“The old timers say on a stormy day like this you can hear their cries on the wind when you pass through Borove,” our host commented mysteriously as he learned of our plans to drive along the SH75 towards Voskopoja and then Korce. Evidence of Albania’s new investments in its road infrastructure to support tourism in southeastern part of the country were visibly apparent, with bridges being repaired, as well as sections of the road being widened, and repaved along our serpentine route through beautiful, forested mountains. The mountains finally receded behind us as we coasted downhill into a wide valley with gently rolling hills.

As we rounded a bend, a tall brooding silhouette loomed over the road. The statue of two resistance fighters captured in a decisive moment of attack commemorates the July, 1943 partisan ambush of a German troop convoy through the valley, near the hamlet of Barmash. The battle raged for hours and left 60 enemy soldiers dead, and numerous vehicles destroyed. Sadly, the second part of this event revealed itself several miles away in the larger village of Borove. Here stairs on the outskirts of the village quietly led to the top of a knoll and the Memorial i Viktimave të Masakrës së Borovës. This heart-rending site contains the graves of 107 men, women and children massacred the next day when Nazi troops returned to the area and set their village ablaze in retaliation. It’s a moving memorial, and we stayed until a pounding rain forced us back to our car.

Farther along we passed through Ersekë. It’s one of Albania’s highest towns, sitting at an elevation of 3,445 ft on a high plain, in the shadow of the Greece’s Pindus mountain range. This southeastern part of Albania is very remote, and the village so close to the Greek border, that during the communist era villagers were prevented from leaving the town, on the fear that an abandoned village on the border would invite Greek expansionism. The town is most noticeable for its well-maintained communist era minimalistic architecture.

Reaching Korce we turned west onto SH63 and headed back into the mountains, our destination, the ancient Orthodox churches of Voskopoja. Light rain turned into 3 inches of wet snow as we drove higher into the mountains. This didn’t particularly faze us as we both have decades of experience driving on wintry roads in northeastern United States. But the drastic change of weather did, considering 10 days earlier, when we arrived in Tirana we rejoiced in 80F weather for several days earlier in the month. The saving grace – there were literally no other cars on the road.

On a snowy Sunday afternoon in late April we practically had the whole town to ourselves. It was quite serene and beautiful with the fresh snow clinging to the trees, and tufts of spring greenery poking through the snow on the ground. We found Saint Nicholas Church and gingerly made our way down the puddled walkway to shelter under the exonarthex and shake the snow off our jackets before entering the sanctuary.

The walls of this covered porch area were painted with illustrative religious stories designed to visually educate the illiterate, warn the sinners, and inspire the devout, before entering the church. Sadly, the frescoes show the scars from being vandalized during the Ottoman era, but their beauty is still evident.

We had expected a caretaker to be present, though no one was around, but the door to the church was unlocked and we entered. The ancient cavernous space was barley lit with only two bare bulbs and the light from several small windows, but it was enough to see that every surface of the whole interior was beautifully illuminated in ancient orthodox iconography.

Liturgical music was faintly audible in the background as we admired the artisitic vision and faith that inspired this moving creation. Constructed in 1721, the frescoes are attributed to the painter David Selenica, and his assistants, the religious brothers Constantine and Christos.

This team also famously painted religious iconography in the monasteries on Mount Athos. It’s amazing the church survived several centuries of turbulent history, only to be atrociously used as a storage depot during the communist era. The church, as beautiful as it is, was also a little spooky with centuries of candle soot covering the walls and gilded wood-carved iconostasis. Afterwards we headed to Kisha e Shën Mëhillit, the Church of Saint Michael, 1722, just on outskirts of the village and found it surrounded with scaffolding. Though disappointed, this was an encouraging sign that restoration was under way. Unfortunately, the road leading to the Church of St. Elija, the last church built in Voskopoja in 1751, was under repair and a muddy mess that deterred us from reaching it. But we did get to view the Shënepremte Church perched on a hill above an old Ottoman era bridge. By mid-afternoon our stomachs were growling and we feared there wouldn’t be a place open to eat in the village. (This is an issue during off-season travel when many establishments close. It’s wise to bring snacks along.) Luckily, we found the Taverna Voskopojë open, and full of activity that Sunday afternoon. Their lakror, a pastry-style traditional Albanian pie, filled with ground meat or vegetables, is common to the Korçë region, and was delicious. The house wine was also very good.

