With the assistance of our host, we rented a car and planned a four-day road trip heading up into the mountains before ending along the Adriatic coast, then returning to Kotor. A great distance wasn’t covered, but the variety of scenery was amazing and the driving challenging in places.

Since our first cars as kids, Donna and I have been stick-shift/manual transmission aficionados, with fond memories of the rust bucket Fiats we both drove. We’ve also driven regular sedans up and down rutted, rock strewn dirt roads normally traversed by 4×4 SUVs while being told “you won’t make it in that.”

“Where are you heading to?” “Lovcen National Park will be our first stop.” “Be careful the roads are narrow and there are twenty-one switchback curves on the way. You might want to consider the longer route, it’s more relaxing,” the rental agent cautioned as he assessed our age and abilities. “We understand the views are dramatic along the way,” I responded as he handed over the keys while Donna playfully poked at me for them. Of course, I stalled the car backing out of the parking space, much to the attendant’s secret delight, I think. With a zoom zoom in mind and the windows down, we waved our thank you, only to stall again as we drove away. Hey, it was a high clutch! Some days just start that way.

Whether it’s from the bell tower in Perast or from the top of St. John’s Fortress, it’s impossible to escape glorious views of Kotor Bay once you gain any elevation. Only minutes from old town our route along Montenegro P1, also called the Kotor Serpentine Road, did not disappoint. The question was, how many times would we stop to take photos? Fortunately, there were few other cars on the road that day and we were able to pull over at the switchbacks that had room to park. Harrowing though was encountering large construction trucks and buses barreling downhill towards us, which often required pulling over as far as we could on the already narrow one lane road or reversing downhill to a wider section of paving. To say that guardrails were lacking in many places is an understatement. For centuries, the only overland route into Kotor was the old caravan trail which dates to Roman times. It wasn’t until the 1880s, when Montenegro was part of the Austrian Empire, that an easier wagon route between the seaport of Kotor and mountainous towns of Njeguši and Cetinje was carved from the mountainside. Paved now, that old wagon track was essentially the same route we drove. Eventually we came to a stop behind a local bus which was offloading hikers at Restaurant Nevjesta Jadrana which is the starting point for hiking the old caravan trail downhill into Kotor.

If you are a hairpin-turn fanatic click on this link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DD5u7WKHiYQ for an interesting video of this thrilling drive. And to our surprise it’s on a “most dangerous roads” list!

Warrior, poet, Prince-Bishop and ruler of Montenegro from 1830 to 1851, Petar II Petrovic Njegos captured the essence of Serbian culture and life in several epic poems that put Serbian folk tales and history to verse. “What Shakespeare is to England, Njegos is to Montenegro,” gives a clue to his influence on Serbian culture. In his will he requested Montenegrins bury him in the church on the summit of Mount Lovcen, from which “all the lands of Montenegro can be seen.” On his last days the people lovingly carried him from Kotor to Cetinje, the old capital, along the ancient caravan trail that climbed from Kotor. Interestingly, this act of devotion didn’t seem to be enough, and, perhaps insecure of his legacy, he threatened to curse and haunt them if his last wish was not fulfilled. Ascending the steep stairs to his mausoleum atop the mountain, we understood why he was so insistent in his demand. The 360-degree panoramic view was in so many ways breathtaking. A warm day bayside in Kotor can be extremely chilly on the peak of Mount Lovcen with its 5738 ft elevation, so layer up accordingly. Descending the stairs, we stopped at the appropriately named Lookout Restaurant, which offered delicious local cuisine, very reasonably priced.

Podgorica, the capital city of Montenegro, would be our destination at the end of the day, but before heading that way we detoured over to Lake Skadar National Park. Specifically, to see the beautiful horseshoe bend of Rijeka Crnojevića, the river of Crnojevića, from the Pavlova Strana Viewpoint which from Mount Lovcen is accessed by turning onto a dirt road off the M2.3. (Why the decimal point, really? There’s no 2.1 or 2.9 road that I can see on the map, but I digress.) This was a narrow track that had us wondering if we made the right decision. Our logic seriously questioned again when we reached a stalemate with an oncoming car traveling uphill. The road was so tight I was hesitant to reverse, fearing scraping the car paint and the other driver refused to budge. Somehow the locals know if you are not from around those parts! I blinked first and cautiously backed up until the road was barely wide enough for two cars to squeeze by. Continuing to descend toward the lake, several of the switchback curves were so tight they required 3 point turns to maneuver around the corner. Our persistence though was eventually rewarded with a great view of the river.

