Taillights glistened on the rain-slicked roadway as we followed a tram through the Friday evening rush-hour in Zagreb, the capital of Croatia. It’s a large metropolis with newer neighborhoods spiderwebbing for miles from its ancient medieval core atop Gornji Grad, the Upper Town. We were heading to Hotel Park 45, conveniently located near the old town, with the availability of reserved paid parking. It was the base for our three-night stay in the Croatian capital.

Deterred by the rain from venturing too far from the hotel that night, we found the Evergreen Sushi Bar, several doors down. The restaurant was nicely designed in a casual modern Asian theme. The sushi we ordered was very good and the evening was enhanced with the theatrical presentation of some of the dinners which flowed from the kitchen. It was a nice change from the traditional Balkan fare which we had been indulging in.

The next morning, we enjoyed the ambiance of the Lower Town’s old buildings as we slowly strolled past the earthen tones of 19th-century Austro-Hungarian architecture. Some had interesting embellishments but had been allowed to deteriorate, and we were pleased to see renovations beginning on these beautiful structures. Our destination was Gornji Grad, and we turned to follow Mesnička ul, a long xsteep street to the Old Town.

Eighty decades earlier, halfway up the hill, the Croatian government at the time excavated the Tunel Grič during World War II, as a bomb shelter for its citizens. The war ended shortly after its completion and the tunnel was used as a warehouse for many years before being closed and forgotten until it was needed once again to shelter the populace during the Croatian War of Independence in the 1990s. Fortunately for us, after extensive renovations the 350m (1,150ft) long tunnel was reopened in 2016 as a pedestrian passageway and shortcut between the upper and lower town, which saved us from an otherwise strenuous uphill trek to Gornji Grad. Throughout the year the tunnel is also used to host events and art installations. Its most notable transfiguration is during the Christmas holiday season when the tunnel is turned into an enchanting winter wonderland.

At the far end the tunnel opened to Ul. Pavla Radića, a charming, historic cobblestone lane that was for centuries the primary connection between the lower and upper towns. Today it’s lined with shops, cafes and galleries as it runs downhill to Trg bana Josipa Jelačića, Zagreb’s central square or uphill, the direction we were going, to Kamenita Vrata, Gornji Grad’s old stone gate. An equestrian statue of Saint George guarded the entrance to the Upper Town, across from pastel toned buildings, which were a nice change from the ubiquitous sandstone facades.

Kamenita Vrata is Zagreb’s last surviving Medieval stone gate. Its construction was started in the mid-1240s after the first Mongol invasion by the army of Great Khan Ögedei, the third son of Genghis Khan; his campaign left a swath of destruction across the Balkans, and Zagreb in ruins.

Within the gateway is an actively used shrine to the Virgin Mary. Legend believes the shrine’s painting was found miraculously untouched in the tower’s ashes after Zagreb’s Great Fire of 1731. The icon has become a symbol of the city’s resilience, and a popular spot for contemplation and candle lighting, surrounded by marble plaques hanging on the walls offering thanksgiving to Mary for answering folks’ prayers.

Through the gate we wondered along to Plato Gradec, a small plaza with murals and a view of 14th century Zagrebačka Katedrala, Cathedral of Zagreb, which was wrapped in construction scaffolding as it undergoes a multi-year renovation to repair structural damage it suffered during the 2020 5.5-magnitude earthquake that struck the region 140 years after an 1880 quake damaged it significantly. The first flowers of spring were blooming in a sheltered patch of sunlight.

From here we walked to the Love Rails, a romantic spot that overlooks the Lower Town, and where couples symbolize their commitment to each other by attaching love locks. Lower on the hillside are the Zakmardi Steps, a colorful graffiti-lined narrow alley, that leads to Ul. Pavla Radića street or the funicular station. Instead, we chose to follow the tree shaded Strossmayer Promenade, a charming historic walkway, built with public donations, atop the foundations of the Upper Town’s old defensive ramparts in the mid19th-century. It is named for the influential Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer, who served the people of Croatia for 55 years, and was admired for “the unwavering loyalty and affection he demonstrated for his people despite encountering significant opposition from both the Pope and the Austrian Emperor.”

Nearby was Lotrščak Tower, as old as the Stone Gate; it gets its name from its medieval “thieves’ bell,” which rang every night to announce its closing until sunrise the next day. The tower was spared during the demolition of the citadel’s ramparts in the 18th and 19th centuries, as the town expanded. Originally shorter, additional floors were added to the tower in the late 1800s. In 1877, the Grič Cannon, a signal cannon, was fired from the tower for the first time to mark high noon. The city’s bellringers synchronized with the cannon in order to ring the church chimes at the proper moment later in the day. It’s a long-standing tradition that still continues.