First mentioned in 14th century historical records, Voskopoja was once one of the largest cities outside Istanbul, and the most important trading, cultural and religious center in the Balkans from the 1600’s to the 1800’s. It was during this height of prosperity that the city had an estimated population of between 30,000 – 60,000 and supported 26 Orthodox churches richly decorated with Byzantine frescoes; the only printing house in the Balkans; and a New Academy or Greek school. Its influence and wealth stemmed from metal smithing, wool processing and tanneries. Merchandise from these industries supplied the traders that traveled along the Tsarigrad Road. The road was an old caravan route that connected Rome to its colonies in Sofia and Plovdiv, Bulgaria, before reaching Tsarigrad, the Slavic name for Constantinople. In later centuries the route passing through Voskopoja connected it to the Venetian ports on the Adriatic Sea and Belgrade.

The armies of Rome, the Huns, and the Ottoman Empire also followed this route through Albania and in the process brought new ideas and religions with them. During the Middle Ages the Christian Byzantine Empire encouraged the spread of the Eastern Orthodox religion into the Balkans along the ancient trade route, which was most famously followed by the early evangelists Cyril and Methodius. They made tremendous inroads with the pagan Balkan tribes by leading Mass, not in Latin, but in the Slavic language, an act many church leaders in Rome considered blasphemous at the time.

Voskopoja flourished peacefully under the Ottoman Empire’s millet system, where “Christians and Jews were considered dhimmi, protected, under Ottoman law in exchange for sworn loyalty to the state and payment of the jizya, a religious tax on non-Muslims,” until the 1768. Then the Russian-Ottoman war fueled an anti-orthodox sentiment and the government in Istanbul allowed Voskopoja in 1769 to be sacked and burned by Muslim tribes from the Dangëllia region around Përmet. The city was rebuilt, but twenty years later it was attacked, and razed to the ground again by the notorious Albanian warlord, Ali Pashë of Tepelena in 1789. After this the town never recovered its former glory and folks moved away to Korce and Berat, or farther afield into Bulgaria and Romania. It received additional damage during World Wars I & II. The final blow came in 1960 when a massive earthquake leveled many of the centuries-old churches, leaving only 5 standing in various states of disrepair. Today, the surviving churches are listed on the World Monuments Fund’s Watch List of 100 Most Endangered Sites. Only 600 year-round residents live in Voskopoja now, but this hidden gem is slowly being rediscovered and recognized as an interesting tourist destination for its many cultural and outdoor activities.

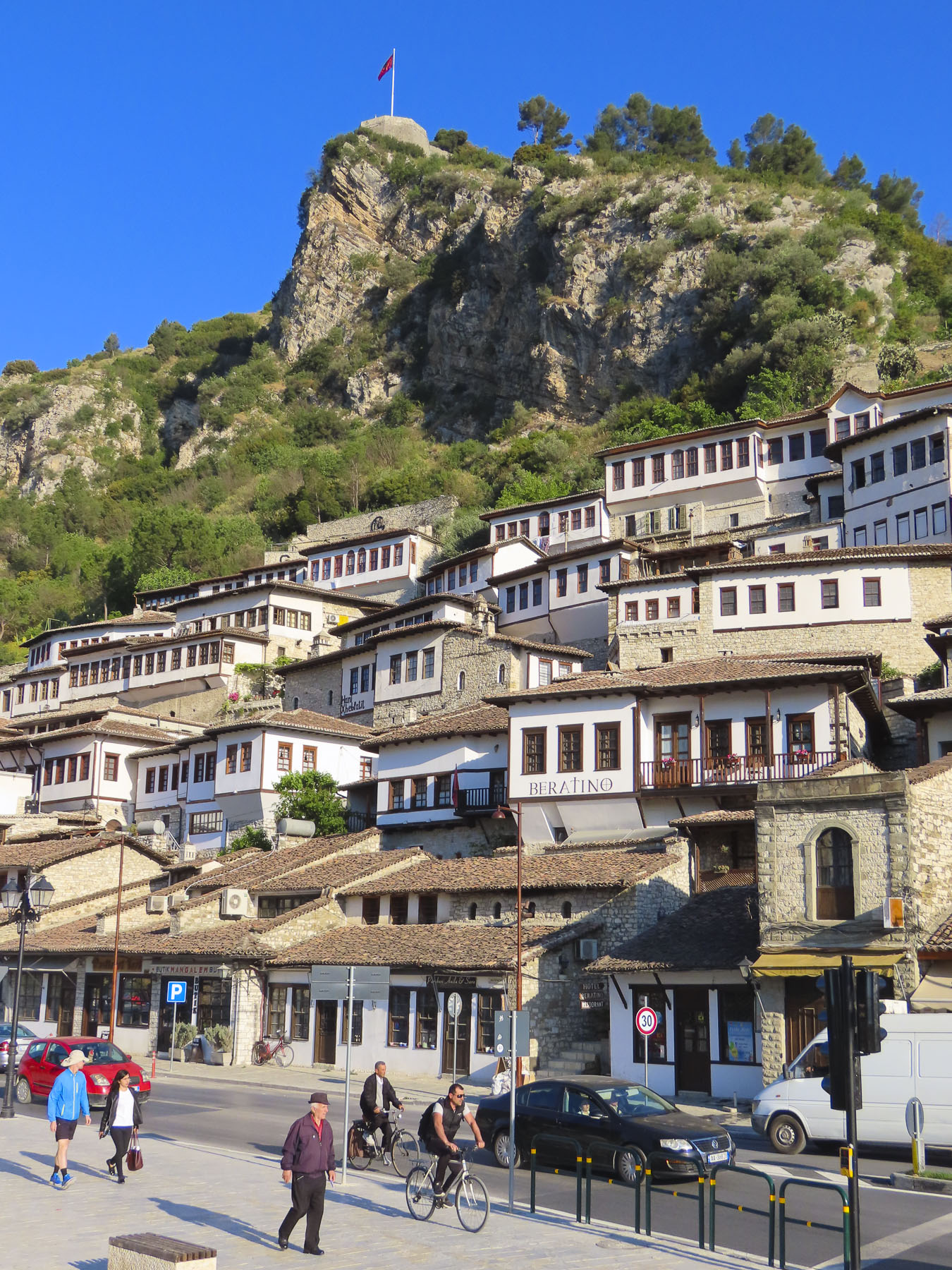

We drove back towards Korce under clearing storm clouds which dramatically revealed freshly snowcapped mountains dappled in sunlight. Situated in a wide fertile valley surrounded by the Morava mountains, Korce and the lands surrounding it were once the property of a feudal family in medieval times. Like Voskopoja, it benefited from trading with the caravans that trekked across routes to Thessaloniki in Greece, Istanbul and Southern Russia.

Traces of this industrious past can still be found along the cobbled lanes in the town’s colorful, old bazaar section, where deep-rooted merchants and craftsmen now share the lanes with cafes and chic shops.

A short walk away is Albania’s second oldest mosque, the Iljaz Mirahori. It’s named after the founder of Korce, and dates from 1496. Its original minaret was taken down during the communist era and not rebuilt until 2014.

The wide pedestrian mall, Bulevardi Shen Gjergji, which runs through the center of the city, along with the town’s many parks, helped Korce earn the moniker as “the Paris of Albania,” after the city was occupied by French troops during World War I.

With French support the local region existed briefly as the Republic of Korçë, from 1916-1920. In 1887, Mësonjëtorja, or the Albanian School, opened its doors to students on Bulevardi Shen Gjergji and taught students the Albanian language. This was a milestone in the Albanian National Awakening movement of the late 1800’s because until then giving lessons in the Albanian language was done in secret since Turkish was the official language under Ottoman rule.

Across from the pedestrian mall the Katedralja Ortodokse “Ringjallja e Krishtit,” aka, the Orthodox Cathedral “Resurrection of Christ,” grandly commands a plaza. Constructed in 1995, in Byzantine Revival-style, it is the largest orthodox church in Albania and replaces the St. John Church, which Albania’s former communist regime destroyed in 1968. It has a splendid interior covered with vibrantly new, orthodox religious imagery.

Anchoring the far end of the plaza, like a lighthouse on the ocean, is a modern seven-story skyscraper, the Sky View Hotel. It is the tallest building in Korce, and its architecture is very incongruous with the rest of the city, but that difference makes it very refreshing, and symbolizes Korce’s progressive future. It also had the best vantage points from its top floor restaurant, and our room, for taking pictures of the church and the surrounding snowcapped mountains. During our stay there we were surprised to learn that we were the hotel’s only guests on a Sunday and Monday in late April. Our room was very comfortable, and we enjoyed our stay. Additionally, it was very budget friendly, free parking was available on the street, and the staff was very nice.