Relieved to hit a larger paved road, we continued towards the small village of Crnojevića. The weather was brilliant, and we spontaneously decided to opt for a short boat tour along the river. It was mid-week and near the end of the season, and we were pleased that we had the boat all to ourselves.

It was a relaxing reprieve, silently traveling upon the water, passing under old stone bridges and watching the birds and swans along the water’s edge. Next to the boat launch, Restaurant Mostina offered shaded outdoor dining and a beautiful view of the river. We lingered as long as time allowed, wanting to reach Podgorica well before dark. Fortunately, it was only forty minutes away.

We arrived late in the afternoon and followed our GPS directions into the city and were totally surprised when our route turned into a pedestrian only boulevard after 5 PM, with families pushing strollers down the center of the avenue and waving frantically to make us aware of our mistake. Without difficulty we quickly corrected our error. Having the freedom to roam is wonderful with a rental car, the only drawback really is parking. And finding an affordable, convenient hotel in a city with free parking is a challenge. The three-star, business class Hotel Kerber fit the bill, though finding the parking lot required that the receptionist walk us out the back door and point to the parking entrance under a building on the block behind the hotel.

Exploring the city early the next morning, we walked over the Morača River via the Milenium Bridge, one of the city’s most prominent landmarks. Its futuristic cable-stayed bridge design is so strikingly different from the architecture in the rest of the country.

In the park across the river we found the statue of Vladimir Vysotsky, a beloved Russian poet and songwriter whose verses were deemed subversive by communist authorities and barred from publication. The Bob Dylan of Montenegro, he gained fame by distributing illegal homemade recordings of his songs and performing in clubs across the communist block during the Cold War. Montenegrins loved his music and he loved them. “I regret in this life that I don′t have two roots, and I can′t name Montenegro as my second homeland.” – Vladimir Vysotsky.

The big draw for us to Podgorica was Саборни храм Христовог Васкрсења, the Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ for us non-Serbian speakers. It’s an inspiring new Serbian Orthodox church that was consecrated on October 7th, 2013, the 1700th anniversary of the Edict of Milanin 313 AD, which was an agreement between the Western Roman Emperor Constantine I and the Byzantine Emperor Licinius that decriminalized Christian worship.

Every interior surface of basilica is covered with brilliant Orthodox iconography on gold backgrounds or has controversial murals that reflect history. The one depicting Tito, Marx, and Engels burning in hell is poignant commentary on communism’s oppression and anti-religion stance that affected millions in eastern Europe. There are other contemporary political frescoes interwoven throughout the traditional iconography that are difficult to spot, but that’s part of the thrill of discovery.

To this day, the artist has chosen to remain anonymous. The architect, Dr. Predrag Ristic, is credited with building 100 orthodox churches, and took inspiration for the exterior of the church from the medieval design of the Cathedral of St. Tryphon in Kotor, with its prominent arched entry way and twin towers.

Our destination lunch spot for the day was Restoran Nijagara, located only a short distance before the Vodopad Nijagara waterfall on the Cemi River. The waterfall was beautiful and easily accessible from the shaded, riverside dining on the restaurant’s deck. Ducks floated lazily by while children playfully splashed in the crystal-clear water.

We planned on being along the Adriatic coast for sunset, but still had plenty of time for a stop in the lakeside village of Virpazar, which is a popular point for boat tours of Skadar Lake National Park. The small town had a wonderful ambience with umbrellaed restaurants, streets full of people, colorful boats tied up along its quay. A dramatic memorial to the liberation partisans of WWII anchored the waterfront, with Besac Castle rising above it in the distance. The castle is a short distance from town and has splendid views of Lake Skadar.

We continued along the lake road towards the small historic village of Godinje with its ancient, cojoined stone houses set on the mountainside. The village is unique because each home has an underground passage connecting it to its neighbors. This was developed to defend the village from Ottoman raiders. The tunneling system was so extensive that townspeople could go from one end of the village to the other without being seen by their enemy. There are many small vineyards in this region, featuring wines vinted from the native-to-Montenegro Vranac grape varietal. Some wineries offer tastings along with food. Reservations are highly recommended, especially on the weekends. Unfortunately, we did not have time to linger longer, but we did purchase homemade grape brandy from a woman selling it from a small roadside stand in front of her home.

The views of the Adriatic coastline as we drove north along the E80 were incredible, though there weren’t nearly enough pullover spots for photographs.

We arrived at the Hotel Adrovic in Sveti Stefan with plenty of time to get settled before watching the sunset, with classic Aperol spritzes from their rooftop restaurant.

We put a lot of research into selecting this hotel, primarily for its view of Peninsula Sveti Stefan and it did not disappoint. We enjoyed an incredible ocean view room with a balcony, including breakfast and free parking, for a very reasonable $80.00 per night. Later that night a lively wedding party danced to Montenegrin hits in the restaurant’s banquet room until the early hours of morning.

Budva was an easy twenty-minute drive the next morning. The walled town is one of the oldest cities on the Adriatic coast, dating to the 5th century BC with Illyrian tribes settling the area and later colonization by the Greeks as an important trading port. Its history mirrors Kotor’s with conquest by the Roman empire in the 2nd century BC, followed by the Byzantines, Venetians, Ottoman and Austrian empires all ruling for various lengths of time. And let’s not forget the French, Germans and Russians who settled in for short stays.

The historic, walled old town is much smaller that Kotor, but still fascinating. The town’s fortified walls sit right on the edge of the Adriatic with the tall walls of the citadel rising directly from the sea. The views over church spires of the old town and the coastline were beautiful. It’s from this vantage point that we decided to check out the colorful umbrellas of Mogren Beach across the water. There are actually two pebbled beaches set under towering cliffs separated by a protruding cliff face. Connecting them is a rough tunnel through the rock called the “Door in Stone.”

It was an easy walk along the ocean edge on a paved path with railings, past the Ballet Dancer Statue set on a rock in the water. There is some debate about whether the female figure, sculpted by Gradimir Aleksich, is a dancer or gymnast as she is not clothed, leading some to have nicknamed the bronze statue, “The Girl Who Lost the Swimsuit.” Idealistically he based his graceful creation on the legend of a local young woman who danced on the rocks every day waiting for her fiancé, a sailor, to return from the sea. Years passed, yet she continued to hope for his return, and she danced every day until her death. For the people of Budva the statue represents love, loyalty and fidelity, attributes that have served Montenegrins well through their turbulent history.

Back at our hotel, the sparkling blue waters of the beach below us called. This part of Montenegro’s coast is very steep, but stairs from the hotel weaved down to the ocean far below. Walking down would have been easy. Returning – forget it! The parking lot by the beach was outrageously expensive for a short visit, so we opted to park like the locals, which took some creativity, and found a spot under a heavily laden olive tree. It was the last weekend in October, and the water was still warm enough to swim in.

The tall mountains along the coastline here cast a long shadow over the water at sunrise. We sat quietly on the balcony with the morning’s first cup of coffee and watched the sunlight slowly reveal the red roofs, then warm stone colors of what was once a 15th century island fortress – Sveti Stefan. The small, private islet today is an upscale resort that is connected to the mainland by a small peninsular. It’s an exclusive and dramatic setting, but we had the better view.

On the beach, workers were digging the umbrella anchors out of the sand as others rowed into the ocean to retrieve the string buoys that defined the swimming area. Offshore the crew of a sailboat was pulling anchor in preperation to set sail. It was officially the end of the summer season and time for us to be moving on. We got our swim in just in time.

Till next time, Craig & Donna

Walking, walking, walking! The countryside is full of folks out and about on their feet. There is a rural minibus network connecting larger villages once a day, and Lalibela has tuk-tuks, of course. But mostly, whether it’s due to lack of affordability or availability, people walk to and from everywhere. Sometimes it is necessary to travel great distances to accomplish simple, everyday tasks like gathering water, heading out to tend a remote field, going to market, or even farther to visit a doctor.

Walking, walking, walking! The countryside is full of folks out and about on their feet. There is a rural minibus network connecting larger villages once a day, and Lalibela has tuk-tuks, of course. But mostly, whether it’s due to lack of affordability or availability, people walk to and from everywhere. Sometimes it is necessary to travel great distances to accomplish simple, everyday tasks like gathering water, heading out to tend a remote field, going to market, or even farther to visit a doctor.  In the rugged agrarian highlands surrounding Lalibela, all the fields are tilled by farmers walking behind teams of oxen, as it has been done for centuries, on farmland passed down through a communal hereditary system called rist.