The climb to the top started across from an exterior residential staircase, artfully lined with colored pots, before entering the third and fourth floors which showcase historical photographs of the city, hung on the tower’s nearly 1.2m (4ft) thick walls and the Grič Cannon. If you are scared of heights, windows on these levels offer safe vantage points for views over the city instead of continuing the climb up the old spiral staircase to the polygonal shaped fire observation tower and its catwalk. The catwalk was quite jammed when we visited, but the panoramic views over old Zagreb and its modern skyline dotted with construction cranes were fantastic.

It’s from here that the iconic photos of St. Mark’s Church’s tiled roof are taken, with the medieval coat of arms of the Triune Kingdom of Croatia, Dalmatia, and Slavonia and the City of Zagreb. Though the Gothic styled church dates from the 13th-century, it did not get its colorful tile roof until a major renovation in the 1880s. We had hoped to photograph Zagreb’s funicular, the world’s shortest public funicular, connecting the Lower and Upper Towns in a quick 64-second, 66m (217ft) ride, that has been operating since 1890, but it was undergoing repairs.

On opposite sides of the street as we headed to the church were two interesting museums, the Museum of Broken Relationships, and Croatian Museum of Naïve Art. Both have small exhibition spaces, but the former has a quirky collection of heartbreak stories and symbolic possessions from past loves that people from around the world have donated to the museum. A lot of reading is required to navigate through this literary journey of lost love, where many of the stories echo true. The museum also has an excellent café on site.