The next morning, we drove into the foothills above Korce to the small village of Mborja. It took only 8 minutes to get there, but when we entered the Church of St. Mary it seemed like every minute of travel time transported us back a century. There is not a definitive record of when the Church of St. Mary was built, but it’s believed the small church was first constructed in 896 to honor Pope Clement I, and is the oldest Orthodox church in Albania. Later renovations were added in the 14th century.

We had entered the small, fenced yard that surrounds the church only to find its door locked tight. Luckily, two local women were walking by and acknowledged our dilemma with that global twist of the wrist, as if opening a door with a key. They motioned for us to wait and then headed downhill to the small produce shop we had just driven by. A few minutes later the guardian appeared. An elderly gentleman, he silently unlocked the door for us and invited us in. It was a small space, made even smaller by a solid stone wall with a half door in it which led to the altar.

It was difficult to bend so low, but I crouched down and entered. Donna followed. Whack! Ouch! “What happened?” “I cracked my skull on the door jamb!” Sympathetic to her injury, I tried to comfort her and divert her attention. “Babes, that was the kiss of God.” “Really!” “Yes, it’s in recognition for those twenty-four years of devoted service as a Methodist minister.” “Go away.” “Remember the Lord does work in mysterious ways.” A gentle elbow to my gut silenced me. Low doors were a common design feature of ancient churches built in areas prone to conflict.

The feature was used to prevent an invader from entering the sanctuary on horseback and defiling it. The compact interior was dark, but there was just enough light to see iconography on all the walls and the dome. The frescoes in the church are believed to be from the late 1300’s, and are in remarkably good condition, but the painter is unknown. The church is also an Orthodox pilgrimage site on Christ’s Ascension Day.

It was still well before noon when we reached to Kryqi Moravë, the Morovian Cross, which dramatically commands a mountain ridge above Korce. We had spotted it from miles away the other day as a ray of light caught it just right through clearing clouds. The parking area for it was only a 15 minute drive from Mborja. But the steep climb to the large cross and small chapel of Saint Elias on the ridge top took another 20 minutes.

The panoramic views over Korce, its valley, and the freshly snowcapped mountains were fantastic. You could literally see for miles all around. Back at the parking area we warmed ourselves with delicious cappuccinos at the Restaurant La Montagna. It’s a popular spot for folks to eat after spending a day hiking in the mountains.

On the way back downhill, we stopped at the Martyrs’ Cemetery on the hillside above Korce. It’s a beautiful location high above the city. The slope is lined with the simple graves of Albanian partisans who fought around Korce in WWII for the liberation of the country from German occupation. All the graves face west toward the setting sun. Many of the gravestones only contain a first or last name, and the year of death, the fighter’s year of birth unknown.

At the foot of the cemetery a monumental communist-era statue of a resistance fighter, with arm raised and fist clenched, stands victoriously over the city. It’s a powerful reminder of the ultimate price the partisans paid for what they thought would be a better future. These propagandistic communist statues can be found all around Albania and portrayed the communists as liberators, not the oppressors they truly were, who sent any political opposition to forced labor camps on trumped up charges of treason, and shot citizens who tried to escape the hardships of the regime for a better life elsewhere. It’s possible to walk from the city to the cemetery up a long stairway that starts at the top of Rruga Sotir Mero. Though the better way is to take a taxi up and walk down the stairway.

On the way back into the city for lunch in the old bazaar, we passed the Birra Korca. It’s Albania’s oldest brewery, capping its first bottles in 1928, and miraculously survived the communist decades as a state-owned business, though they ignored the old adage, “We know God loves us because he gave us beer.” The brewery and the city also host an annual Korca Beer Festival every August. It’s a week-long, city-wide event that draws thousands of folks to Korce.

In the old bazaar we sat outside at Taverna *Pazari i Vjeter* in a warm afternoon sun, and ordered, of course, two Korca beers, and some traditional dishes. Afterwards the waiter brought us Shahine plums. They are small sour green plums served as a digestive, and they were very tasty, much like a green apple. It was the first and only time they were offered to us in Albania, but if you have a chance to try them, go for it.

Till next time, Craig & Donna