In the rugged agrarian highlands surrounding Lalibela, all the fields are tilled by farmers walking behind teams of oxen, as it has been done for centuries, on farmland passed down through a communal hereditary system called rist.

We started our day listening to bird calls and watching the morning clouds burn off from the valley below our hotel as the sun rose higher into the sky. The

We started our day listening to bird calls and watching the morning clouds burn off from the valley below our hotel as the sun rose higher into the sky. The

The shops were busy, and the roadside Ping-Pong games were in full swing as we departed Lalibela. The road into the mountains rose quickly from Lalibela into a semi-forested landscape. Too steep for crops, the land was used for cattle, which grazed on clumps of wild grasses on the hillside. We stopped at one clearing for the view and noticed a herder gently nudging his cows away from recently planted tree seedlings. “This is part of our government’s commitment to reverse deforestation and help mitigate climate change. It’s called the

The shops were busy, and the roadside Ping-Pong games were in full swing as we departed Lalibela. The road into the mountains rose quickly from Lalibela into a semi-forested landscape. Too steep for crops, the land was used for cattle, which grazed on clumps of wild grasses on the hillside. We stopped at one clearing for the view and noticed a herder gently nudging his cows away from recently planted tree seedlings. “This is part of our government’s commitment to reverse deforestation and help mitigate climate change. It’s called the  “On July 29th Ethiopians planted 350 million trees in a single day, a world record!” he proudly shared. “The farmers know how important this is and help shoo the cattle away, but the government has also chosen a tree seedling that doesn’t taste good.” This annual Ethiopian project is part of the African Union’s

“On July 29th Ethiopians planted 350 million trees in a single day, a world record!” he proudly shared. “The farmers know how important this is and help shoo the cattle away, but the government has also chosen a tree seedling that doesn’t taste good.” This annual Ethiopian project is part of the African Union’s  The road deteriorated after this, with deep mudded ruts tossing us from side to side regardless of how slowly we navigated through, over or around them. Our “rattled tourist syndrome” is the most appropriate way to describe the ride, while optimists might refer to it as an an “African deep tissue massage.” We were the only truck to park at the trailhead to the Asheten Mariam Monastery and were greeted with children selling handicrafts, and young men renting walking sticks and offering to accompany us on the hike.

The road deteriorated after this, with deep mudded ruts tossing us from side to side regardless of how slowly we navigated through, over or around them. Our “rattled tourist syndrome” is the most appropriate way to describe the ride, while optimists might refer to it as an an “African deep tissue massage.” We were the only truck to park at the trailhead to the Asheten Mariam Monastery and were greeted with children selling handicrafts, and young men renting walking sticks and offering to accompany us on the hike. Confident in our abilities we declined, but they tagged along anyway. This was a good thing. What our guide had forgotten to mention was that there was a short steep section at the beginning of the hike, before it leveled off. Within minutes, between the altitude and the terrain, our hearts were pumping and my wife, who struggles with asthma, was gasping for breath. We are unfortunately not the 7 second 0-60mph vroom, vroom of a 1964 Corvette anymore, but more like the putt-putt of a classic Citroën 2CV. We get there, eventually. So, our guide, forgetting his youth and our age, led the way from a distance, as if he was channeling

Confident in our abilities we declined, but they tagged along anyway. This was a good thing. What our guide had forgotten to mention was that there was a short steep section at the beginning of the hike, before it leveled off. Within minutes, between the altitude and the terrain, our hearts were pumping and my wife, who struggles with asthma, was gasping for breath. We are unfortunately not the 7 second 0-60mph vroom, vroom of a 1964 Corvette anymore, but more like the putt-putt of a classic Citroën 2CV. We get there, eventually. So, our guide, forgetting his youth and our age, led the way from a distance, as if he was channeling  It was at this point that my wife spoke up. “Girma, you must think of me as the same age as your mother.” Instantly, his attitude became very solicitous, and he smilingly offered her a hand or other assistance at every opportunity. We marveled at the agility of the local kids. They nimbly scampered up and down the trail, easily outdistancing us, in order to set up their little trailside displays of carvings and beadednecklaces. When we didn’t purchase at first, they simply packed up and reappeared further up the trail. We had to reward such perseverance with a couple of purchases.