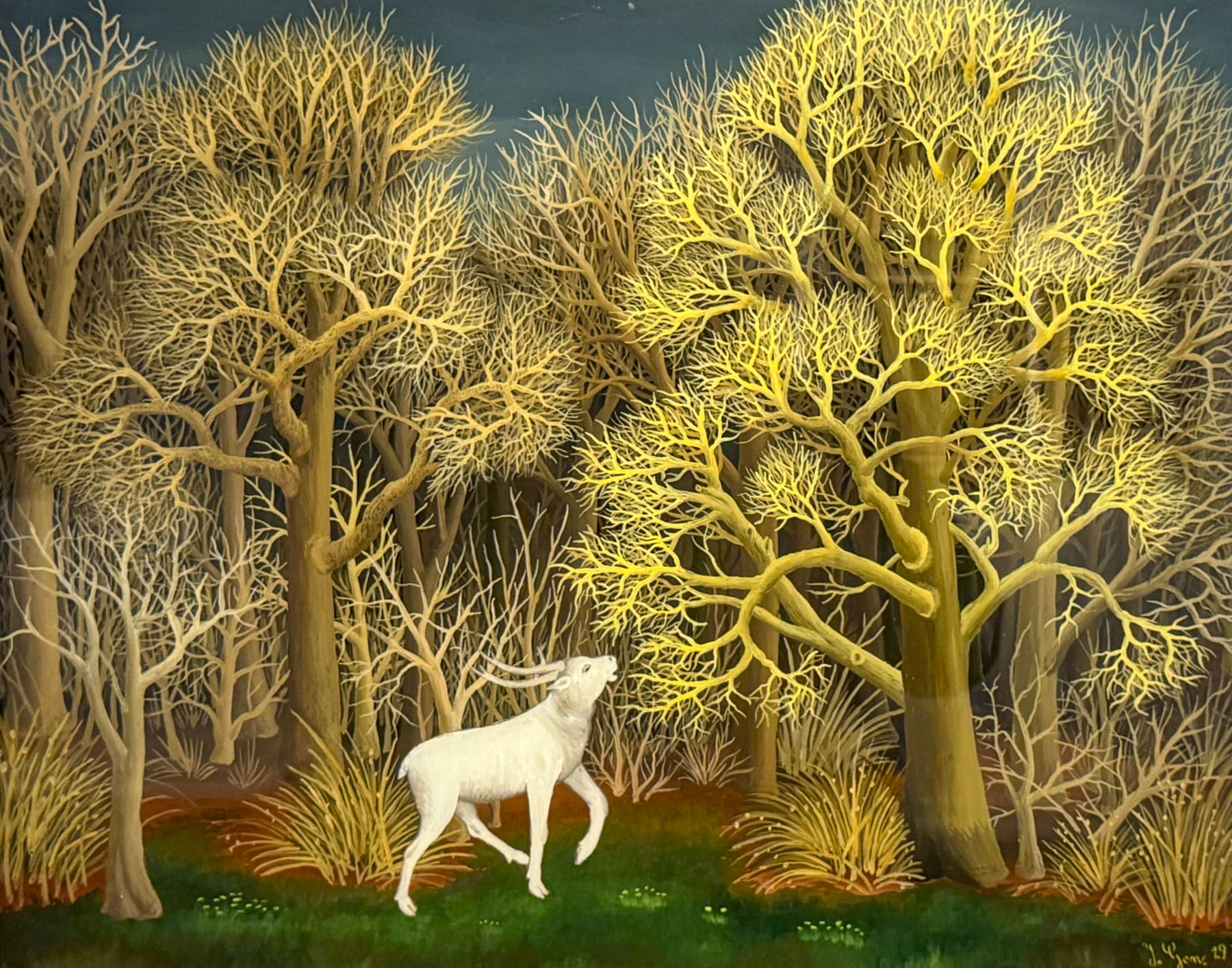

The latter museum has a unique collection of art from self-taught painters from the rural village of Hlebine. The villagers were inspired by Krsto Hegedušić, a native son who was academically trained as a painter, illustrator and theatrical designer, but returned to his family’s village every year and inspired several villagers in the 1930s to paint “what they see and feel.”

They went on to create a body of work that depicted rural life, portraying the hardships of labor and social injustice, along with often mystical landscapes. Many of the oil paintings are reverse painted on glass, a fragile but inexpensive medium at the time. The technique gives the illustrations a wonderful translucent quality. The museum has a collection of 1900s artworks, though only 80 are rotated through the exhibition space at a time. Don’t let the name Naïve Art dissuade you from visiting the museum as it has some great pieces on display.

Nearby was Pod Starim Krovovima, Under the Old Rooftops, the oldest tavern in Zagreb which poured its first beers in 1830. It’s a small quietly charming place that used to be the favorite haunt of Zagreb’s poets and writers, and we had hoped to eat there. However, it doesn’t serve food anymore, but it does offer a nice selection of Croation wines, beers and cordials.

Instead we had dinner at Tavern Didov San, around the corner on Mletačka ul, a quaint street that would look more at home in a country village than the city. The restaurant specializes in authentic, regional Croatian cuisine; besides the traditional hearty beef dishes there are recipes that feature frog legs, eels and snails. The restaurant’s very nice staff, its ambience, and the delicious food all contributed to a memorable evening in Zagreb.

Opening the window of our hotel room the next morning revealed the street was blocked, and preparations were busily underway for a street fair. The seductive aroma of fresh baked chocolate croissants wafted up from the pâtisserie a few doors down, and called to us to come and indulge.

It would be hours before the festival was in full swing, so we headed to Ban Jelačić Square. The equestrian statue of Josip Jelačić Bužinski (1801-1859), a Croatian military hero and politician who abolished serfdom in Croatia, is backed by some beautiful examples of Austro-Hungarian buildings built after the earthquake of 1880. The attractive square earned the city the nickname as “the gateway to the Balkans.” On the far end of the plaza was Manduševac fountain. It’s all that remains of a natural spring that is mentioned in 1700s court records as “the main night gathering place of witches and warlocks in Zagreb.” The punishment for a conviction of witchcraft was to being burned at the stake at the infamous execution spot called Zvedišće, near the entrance to Tunel Grič on Mesnička ul, too eerily close to our hotel. Witchcraft trials ended in 1756 when empress Maria Theresa condemned the practice.

Stairs lined with flower stalls led from the plaza to Tržnica Dolac, Zagreb’s daily market. It’s a large square ringed by shops selling meats, poultry and fish, while the center is covered with seasonal vegetable vendors set up under a vast sea of red umbrellas. On opposite sides of the square the belltowers of the 18th century Church of the Visitation of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Cathedral of Zagreb rose above the market’s low buildings.

Several blocks of Ilica street were vibrant with activity. In places folks had pulled couches and chairs from their apartments into the street, in order to comfortably relax while listening to buskers entertaining the crowd. Artisanal craft vendors set up tables selling handmade pottery, soaps, jewelry, toys and homemade food. We purchased a pop-up puppet on a stick whose maker assured us it would withstand the abuse of any six year old. Another vendor offered slices of her baba’s scrumptious Bregovska Pita, an 8-layer filo dough layered pie, filled with apples, raisins, and walnuts.

It was a gorgeously warm sunny April day as we sat outside at the Wave Bar. Across the way we watched folks wander through the Sunday antiques market that was underway in Britanski Square, searching for that undiscovered gem that lay hidden in the market’s cornucopia of brass, wood and glass bric-a-brac.

It was a great afternoon experiencing the energy of Zagreb, and the perfect way to end our stay in this charming city. Two full days in Zagreb were only enough to scratch the surface of this intriguing city, and in hindsight we should have planned a third day, but hopefully we’ll get a chance to return. Tomorrow, we will cross the border into Bosnia & Herzegovina.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna