First Impression: Madrid is monumental! The minute we exited the Puerta de Atocha train station onto the sidewalk, we were struck by the beauty of the wide boulevards lined with stately trees and grand architecture, and the top of buildings graced with colossal sculptures of mythic gods.

If the Paseo del Prado, the route to our hotel, could speak, it would surely boast of its famous destinations along its length: Madrid’s Museum Triangle, which includes the Reina Sofia Museum where Picasso’s Guernica hangs; the Prado Museum, which highlights the works of Diego Velázquez and Goya; as well as the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, which displays 13th-20th-century European masterpieces. But its bragging rights continue with the Real Jardín Botánico, the Museo Naval with its fascinating exhibits devoted to Spanish maritime history, The Glory and Pegasus sculptures atop the Ministry of Agriculture, and the famous fountain depicting the goddess Cybele’s chariot being pulled by two lions. This relatively short distance is packed with so many highlights it should be called Madrid’s marvelous mile.

Our hotel the Apart-Hotel Serrano Recoletos was just a few blocks from the iconic Cibeles Fountain, which is centered in a traffic circle you usually have to observe from a distance, but overnight the Paseo del Prado was transformed into the festive final leg of the Movistar Half Marathon, with the finish line down the street from our hotel.

With the majestic boulevard closed to traffic, folks were free to wander up to the fountain for a close view, an accessibility that rarely happens. Yesterday we hadn’t realized the median strip that runs the length of Paseo del Prado was lavishly planted with gardens and as luck would have it, the tulips and flowering trees were in bloom. Heading towards the historic center of Madrid, we observed a large group of healthcare professionals marching peacefully down the Gran Via protesting government policies. It was a busy Spring Sunday in Madrid.

Plaza Mayor, ground zero for the historic center of Madrid, was our destination. Once the ancient city’s market area, the area was transformed by architect Juan Gómez de Mora during Philip III’s reign in 1617, and of course the King is dutifully recognized, gallantly astride an equestrian statue in the plaza’s center.

The vision of three successive architects contributed to the plaza as seen today, the result of three devasting fires in 1631, 1670 and 1790. Over the centuries it has hosted bullfights, executions during the Inquisition, Royal wedding celebrations, soccer games and Christmas markets. As an exclusive address in Madrid, many of the apartments are passed down within the same families from generation to generation.

Plaza Mayor gets hectic, but tucked away under the arcaded sidewalk, there are some hidden gems worth finding. Our favorite was La Torre del Oro. It’s an old atmospheric bar dedicated to celebrating Spain’s bullfighting traditions.

There are so many interesting destinations centered around this plaza that we often started our days here as a way to get oriented in old Madrid’s labyrinth of alleys. Treating the nine ancient gateways into the plaza as compass points, we would follow their direction into the surrounding barrios.

Our wanderings to soak up the ambience of this ancient quarter were frequently determined by a list of restaurants and cafes, along with historic sites and churches, we hoped to find. The choices were overwhelming. Since this was our first time in Madrid, we hit many of the tried-and-true spots, like Chocolatería San Ginés, famous for serving Madrileños the best hot chocolate with churros for over 125 years. There was a fast-moving queue when we arrived before 11, which suddenly evaporated and freed sidewalk tables, but it was much more interesting before the lull in activity. And El Riojano, a renowned 19th-century Pastelería with a tantalizing spinning tower of sweet temptations in its storefront window, is sure to break the will of any dieter. When you first enter, it looks like there are not any tables to sit at, but next to one of their display cases there is an opening into a large, popular back room for café. We are after all tourists.

One late afternoon by the El Oso y el Madroño sculpture, a band of buskers filled the Puerta del Sol with music. The Bear and the Strawberry Tree is a medieval heraldic emblem that has been associated with Madrid since 1222, when King Alfonso VIII used the image on a stamp to seal a royal decree.

We continued past the Plaza Mayor towards the Plaza de la Armería, where the Catedral de la Almudena, (1883), and the Royal Palace of Madrid (1738), face each other. Turning onto Calle del Factor, we walked a short distance uphill to the Jardín de Larra and joined a small group of folks waiting to enjoy the sunset.