It was at this point that my wife spoke up. “Girma, you must think of me as the same age as your mother.” Instantly, his attitude became very solicitous, and he smilingly offered her a hand or other assistance at every opportunity. We marveled at the agility of the local kids. They nimbly scampered up and down the trail, easily outdistancing us, in order to set up their little trailside displays of carvings and beadednecklaces. When we didn’t purchase at first, they simply packed up and reappeared further up the trail. We had to reward such perseverance with a couple of purchases. Meanwhile, we regained our pace as the trail leveled off and tracked along the base of a cliff face that fell away to terraced farmland far below. The incline of the trail continued to rise; the walking sticks were now invaluable in helping us steady our footing on the rough path. Around a curve the trail abruptly narrowed at a sheer rock wall broken by a vertical chasm, slightly wider than our shoulders.

Meanwhile, we regained our pace as the trail leveled off and tracked along the base of a cliff face that fell away to terraced farmland far below. The incline of the trail continued to rise; the walking sticks were now invaluable in helping us steady our footing on the rough path. Around a curve the trail abruptly narrowed at a sheer rock wall broken by a vertical chasm, slightly wider than our shoulders.

Imprinted at the bottom of a page in one ancient text were the thumbprints of the ten scribes who helped copy the book. Legend has it that it was the first church ordered built by King Lalibela during his reign in the twelfth century and that his successor, Na’akueto La’ab, who only ruled for a short time, is buried there.

Imprinted at the bottom of a page in one ancient text were the thumbprints of the ten scribes who helped copy the book. Legend has it that it was the first church ordered built by King Lalibela during his reign in the twelfth century and that his successor, Na’akueto La’ab, who only ruled for a short time, is buried there.

Coming to the end of the road, we could see the monastery dramatically situated behind a small waterfall, in a long shallow cave at the bottom of a cliff.

Coming to the end of the road, we could see the monastery dramatically situated behind a small waterfall, in a long shallow cave at the bottom of a cliff.

Stone bowls smoothed from centuries of use sat in various places on the rough floor to collect the water seeping from the cave’s ceiling one drip at a time. It gets blessed by the priest and used as Holy water, continuing a tradition from the 12th century when King La’ab ordered the monastery’s creation.

Stone bowls smoothed from centuries of use sat in various places on the rough floor to collect the water seeping from the cave’s ceiling one drip at a time. It gets blessed by the priest and used as Holy water, continuing a tradition from the 12th century when King La’ab ordered the monastery’s creation.

In the learning area, layers of carpet attempted to smooth an uneven, rocky floor where the novitiates sit to learn the ways of the orthodox church. In the corner rested several large ceremonial drums used during worship services. Picking one up our guide beat out a rhythm that would normally accompany liturgical chanting, or Zema, by the young monks. We’ve noticed that the treasures of the Ethiopian churches are not determined by their monetary value and locked securely away, only to be used on religious holidays, but by their spiritual connection. Precious, irreplaceable, ancient bibles and manuscripts, lovingly worn and torn as they are, continue to be used every day, as they have been for the last nine-hundred-years.

In the learning area, layers of carpet attempted to smooth an uneven, rocky floor where the novitiates sit to learn the ways of the orthodox church. In the corner rested several large ceremonial drums used during worship services. Picking one up our guide beat out a rhythm that would normally accompany liturgical chanting, or Zema, by the young monks. We’ve noticed that the treasures of the Ethiopian churches are not determined by their monetary value and locked securely away, only to be used on religious holidays, but by their spiritual connection. Precious, irreplaceable, ancient bibles and manuscripts, lovingly worn and torn as they are, continue to be used every day, as they have been for the last nine-hundred-years. It is well worth the effort to visit these remote churches and monasteries. The physical strength required and hardships endured to build these remote churches as a testament of faith continues to be inspiring.

It is well worth the effort to visit these remote churches and monasteries. The physical strength required and hardships endured to build these remote churches as a testament of faith continues to be inspiring.

Often overshadowed in recent decades by its East African neighbors recognized for their safaris, Ethiopia has been known to Western culture for millennia. It was first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, around 1000 BC (3,000 years ago!), when the Queen of Sheba, hearing of “Solomon’s great wisdom and the glory of his kingdom,” journeyed from Ethiopia with a caravan of treasure as tribute. Unbeknownst to Solomon their union produced a son, Menilek, (meaning son of the wise man). Years later, wearing a signet ring given to him by his mother, Menilek visited Jerusalem to meet Solomon and stayed for several years to study Hebrew. When his son desired to return home, Solomon gifted the Ark of the Covenant to Menilek for safe keeping in Ethiopia, and to this day it is said to reside in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, in Aksum, where only a select few of the Ethiopian Orthodox church can see it.

Often overshadowed in recent decades by its East African neighbors recognized for their safaris, Ethiopia has been known to Western culture for millennia. It was first mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, around 1000 BC (3,000 years ago!), when the Queen of Sheba, hearing of “Solomon’s great wisdom and the glory of his kingdom,” journeyed from Ethiopia with a caravan of treasure as tribute. Unbeknownst to Solomon their union produced a son, Menilek, (meaning son of the wise man). Years later, wearing a signet ring given to him by his mother, Menilek visited Jerusalem to meet Solomon and stayed for several years to study Hebrew. When his son desired to return home, Solomon gifted the Ark of the Covenant to Menilek for safe keeping in Ethiopia, and to this day it is said to reside in the Church of Our Lady Mary of Zion, in Aksum, where only a select few of the Ethiopian Orthodox church can see it.

With the Ethiopian Orthodox Church having a site in Jerusalem since the sixth century, Ethiopian pilgrimages to the Holy Land, which took six months, were common until the route was blocked by Muslim conquests in 1100s and the journey became too hazardous. As it became surrounded further by Muslim territories, the country sank into isolation from Europe. Ethiopia’s early history and its connection to Judaism and Christianity is a twisting tale, like caravan tracks across the desert, meeting then disappearing behind sand dunes, the story buried by the blowing sands of time.

With the Ethiopian Orthodox Church having a site in Jerusalem since the sixth century, Ethiopian pilgrimages to the Holy Land, which took six months, were common until the route was blocked by Muslim conquests in 1100s and the journey became too hazardous. As it became surrounded further by Muslim territories, the country sank into isolation from Europe. Ethiopia’s early history and its connection to Judaism and Christianity is a twisting tale, like caravan tracks across the desert, meeting then disappearing behind sand dunes, the story buried by the blowing sands of time. Distraught by this, King Lalibela commissioned eleven architecturally perfect churches, to be hewn from solid rock, to serve as a New Jerusalem complete with a River Jordan for pilgrims to visit. He based the designs on memories of holy sites from his own pilgrimage to the Holy Land as a young man.

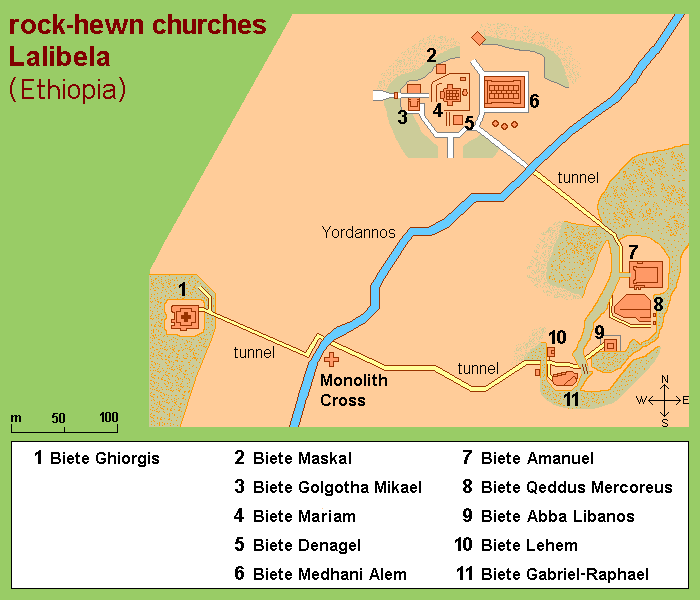

Distraught by this, King Lalibela commissioned eleven architecturally perfect churches, to be hewn from solid rock, to serve as a New Jerusalem complete with a River Jordan for pilgrims to visit. He based the designs on memories of holy sites from his own pilgrimage to the Holy Land as a young man. Considering the limited availability of tools in the 1100s, I can’t imagine what a daunting task this must have been. I’m sure the chief architect said, “you have to be kidding.” It’s believed that 40,000 men, assisted by angels at night, labored for 24 years to create this testament to their faith. Masons outlined the shape of these churches on top of monolithic rocks, then excavated straight down forty feet to create a courtyard around this solid block. Doors would then be chiseled into the block and the creation of the church would continue from the inside, often in near total darkness.

Considering the limited availability of tools in the 1100s, I can’t imagine what a daunting task this must have been. I’m sure the chief architect said, “you have to be kidding.” It’s believed that 40,000 men, assisted by angels at night, labored for 24 years to create this testament to their faith. Masons outlined the shape of these churches on top of monolithic rocks, then excavated straight down forty feet to create a courtyard around this solid block. Doors would then be chiseled into the block and the creation of the church would continue from the inside, often in near total darkness.

Women worshippers traditionally enter through a separate door and pray apart from the men. Inside, thirty-eight stone columns form four aisles and support a stone ceiling that soars overhead. After walking for days or weeks to reach Lalibela, often fasting the entire time, the journey ends here for many pilgrims, in hopes of receiving a blessing or cure from touching the Lalibela Cross and offering prayers.

Women worshippers traditionally enter through a separate door and pray apart from the men. Inside, thirty-eight stone columns form four aisles and support a stone ceiling that soars overhead. After walking for days or weeks to reach Lalibela, often fasting the entire time, the journey ends here for many pilgrims, in hopes of receiving a blessing or cure from touching the Lalibela Cross and offering prayers.

The next morning, we completed our tour of the cluster of the southern of the rock churches: Beta Emmanuel (Church of Emmanuel), Beta Abba Libanos (Church of Father Libanos), Beta Merkurios (Church of Mercurius) and Beta Gabriel and Beta Rafa’el (the twin churches of Gabriel and Raphael.)

The next morning, we completed our tour of the cluster of the southern of the rock churches: Beta Emmanuel (Church of Emmanuel), Beta Abba Libanos (Church of Father Libanos), Beta Merkurios (Church of Mercurius) and Beta Gabriel and Beta Rafa’el (the twin churches of Gabriel and Raphael.)

It’s important to remember that this is not a museum with ancient artifacts and manuscripts in glass cases, but an active holy site where the ancient manuscripts are still used daily, and it is home to a large community of priests and nuns. It has been a destination for Ethiopian Orthodox pilgrims in the northern highlands (elevation 8,200’) for the last 900 years and continues to be visited by tens of thousands of pilgrims annually.

It’s important to remember that this is not a museum with ancient artifacts and manuscripts in glass cases, but an active holy site where the ancient manuscripts are still used daily, and it is home to a large community of priests and nuns. It has been a destination for Ethiopian Orthodox pilgrims in the northern highlands (elevation 8,200’) for the last 900 years and continues to be visited by tens of thousands of pilgrims annually. Leaving the churches behind, we walked through an area of ancient two story, round houses called Lasta Tukuls, or bee huts, built from local, quarried red stone. Abandoned now for preservation, they looked sturdy, their stone construction distinctive from the other homes in the area that use an adobe method.

Leaving the churches behind, we walked through an area of ancient two story, round houses called Lasta Tukuls, or bee huts, built from local, quarried red stone. Abandoned now for preservation, they looked sturdy, their stone construction distinctive from the other homes in the area that use an adobe method. Today roughly 100,000 foreign tourists, in addition to Ethiopian pilgrims, visit Lalibela annually, a far cry from its near obscurity 140 years ago. Located four hundred miles from Addis Ababa, it is still far enough off the usual tourist circuits to make it a unique and inspiring destination.

Today roughly 100,000 foreign tourists, in addition to Ethiopian pilgrims, visit Lalibela annually, a far cry from its near obscurity 140 years ago. Located four hundred miles from Addis Ababa, it is still far enough off the usual tourist circuits to make it a unique and inspiring destination.

We would have been terribly dissappointed if this had happened to us and we missed visiting the Mursi tribe. (Note to self – don’t leave important events to the last day.) Curious children made their way amidst the tourist vehicles, looking through the windows and asking for soap, shampoo, pens, pencils, caramels, and empty water bottles. The kids would have been happy with anything anyone gave them. Some pointed to the clothes we were wearing, hoping we would donate them. Folks make do with very little here and wear things until they are threadbare, out of necessity. Often, we saw older children wearing infant onesies with the feet of the garment cut off. We are not criticizing; it’s all they had. It saddened us and we wished we had brought an extra suitcase of clothes along to donate to a village. Eventually there was a burst of activity with rumbling engines at the front of the line and folks running back to their rides.

