“Could you recommend any restaurants for lunch?” The young car rental agent seemed surprised, at first, that we asking her opinion. “Where are you staying. What do you like?” “In the center of Funchal. Meat, fish, we enjoy everything,” I replied. “Hah, most places in Funchal will be closed for the mid-afternoon break by the time you reach town, but nearby, though it’s in the opposite direction, there is Restaurante Snack-bar Frente Ao, one of my favorite places.” And so, our Madeira adventure began with a delicious lunch in a no-frills local place. Tasty grilled limpets in a buttery garlic sauce started our meal. A traditional Polvo a Lagareio, baked octopus with potatoes, and scabbardfish served with fried bananas followed. It was scrumptious, heavenly, you get my point, it was really GOOD! Outside, planes flew close to the water on their final approach to FNC, across a panorama of the coast that stretched all the way to the headland of Ponta de São Lourenço.

Our first short drive to the restaurant revealed a verdant, lush tropical island bursting with flowering plants, and mountainous with steep ravines that descended into the ocean, like the radial arms of a spider’s web, from a central ridge that runs the length of the island. Colorfully painted homes with red tiled roofs dotted the countryside like swathes of pigment in an impressionist painting. There are few direct, only circuitous routes, where even the bridges and tunnels, some almost 2 miles long, curve to follow the contour of the land. Banana groves large and small dotted every plot of land between the homes that covered the hillsides. Three vintage cars zoomed by.

Portuguese sailors blown 300 miles off course by a violent storm as they explored the west coast of Africa in 1418 discovered a small uninhabited island, with a sheltered anchorage, where they rode out the storm. In thanks they christened the island Porto Santo, Holy Harbor. They noted in a ship’s log that on the western horizon a “dark monstrous shape loomed.” A year later they returned. Wood, madeira, from its virgin forests was the island’s first exports. The trees were so tall and straight that they allowed the Portuguese to design larger, sturdier ships, which Vasco da Gama’s fleet used to sail to India in 1497.

Felling trees for export opened the hillsides for extensive terracing of the lower slopes in the mid-1500s, when sugar cane became the prized export. Later grapes were introduced, and Madeira wine was born. Both crops thrived with irrigation provided by an extensive series of arduously cut, narrow channels called levadas, which traverse the rugged terrain and divert water from mountain streams to the agricultural terraces across the island. Their water was also used to turn the waterwheels of the first mills on the island. Close to five-hundred miles of levadas cover this mountainous island that is roughly thirty-four miles long and fourteen miles wide.

With Madeira wine came the English, who believed that fortified wines improved with age on long ocean voyages. Sailing to their various colonies in the Americas, English naval and merchant ships would sail south from England to catch the trade winds blowing west off Morocco. Fortuitously, Madeira was a well-placed port of call to resupply. With full sails and barrels of Madeira wine in the ship’s hold, they’d reach the Caribbean in a month’s time. Farther on, in their New England colonies, members of the Continental Congress toasted the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776 with Madeira wine. While being notoriously at odds with Spain for centuries, the Brits and the Portuguese have the world’s oldest alliance which stems from the Treaty of Windsor in 1386 and was fortified, port glasses raised, with the marriage of King John I of Portugal to a daughter of John of Gaunt, Philippa of Lancaster. This treaty of mutual support has lasted over 630 years. Cheers!

Captain Cook and Charles Darwin both visited at the beginning of their explorations. Napoleon in 1815 stopped for a final supply of Madeira wine while enroute to his permanent exile on St Helena. With the advent of steamships, Madeira became a destination for the well to do of Europe. Before the quay was constructed, historical photos show merchants rowing long boats laden with supplies out to ships anchored in the harbor, and returning with visitors to disembark on Funchal’s rocky beach. Doctors recommended its good fresh air for patients convalescing from tuberculosis. Winston Churchill visited in 1950, painted seascapes and stayed at Reid’s Palace, a Madeira institution since 1891 that still serves afternoon high tea. He left the island with a reputation that it was for stogey old folks, that remained for decades.

But with Portugal joining the European Union in 1986, it enabled a massive investment in infrastructure that united all parts of the island that were previously inaccessible by overland routes. The small island now has over 100 tunnels and bridges, along with seven cable car routes scattered around the island. Across from the cruise terminal at the base of Santa Catarina Park, there is a relief statue set into a granite embankment that commemorates the men who toiled to build the island’s tunnels and terraces.

Flat land is a rarity on Madeira, as is landfill, the lack of which required the airport runway extension in 2000 to be uniquely expanded over the ocean on 180 concrete columns, each of which are 230-foot-tall, for a total length of 9,000 feet. It felt like we were going to land on an aircraft carrier. Fifty-eight cities in twenty-one countries now have direct flights to the island. Cruises to the island continue to be popular and in 2022 Madeira was voted by the World Cruise Awards the Best Cruise Destination in Europe. Madeira has now reinvented itself into a destination packed with outdoor activities that include sailing, whale watching, surfing, paragliding, scuba diving, and mountain hikes for all levels of fitness.

Our hotel, São Francisco Accommodation, was a modest three-star hotel centrally located in Funchal’s historic old town. The big pluses for us were its elevator, underground parking lot across the street, and its location. The most interesting parts of Madeira’s capital city were within walking distance of our lodging. We were set for the week! We chose to stay in Funchal because it is the island’s largest city, with enough things to do locally so we wouldn’t feel the need to go elsewhere. The car was for day trips to explore the rest of the island.

One afternoon we were drawn down the street by the sound of classical music flowing from the park around the corner from the hotel. Folks casually filled a small amphitheater in the midst of a manicured garden. Next to the bandstand a small kiosk offered a table. We ordered drinks and enjoyed the afternoon entertainment. At the bottom of the park people mingled around a line of classic cars parked along the street.

Delightfully, Madeirans out of necessity have inadvertently created a sub-culture of serious vintage car enthusiasts. Importing cars to the island has always been very expensive. Consequently, automobiles have become family heirlooms. Many of them are passionately maintained or restored and passed down through the generations. So common is the practice that over 800 vintage cars are registered on this small island. Their enthusiasm is celebrated each year with the Madeira Classic Car Revival, a three day event that culminates with a race along the Praça do Povo waterfront every May.

Several mornings we were up before dawn to walk along the waterfront in search of the ultimate sunrise shots with the unpopulated islands Selvagens and Desertas silhouetted on the horizon. We were not disappointed.

There were numerous interesting photo opportunities from the marina to Forte de São Tiago, which was built in the early 1600s in response to two brutal attacks by pirates. French pirate Bertrand de Montluc assaulted the town in 1566 with three ships. Mayhem ensued as his cut-throats rampaged and plundered the streets for fifteen days. Then Barbary pirates with eight ships ransacked Funchal in 1617 and took 1200 people back to Algiers as slaves. Now, under the ramparts of the fort, pensioners enjoyed ritualistic morning swims along a peaceful, pebbly Praia de São Tiago.

Around the corner from the fortress at the Miradouro do Socorro, a pretty arbor frames the view of the sea and the Complexo Balnear da Barreirinha, a waterfront day resort where you can rent a lounger and swim in their pool or the sea. Across the street the Igreja de Santa Maria Maior, a small parish church, serenely graces the neighborhood.

Heading back into town we walked along the Rua de Santa Maria, a narrow alley known for the uniquely painted doors on homes, galleries and restaurants that line the street. To see many of the doors you have to visit the street early before the shops open them for the business day.

In front of the Mercado dos Lavradores, the town’s old central market, there is a bronze statue depicting a merchant driving a team of oxen pulling a flat wooden pallet loaded with barrels of wine. Versions of these toboggans fitted with wicker chairs were called Carro de Cesto. Until roads were introduced in 1904 to accommodate the first cars brought to the island, this was the preferred downhill method of public transport, as a wheeled cart might run away uncontrollably if there was a mishap.

Today, at the steps before the Nossa Senhora do Monte Church, toboggans filled with tourists are pushed downhill by two men, Carreiros, donning wicker hats and traditional white outfits. Hold on, the steep serpentine course is over a mile long and the sleds can go almost 25 miles an hour! There are no brakes, only the special, rubber-soled shoes the carreiros wear, and stopping is accomplished by dragging their feet along the road to slow the toboggan. It’s a popular activity easily combined with a cable car ride from the Funchal waterfront to the Monte Palace Tropical Garden.

Though when we visited we chose to use our car instead of taking the cable car to Monte. We didn’t realize when we started but the google map route we followed to the garden was up one of Funchal’s steepest streets. The Caminho de Ferro takes its name from the old funicular train tracks upon which the road was paved. It runs for two miles straight up a hill with a twenty-five-degree slope and gains nearly 2000ft in altitude. I was doing fine driving uphill in second gear until we encountered a semi-blind cross street that did not have a stop sign, only a large traffic mirror. This was something I hadn’t encountered before, so I came to a complete stop. The incline of the road was very steep at this point, and I had difficulty getting the car moving again without rolling back too far. Ultimately after several frustrating minutes I rolled the car back perpendicularly to the road, got the car in gear and powered slowly through the intersection. Fortunately, there is very little car traffic on the side roads in Funchal and we lucked out in finding a parking space near the garden. The return route into the city center, down streets so narrow it required pulling the mirrors in, was equally challenging.

In the 1700s the hillside that the garden covers was a private estate with a small chateau. Later it functioned as a grand luxury hotel. In 1987 the entrepreneur Jose Manuel Rodrigues Berardo acquired it and transformed it into a serene Japanese themed botanical garden and opened it to the public. It’s a beautiful tranquil landscape, but it’s best to arrive early or late to avoid a crowd. There is also collection of contemporary Zimbabwean stone sculptures from the 1960s and a cave created to display a spectacular mineral collection gathered from around the world.

Slightly smaller and lower on the slope the Jardim Botânico da Madeira is also worth a visit to experience its stunning formal garden with a view of the Funchal coastline, and paths that weave through various plantings. There is also a nice cafe with a terrace that has one of the best views of Funchal.

However, if you enjoy orchids the place to head is the Quinta da Boa Vista. It’s a quirky plant nursery that has been operated by several generations of the Garton family and has hundreds of different orchids. As we entered the first greenhouse, an eager attendant waved us over and encouraged us to smell a delicate plant she was holding. An Oncidium Sharry Baby, it had a delicate chocolate aroma. It was delightful. With two stunning botanical gardens in Funchal and smaller ones seeded around the island, Madeira justly earns its nickname as “The Floating Garden of the Atlantic.”

Earlier we had spotted the hulking edifice of the Fortaleza de São João Baptista do Pico. A 17th century stronghold, it was built high on a hill, 350 feet above Funchal’s waterfront to deter pirate attacks. It’s a wonderful destination within town, with a nice children’s playground and café outside the fortress battlements. The view out over the city and ocean was spectacular.

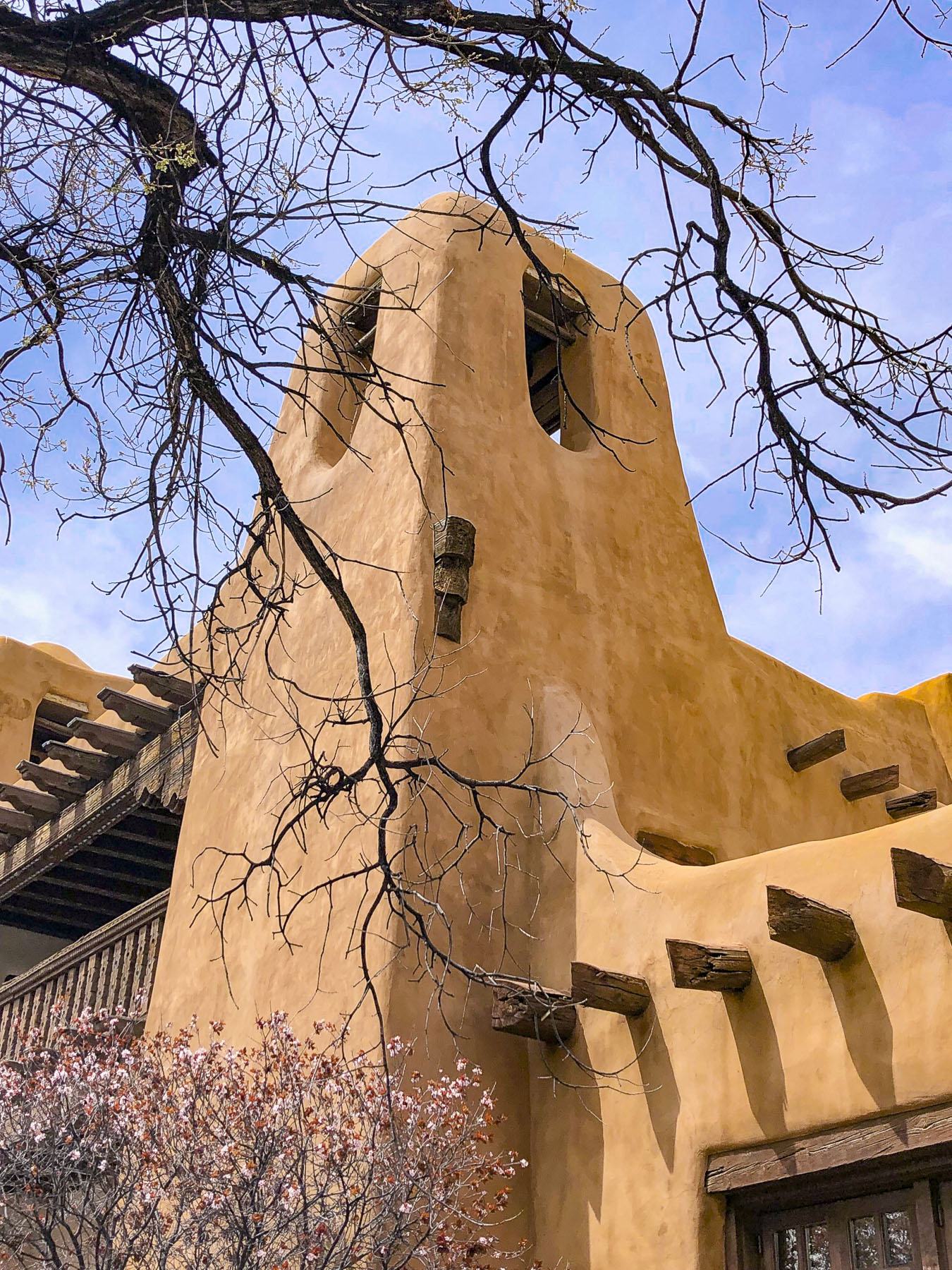

Other mornings we explored closer to home heading to the Igreja de São João Evangelista, on Funchal’s central plaza. Built by Jesuits in 1629, it is known for the fusion of its Mannerist exterior with a lavish Baroque interior.

We climbed to the church’s roof for an exceptional view of the old town. Funchal’s City Hall is adjacent to the church and has a stately courtyard centered around a unique fountain depicting Leda and the Swan. An odd choice we thought for decorating a municipal building.

But Funchal is very supportive of public art and we passed many interesting sculptures along our walks. The historic old town with its cobbled lanes lined with centuries old buildings and churches was a delight to explore.

One morning we photographed small boats leaving the port at sunrise from Parque de Santa Catarina, which commands a bluff across from the cruise terminal.

From the park we walked along Rua Carvalho Araujo up into São Martinho, an upscale area anchored by Reid’s Palace. Occasionally we popped into the hotels that faced the water to check out their views.

But there is more to this island than just Funchal, so we hopped in the car for farther explorations west along the coast. Our first day trip was on a Saturday afternoon to Câmara de Lobos, famous as a favorite spot for Winston Churchill to paint. A newly married couple was taking wedding photos amid the colorful small boats pulled ashore as young children splashed and played with their dog in the shallow surf that splashed against the boat ramp.

Parallel parking on a steep incline was challenging, but it’s a skill that’s required on Madeira, and came in handy when we reached the Cabo Girão Skywalk, one of the highest cliffs in Europe. Relatively close to Funchal, this is a popular destination and there was actually a traffic jam as cars and buses creatively parked. This glass bottomed miradouro seems to hover miraculously over fertile fields that grow grapes and tomatoes nineteen-hundred feet below. Nearby the Cabo Girão cable car, originally built to help farmers bring their crops up from the fields, can whisk you down to a secluded beach. We have a healthy fear of heights and instead continued on.

I wasn’t fast enough with my camera to grab a photo of a paraglider swooping low over our car as he landed along the stoney beach at Cais da Fajã do Mar. High above us a group of paragliders swirled on warm thermals and we waited for them to descend, but they kept floating back over the ridge.

We meandered farther west to the beach and harbor, dramatically wedged between ocean and mountain, in Estreito da Calheta. This is a largely human-altered section of the coast with a breakwater protecting Praia da Calheta, created with imported sand, and harbor next to it. We ate lunch on the promenade across from the marina.

Heading back to Funchal later that afternoon we made a final stop in Ponta do Sol, and were able to find sanctioned parking in one of Madeira’s older, now decommissioned traffic tunnels. Walking out to a small headland we had late afternoon refreshments on a terrace with a brilliant view of the coastal village.

“Roll up your window.” “Wait, you’re not going to…” Yee haw! I yelled and we laughed while a thunderous cascade of water splashed off the roof of our car as we drove under the Cascade of Angels waterfall.

Till next time, Craig & Donna

Please share my page with your friends