Afterwards at the bottom of the street we entered the Iglesia Catedral de las Fuerzas Armadas. It’s a small 17th century church dedicated to the Spanish armed forces. The church’s simple façade conceals a lavish marble interior with several interesting altars depicting paternalistic colonial themes.

The streets of Madrid seem even busier at night with folks bustling about after work. On the way back to our hotel, we stopped at the Mercado de San Miguel, one of Madrid’s old, covered food markets, which dates from 1916. Today it’s a gentrified, popular gastronomic destination, with tapas, tapas, and more tapas to satisfy everyone’s tastes.

Madrid’s iconic Tio Pepe neon sign blazed brightly above the Puerta del Sol, and shops along the plaza brilliantly displayed their merchandise in dramatically lighted storefront windows. While Madrid exudes ambience during the day, the city becomes magical in the evenings.

Dinner was at La Casa del Abuelo CRUZ, a traditional tapas bar that has been run by the same family since 1906. Their specialty, gambas al ajillo (sizzling garlic prawns), while very delicous, was a terrible value for the portion size. Their vino de casa, an excellent strong red wine, was memorable and eased the pain of the excessive bill.

Spain’s empire building and wealth followed Columbus’ discovery of the Americas in 1492. A daring nautical leap of faith at the time, it set in motion an era of exploration by sea, that would expand the Spanish Empire around the globe. With that in mind, and an interest in boats, we headed to the Museo Naval on Paseo del Prado, near the Prado Museum. It’s a wonderful museum with exhibits in chronological order, which highlight exquisite ship models, nautical instruments, maps, weaponry, and paintings depicting important naval battles. The exhibits include models of the Niña, Pinta, and Santa Maria which composed Columbus’ small fleet on his epic first voyage.

Afterwards we headed into the centro historico for lunch at Casa Toni, an intimate, no-frills bar, that serves tasty seafood and offal tapas. A short line had formed for tables by the time we arrived, but it moved quickly, especially if you opted for a table upstairs, though downstairs is where all the action is with other folks, jammed into a small space, standing at the bar, and seated at some very tiny tables. It’s a friendly boisterous spot. Pig ears and fried lamb lungs might not be for everyone, but they were surprisingly very tasty.

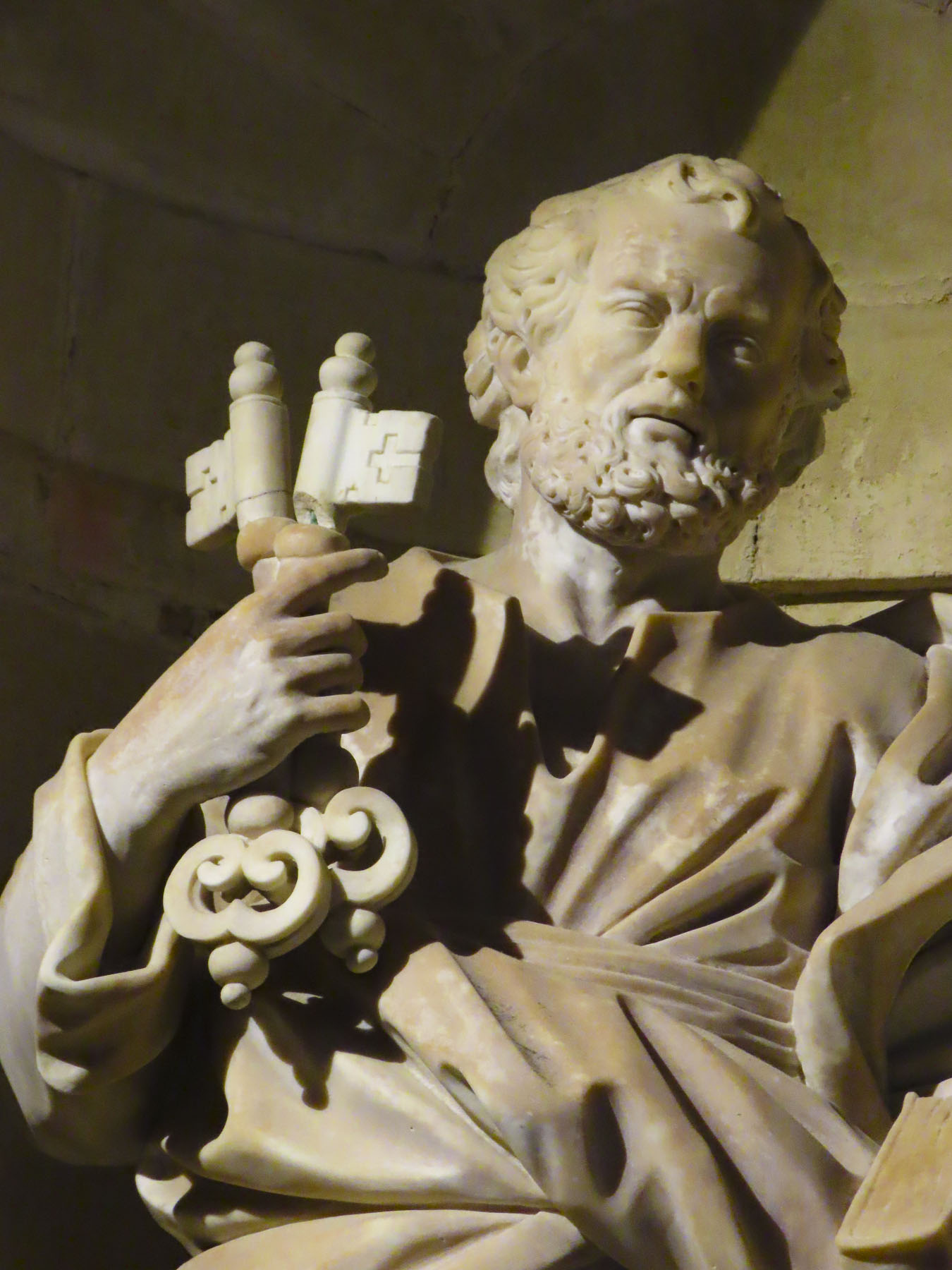

Gold and silver from the Americas fueled church building across Spain in the 16th – 18th centuries.While it’s possible to enjoy Madrid without visiting any churches, we’ve developed a policy of going inside if the door was open. It nicely slowed down our day and transported us back to a time when amazing buildings were constructed only using hand tools to carve stone and shape wood. And the religious paintings and iconography, while they might not be of interest to everyone, display a level of craftsmanship and imagination that’s worthy of appreciation. Unfortunately, the churches were also vast repositories of riches, donated by the wealthy and poor alike, to secure a place in heaven.

Near the San Miguel market, down from the Plaza de la Villa, on Calle de Puñonrostro, we happened upon the inconspicuous entrance to the small chapel at the Monastery of Corpus Christi las Carboneras, that dates from the early 1600s. It’s a tall, narrow, petite sanctuary. When we were turning to leave, I noticed on the second level the privacy screen across the prayer area for the sequestered nuns. It didn’t actually offer much privacy since a I spotted a seated nun watching the tourists in the chapel. I waved gently, she smiled and waved discreetly back.

A door further along the calle leading to the convent’s dulces turno was just being locked; I could hear the click, a few minutes shy of their posted hours. The dulce turnos are a centuries-old tradition that has remarkably survived in convents across modern Spain, as a means for nuns to support themselves. The turno is essentially a lazy-susan style cabinet with doors on both sides of the wall that lets the customers purchase cookies and other baked cooked from the sequestered nuns while still maintaining the nuns’ privacy. Cookie orders are spoken through the wall. If your Spanish is insufficient, it’s handy to write out what you’d like. There is usually a list of what’s available taped to the door of the cabinets. You place your money on the shelf, the wheel turns, and cookies appear as if by magic. It’s delightful! At the bottom of the street, in front of a public library, stands a bronze statue of a man. It’s named El Lector, the reader, a tribute to Carlos Cambronero, a writer devoted to Madrid’s history. Across the street the unusual convex, baroque facade of the Basílica Pontificia de San Miguel (1739) intrigued us, and we explored more inside.

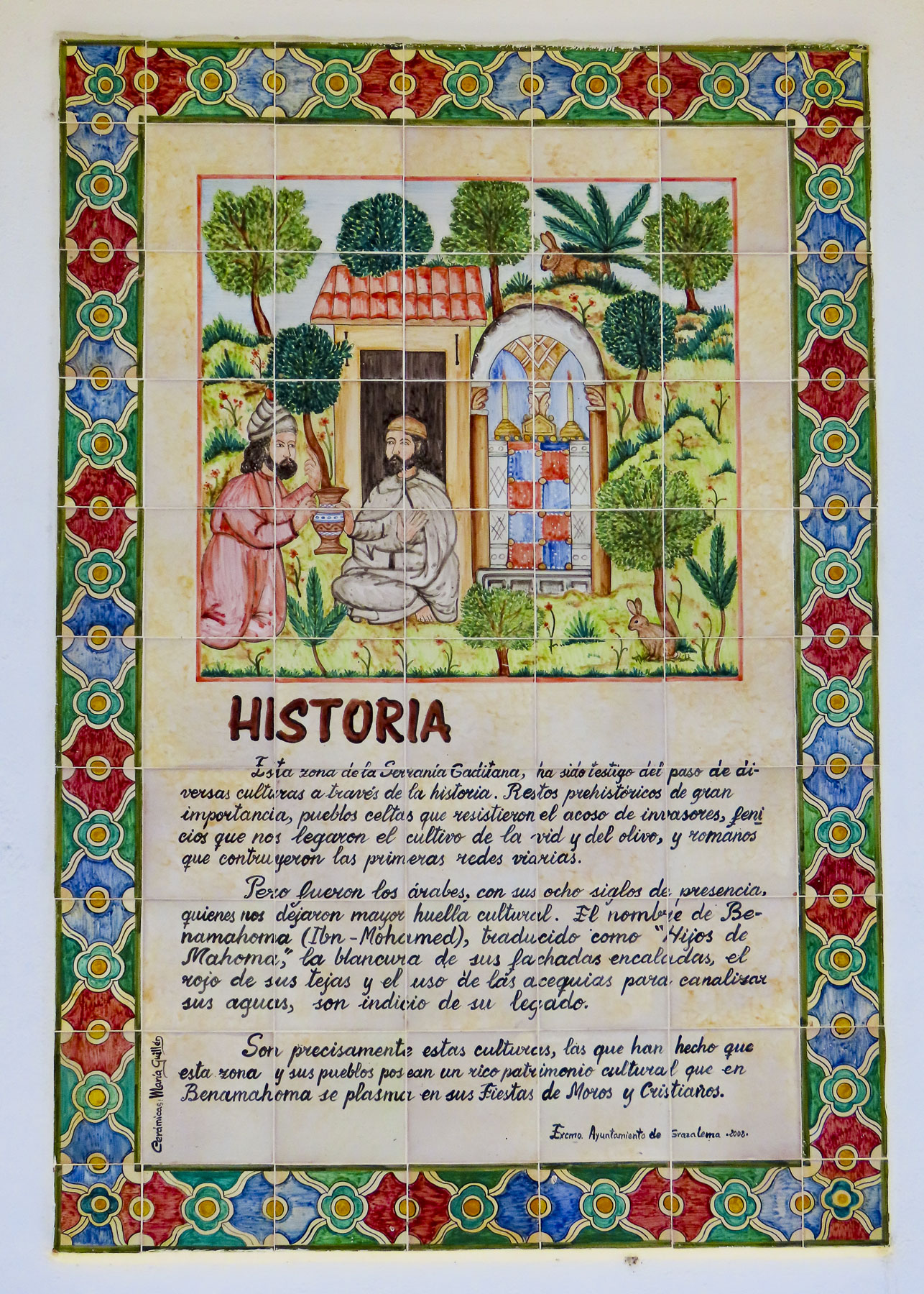

The calles go every which way in La Latina, one of Madrid’s oldest areas, where the narrow streets and plazas follow the original 9th century footprint of the Arab citadel that originally stood there. Though its buildings might be old, the area now attracts a vibrant young crowd that enjoys an immense collection of tapas bars and restaurants along Cava Baja and Cava Alta. The two nearly parallel streets have been popular since medieval times, when traveling merchants stayed at inns and taverns along the calles, and used tunnels or access holes dug at the end of the streets to enter the walled city at night when the gates were closed.

At the end of Cava Baja and Cava Alta, the colorful Mercado de la Cebada, with its distinctive wavy roof, is a modern architectural dichotomy in its surroundings. The shopping in this mercado is an authentic Madrileño experience that is not touristy at all.

From the entrance to the market, we noticed the tall silhouette of the Royal Basilica of Saint Francis the Great’s large dome, several blocks away, dominating the neighborhood, and decided to check it out.

This is a mammoth, mid-18th century cathedral designed in the Neoclassic style, the size of which we did not fully realize until we were standing under its 108-foot-wide and 190-foot-high dome. Legend believes that St. Francis chose this site himself when he visited Madrid in 1214 during his pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela. The dome is the largest in Spain and the fourth largest in Europe. It was breathtaking in scale and equally fascinating with celestial frescos by Casto Plasencia Mayor decorating the cupola, and paintings behind the altar by Manuel Dominquez and Alejandero Ferrant, illuminating biblical stories.

Six smaller but equally opulent chapels in several different architectural styles, from Baroque to Byzantine, and Renaissance to Rococo, ring the main altar, each mini museum displaying a wealth of religious art created by the Spanish masters Francisco José de Goya, Alonso Cano, Francisco Zurbarán, Antonio González Velazquez, José Moreno Carbonero, and others. This church is one of the most beautiful we’ve visited in Spain and should be on everyone’s “must do in Madrid,” lists.

Afterwards, on Carrera de San Francisco, 14, as we started our return leg to our hotel, we happened upon two very good gastronomic discoveries. The artisanal bakery, Obrador San Francisco, was full of the wonderful aroma from fresh baked bread that was just being put out for purchase. And of course, to go along with good bread, you need good cheese. This was accomplished easily enough, right next door, at Quesería Cultivo, a cheese shop, with an amazing array of Iberian cheeses. It’s worth stopping here just for the earthy aroma that greets you when you enter the store, an experience that will have you picturing idyllic Spanish mountain pastures, full of grass-grazing and milk-producing livestock.

Being the cheese aficionados that we are, we had one more stop in mind, at Casa González. They have been selling cheese in Madrid since 1931 and have slowly expanded to become a petite gourmet shop and small bar with a handful of tables, where they are happy to advise you on which wines to pair with each cheese.

On our last full day in Madrid, we wandered the exhibition galleries at the Prado, viewing the museum’s vast collection of classical European art, which spans from the sixth century BC until the late 19th century. We especially enjoyed the works of Goya, Velázquez, and El Greco. Goya created over 700 paintings during his lifetime and embraced many different themes from royal portraiture, to Romanticism, to religious art, and later his dark paintings, toward the end of his life.

Around the corner from the museum, we lunched at Plenti, which served delicious and inexpensive food. We spent the rest of the afternoon exploring Real Jardín Botánico, where many of its plantings were just beginning to flower.

In El Retiro Park we did the classic tourist stuff, visiting the Palacio de Cristal, originally built as an exposition greenhouse, but now hosting art exhibits, and the Monument to Alfonso XII on the El Retiro boating pond. Interestingly, the park was originally created in 1630 as an exclusive sanctuary for Spanish Kings and members of the royal court, and famous naval battles were re-enacted on the boating pond for the monarchy’s entertainment.

The large 350-acre treed park, with manicured gardens, fountains and monuments was perfect for royal courtships and discreet liaisons. It was gifted by the monarchy to Madrid and permanently opened to the public in 1868, a much-needed addition to the city’s greenspace at the time.

The sun was warm for late March and folks were out and about, enjoying life. It was a perfect day.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna

Please share my page with your friends