers, harvesting ripe beans right outside our door, were the only sounds that filled the air. Fortunately, we were much closer to town than the abandoned coffee finca and were able to walk to the daily outdoor market, along streets where we could see women washing clothing in the distant lake, and make-shift scales were set up to buy coffee beans hauled down from the slopes of Volcan San Pedro.

A short ferry ride took us to San Juan La Laguna, a weavers and artists village that visually celebrates its Mayan heritage with colorful street murals. The steep walk uphill from the boat dock to the center of town was lined with art galleries.

A short ferry ride took us to San Juan La Laguna, a weavers and artists village that visually celebrates its Mayan heritage with colorful street murals. The steep walk uphill from the boat dock to the center of town was lined with art galleries.

Six years ago, when we first visited the lake, we stayed at Posada de Santiago in Santiago de Atitlan and met Carolina, an American expat who has been in Guatemala going on thirty years now. We’ve stayed in touch over the years. Being so close by, a reunion was in order.

Six years ago, when we first visited the lake, we stayed at Posada de Santiago in Santiago de Atitlan and met Carolina, an American expat who has been in Guatemala going on thirty years now. We’ve stayed in touch over the years. Being so close by, a reunion was in order. It’s a long ferry ride to Santiago de Atitlan and even longer when the wind churns up whitecaps on the water, and the small boat we were in rocked side-to-side for the duration of the crossing. We silently said our prayers when the local folks stated to reach for the life preservers. Fortunately, we were never too far from shore and know how to swim. It is a breathtaking view coming into the boat dock at Santiago with its namesake volcano towering over the town and Volcan San Pedro just an avocado toss away, across the water.

It’s a long ferry ride to Santiago de Atitlan and even longer when the wind churns up whitecaps on the water, and the small boat we were in rocked side-to-side for the duration of the crossing. We silently said our prayers when the local folks stated to reach for the life preservers. Fortunately, we were never too far from shore and know how to swim. It is a breathtaking view coming into the boat dock at Santiago with its namesake volcano towering over the town and Volcan San Pedro just an avocado toss away, across the water.

Enjoying the stars from our porch we were surprised when fireworks celebrating Epiphany lit up the night sky above villages across the lake, their colorful bursts reflected brilliantly on the water. With magical moments like this, still fresh in our memories, Guatemala tugged at our hearts as we packed for our next adventure.

Enjoying the stars from our porch we were surprised when fireworks celebrating Epiphany lit up the night sky above villages across the lake, their colorful bursts reflected brilliantly on the water. With magical moments like this, still fresh in our memories, Guatemala tugged at our hearts as we packed for our next adventure.

Paradise is such a subjective feeling and if you don’t require a turquoise blue sea and white sand beaches, Antigua, Guatemala just might fit the bill. This charming colonial city with its ever spring-like weather was perfect for our two-month stay.

Paradise is such a subjective feeling and if you don’t require a turquoise blue sea and white sand beaches, Antigua, Guatemala just might fit the bill. This charming colonial city with its ever spring-like weather was perfect for our two-month stay.  We arrived in Antigua at the end of October so that we could attend the Sumpango Giant Kite Festival held every year on November 1st, All Saints Day. That spectacularly colorful event and a religious procession that burst forward from La Merced Church on October 28th would prove to be representative of the people and life in Guatemala we experienced.

We arrived in Antigua at the end of October so that we could attend the Sumpango Giant Kite Festival held every year on November 1st, All Saints Day. That spectacularly colorful event and a religious procession that burst forward from La Merced Church on October 28th would prove to be representative of the people and life in Guatemala we experienced.

On Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays the market tripled in size when the outdoor portion was open, and farmers brought in truckloads of fruits and vegetables from the surrounding villages. There we experienced one of the best markets going, set in a bustling, dusty lot with Volcans Agua, Fuego and Acatenango touching the sky in the background. Most produce was sold in quantities of 5 quetzals (60 cents) so bring lots of small bills, as vendors didn’t usually have change for anything larger than 10Q. The flavor of the locally grown vegetables was amazing. Being backyard gardeners ourselves, we were duly impressed. Twenty quetzals would buy enough vegetables for a week.

On Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays the market tripled in size when the outdoor portion was open, and farmers brought in truckloads of fruits and vegetables from the surrounding villages. There we experienced one of the best markets going, set in a bustling, dusty lot with Volcans Agua, Fuego and Acatenango touching the sky in the background. Most produce was sold in quantities of 5 quetzals (60 cents) so bring lots of small bills, as vendors didn’t usually have change for anything larger than 10Q. The flavor of the locally grown vegetables was amazing. Being backyard gardeners ourselves, we were duly impressed. Twenty quetzals would buy enough vegetables for a week.

Shopping at the local supermarket, La Bodegona, was a wonderfully hectic experience. At times it could feel like you were shopping from a conga line, weaving up and down aisles, afraid to leave the line for fear of not being able to enter it again and being stuck in dairy for eternity. Numerous store employees lined the aisles offering samples of cookies, deli meats, drinks and other temptations to keep the energy level of the beast alive. It was a hoot! We had to psych ourselves up, like players before the big game, to shop there because it was so hectic and required a certain mental and physical stamina. I will confess though to dancing in the checkout line to blaring Latino Christmas music – the mood was contagious.

Shopping at the local supermarket, La Bodegona, was a wonderfully hectic experience. At times it could feel like you were shopping from a conga line, weaving up and down aisles, afraid to leave the line for fear of not being able to enter it again and being stuck in dairy for eternity. Numerous store employees lined the aisles offering samples of cookies, deli meats, drinks and other temptations to keep the energy level of the beast alive. It was a hoot! We had to psych ourselves up, like players before the big game, to shop there because it was so hectic and required a certain mental and physical stamina. I will confess though to dancing in the checkout line to blaring Latino Christmas music – the mood was contagious.  On the same block D&C Cremas, a Walmart affiliate, offered a more sedate shopping experience. Both supermarkets had excellent poultry, which was more tender and tastier than back in Pennsylvania. We were also fortunate that a pork butcher opened a new shop a half block away and offered fresh meat and sausage daily. We enjoyed all the different varieties of Guatemalan sausage he made and found them to be very flavorful and lean, with almost no fat.

On the same block D&C Cremas, a Walmart affiliate, offered a more sedate shopping experience. Both supermarkets had excellent poultry, which was more tender and tastier than back in Pennsylvania. We were also fortunate that a pork butcher opened a new shop a half block away and offered fresh meat and sausage daily. We enjoyed all the different varieties of Guatemalan sausage he made and found them to be very flavorful and lean, with almost no fat.

The next day we a followed a serpentine mountain road, second gear all the way, up to Santo Domingo del Cerro, a beautiful sculpture and art park with museums, walking trails and a restaurant that overlooks Antigua. Plan on spending at least a half day there, because it is a beautiful setting for a restful day or afternoon. Casa Santo Domingo offers a free hourly shuttle to the park from the hotel in town.

The next day we a followed a serpentine mountain road, second gear all the way, up to Santo Domingo del Cerro, a beautiful sculpture and art park with museums, walking trails and a restaurant that overlooks Antigua. Plan on spending at least a half day there, because it is a beautiful setting for a restful day or afternoon. Casa Santo Domingo offers a free hourly shuttle to the park from the hotel in town.

Antigua filled early with people in all their finery on New Year’s. Vendors selling textiles the day before were now offering party hats and all sort of 2019 memorabilia. Concerts were held in Plaza Mayor and under El Arco. Firework launchers were being setup amidst the crowds in the streets. Families were picnicking in the park and folks were staking their spots early to watch the fireworks later. At midnight a loud and colorful display filled the night sky. We could hear the roar of an appreciative crowd from our rooftop. We heard random explosions throughout the night to sunrise. Guatemalans love their fireworks!

Antigua filled early with people in all their finery on New Year’s. Vendors selling textiles the day before were now offering party hats and all sort of 2019 memorabilia. Concerts were held in Plaza Mayor and under El Arco. Firework launchers were being setup amidst the crowds in the streets. Families were picnicking in the park and folks were staking their spots early to watch the fireworks later. At midnight a loud and colorful display filled the night sky. We could hear the roar of an appreciative crowd from our rooftop. We heard random explosions throughout the night to sunrise. Guatemalans love their fireworks!

The city does a wonderful job supporting its craftspeople who still use traditional, made by hand, methods to create exceptional pieces in jewelry, textile, ceramic, wrought-iron, tin and copper workshops located across the city. Toquilla straw weavers in the villages around Cuenca who carry unfinished sacks of Panama Hats into the city’s sombrero (hat) factories also need to be included into this group. There are also several traditional felt hat tallerias (workshops) that cater to the indigenous women who live in the rural areas around Cuenca. The fine arts scene is also well represented with galleries and artists’ studios often next to traditional crafts workshops. To get the broadest experience of this vibrant arts and crafts community a tour through Cuenca’s most interesting neighborhood, El Barranco (the cliffs), and along its busiest street Calle Larga, is a must. The colonial buildings that front Calle Larga back onto the cliff which overlooks Rio Tomebamba and the newer southern part of Cuenca. Wide stairs in several parts lead down to Paseo 3 de Noviembre, a shaded pedestrian walkway and bike path that follows the river for several miles.

The city does a wonderful job supporting its craftspeople who still use traditional, made by hand, methods to create exceptional pieces in jewelry, textile, ceramic, wrought-iron, tin and copper workshops located across the city. Toquilla straw weavers in the villages around Cuenca who carry unfinished sacks of Panama Hats into the city’s sombrero (hat) factories also need to be included into this group. There are also several traditional felt hat tallerias (workshops) that cater to the indigenous women who live in the rural areas around Cuenca. The fine arts scene is also well represented with galleries and artists’ studios often next to traditional crafts workshops. To get the broadest experience of this vibrant arts and crafts community a tour through Cuenca’s most interesting neighborhood, El Barranco (the cliffs), and along its busiest street Calle Larga, is a must. The colonial buildings that front Calle Larga back onto the cliff which overlooks Rio Tomebamba and the newer southern part of Cuenca. Wide stairs in several parts lead down to Paseo 3 de Noviembre, a shaded pedestrian walkway and bike path that follows the river for several miles. This route actually starts several blocks west of Calle Larga at Cuenca’s Museo de Arte Moderno (Museum of Modern Art) across from Parque de San Sebastian which has a large fountain and several nice places to eat. Casa Azul, which has rare sidewalk tables that face the quiet plaza, and Tienda Café are good choices. Most of the workshops won’t have business signs over their doors or street numbers, might open by ten, but will reliably close between one and three for lunch.

This route actually starts several blocks west of Calle Larga at Cuenca’s Museo de Arte Moderno (Museum of Modern Art) across from Parque de San Sebastian which has a large fountain and several nice places to eat. Casa Azul, which has rare sidewalk tables that face the quiet plaza, and Tienda Café are good choices. Most of the workshops won’t have business signs over their doors or street numbers, might open by ten, but will reliably close between one and three for lunch.