We would have been terribly dissappointed if this had happened to us and we missed visiting the Mursi tribe. (Note to self – don’t leave important events to the last day.) Curious children made their way amidst the tourist vehicles, looking through the windows and asking for soap, shampoo, pens, pencils, caramels, and empty water bottles. The kids would have been happy with anything anyone gave them. Some pointed to the clothes we were wearing, hoping we would donate them. Folks make do with very little here and wear things until they are threadbare, out of necessity. Often, we saw older children wearing infant onesies with the feet of the garment cut off. We are not criticizing; it’s all they had. It saddened us and we wished we had brought an extra suitcase of clothes along to donate to a village. Eventually there was a burst of activity with rumbling engines at the front of the line and folks running back to their rides.  We were the third car in a group of five that was being led by a pickup truck full of armed paramilitary policemen. Many of the incidents that have occurred are related to the increase in truck and bus traffic roaring through Mursi territory on the way to new cotton and sugarcane plantations along the banks of the Omo River.

We were the third car in a group of five that was being led by a pickup truck full of armed paramilitary policemen. Many of the incidents that have occurred are related to the increase in truck and bus traffic roaring through Mursi territory on the way to new cotton and sugarcane plantations along the banks of the Omo River.  Cattle are very often herded down the roads and sometimes are struck and killed, along with their herders. Often drivers do not stop to take responsibility. In the eyes of the villagers, the local authorities have not resolved the situation. As a result, tribespeople will set roadblocks to rob buses carrying plantation workers and extract revenge on truckers. A while later we stopped and were assigned an armed escort, with an AK-47, who accompanied us for the duration of our visit. He was euphemistically called a scout.

Cattle are very often herded down the roads and sometimes are struck and killed, along with their herders. Often drivers do not stop to take responsibility. In the eyes of the villagers, the local authorities have not resolved the situation. As a result, tribespeople will set roadblocks to rob buses carrying plantation workers and extract revenge on truckers. A while later we stopped and were assigned an armed escort, with an AK-47, who accompanied us for the duration of our visit. He was euphemistically called a scout. Turning off the dirt road, branches scratched against the side of the truck as we followed a narrow dirt track through the savanna to a clearing where a small group of thatched huts stood. Soon the women of the village stopped what they were doing to greet us.

Turning off the dirt road, branches scratched against the side of the truck as we followed a narrow dirt track through the savanna to a clearing where a small group of thatched huts stood. Soon the women of the village stopped what they were doing to greet us.

It was a steep walk up a trail through a forest of false banana, enset, to a well-kept sturdy hut with a medicinal herb garden.

It was a steep walk up a trail through a forest of false banana, enset, to a well-kept sturdy hut with a medicinal herb garden.  Outside two women were pinching clay into bowls and teapots that would later be sold at a weekly market.

Outside two women were pinching clay into bowls and teapots that would later be sold at a weekly market.

With sunlight shining through a canopy of giant enset leaves above her, a tribeswoman prepared kocho, a traditional Ethiopian flatbread, over an open smoky fire as we sat and watched. Behind us children giggled as they playfully rolled an old bicycle rim down the path.

With sunlight shining through a canopy of giant enset leaves above her, a tribeswoman prepared kocho, a traditional Ethiopian flatbread, over an open smoky fire as we sat and watched. Behind us children giggled as they playfully rolled an old bicycle rim down the path.

There was a lively commotion of activity by the buses as porters brought over bundles to be tossed up onto the roofs and tied down before heading back to outlying villages.

There was a lively commotion of activity by the buses as porters brought over bundles to be tossed up onto the roofs and tied down before heading back to outlying villages.  Goats, cows and children were left to wander about freely while small piles of detritus burned slowly in the streets as vendors cleaned up at the end of the day. The earthy smell of dung and smoke lightly scented the air. It was chaotic.

Goats, cows and children were left to wander about freely while small piles of detritus burned slowly in the streets as vendors cleaned up at the end of the day. The earthy smell of dung and smoke lightly scented the air. It was chaotic.