The day was crisp, the sky a clear blue, the mountains beautiful with their peaks still covered with late spring snow. We zigged and zagged our way along the infamous SH21, higher into the mountains, around many challenging blind corners and switchbacks. In spots the road narrowed to a single lane, but there were pullover areas to allow for oncoming cars to pass. Fortunately, in late April we had the roads and the overlooks in this pristine region mostly to ourselves. The views were breathtaking. A half-hearted complaint if any, there just were not enough places to stop safely to enjoy the picturesque landscapes.

After cresting the Thore Mountain Pass, at 5,547ft the highest along the route, we stopped at the Monument commemorating Edith Durham, a British anthropologist who championed Albanian independence in the early 1900’s, and was lovingly called, “Queen of the Highlanders.” After that we could have coasted all the way into Theth, like Olympic bobsledders, but we were very judicious with braking.

Centuries ago, the inhospitable, saw-toothed mountains of northern Albania were a sanctuary for folks fleeing invaders. It’s a massive area at the southern end of the Dinaric Mountain Range, with nearly twenty mountain peaks having 9000 ft high summits, and it encompasses the border region where Albania, Montenegro, and Kosovo meet. The Dinaric Mountains are the spine of the Balkans, stretching from Slovenia through Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Montenegro, and Kosovo before ending in Albania, where today they are called the Albanian Alps. A much friendlier name to encourage tourism than the Accursed Mountains, or “Bjeshkët e Namuna” as the original Albanian name goes.

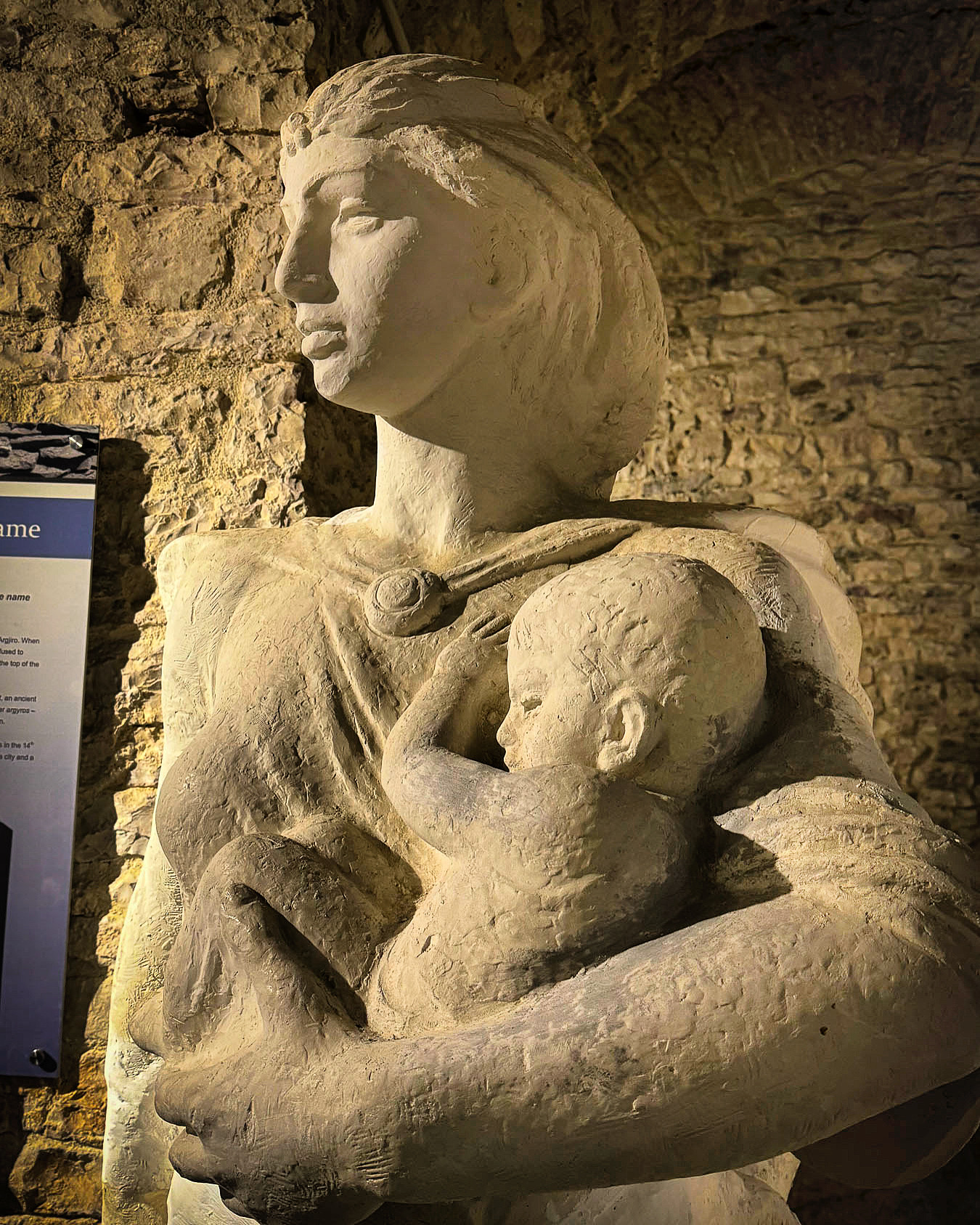

There are three prevalent legends as to how the mountains got that original title, but hardship is at the core of each. One of the earliest legends credited the creation of the torturously steep mountains to the Devil when he escaped from Hell for a day. While there are streams and waterfalls throughout the mountains, they are not easily accessible and are often dry during the summer months. These dry conditions explained the tale of a mother fleeing her burning village. Her husband was killed in the fighting with Ottoman invaders, and she took her children into the mountains to save them from being forcibly converted to Islam. The days were hot, the terrain steep and unforgiving; her children were thirsty after three days without any water. Distraught, she cursed the mountains for causing their suffering. It’s also believed that soldiers struggling to cross the treacherous mountain terrain cursed the steep slopes, and most likely used many foul adjectives to make their point.

Footpaths and donkey trails were the only way into Theth for a millennium. The village didn’t have a school until 1917. The American Red Cross arrived in Theth in 1921 to help expand the educational opportunities in the Shala Valley. The American journalist Rose Wilder Lane tells of this school building mission in her 1922 book Peaks of Shala. Communication with the modern world didn’t expand until the first dirt track, a single lane, serpentine road that crested numerous mountain passes, was carved into the side of the masiffs that isolated the remote valley in 1936. It took another thirty years before the village received electricity in 1966.

It is difficult to find accurate figures on the ancient population of Theth, which in some instances includes the entire Shala valley and its nine hamlets, and at other times just the village of Theth itself. But it’s thought that at the end of Albania’s Communist regime in 1991 the remote area had a population of roughly 3000 folks in 700 households, though it is much less today. Interestingly, most of these villagers claim Zog Diti as a common ancestor of the Shala tribe or clan. Oral tradition relates that the name Shala is derived from shalë, a saddle, a gift he was given by his brothers, when led his family into the northernmost reaches of the Shala Valley. They fled from the region of Pashtrik, during the Ottoman invasion of Albania in the early decades of the 15th century to preserve their Catholic faith.

A road changes everything. While it brought progress in its early years, it eventually was the route of exodus for families seeking non-agrarian jobs for themselves and better educational opportunities for their children. It was extremely difficult to recruit teachers to live in the “wilderness.” Currently Theth has about 370 summer residents that return to support the tourist season, but only a hearty, resourceful handful of residents winter over in the often snowbound valley.

Today the village, with its modest tourist infrastructure, is the jumping off spot to pursue outdoor activities in the northern Albanian park system that includes Nikaj-Mertur Regional Nature Park, Valbona Valley National Park, and Theth National Park. This vast area encompasses many diverse ecosystems that include oak and beech forests at lower elevations that transition to pine trees and scree-covered slopes the higher up the mountains you go. The region is home to over 50 bird species, including kestrels and eagles. And if you are lucky enough you can spot gray wolves, wild goats, brown bears, and roe deer.

We arrived at the Royal Land Hotel & Restaurant as the shadows were lengthening and the sun skimmed the snowy ridge across the valley from the hotel. Just a week earlier the hotel had reopened for the season, and we, along with several other couples, were some of the hotel’s first guests of the year. After checking in, we sat at picnic tables on the terrace outside, sipping glasses of their homemade red wine, and watching the inn keeper’s son rototill the fertile dark soil of a garden plot. The sky stayed light for several more hours, but the sun had disappeared behind the mountains behind us. The lodge is very rustic with fourteen cedar-planked rooms, and a glass enclosed dining area, where each table has fantastic views of the surrounding mountains. The Inn’s restaurant is open to the public, as are most of the hotel restaurants in the valley. The family that owns the hotel was very friendly and helpful. Their breakfast buffet and home cooked dinners were delicious, with many of the items on the menu homemade or locally sourced. The sky was clear that evening and the stars brilliant across the night sky. Early the next morning, moonlight filled our room.

Hiking is the main activity in the Shala Valley, and we eagerly headed down into the village to explore the valley. Many folks choose to trek the popular Theth to Valbona trail, a nine-hour hike one way, covering 11 miles that takes you through a pristine high alpine wilderness. Being the city folks we are, we stayed in the relatively flat flood plain of the Lumi i Shalës which tumults from its source in the mountains north of the village. Near the bridge that crossed the river we spotted an understated monument that upon closer inspection commemorated the schools built by the American Red Cross in the Shala Valley.

Farther along we reached Kisha e Thethit, Theth’s iconic church, and could hear music softly emanating from the Sunday service being held inside. Built in 1892, the church is a strong stone building with a steeply pitched roof, and a belltower, that looks like a small medieval castle, ready to withstand a siege. Though, during Albania’s communist era, the building was used as a health center. Nearby a sign pointed the way to the trailhead for the Theth – Valbonë hike. Sheep contentedly grazed as their shepherd checked his cell phone. Untethered horses sauntered nearby.

From the church we could see Kulla e Pajtimit, the Reconciliation Tower, or “Lock-in Tower,” and headed there. The formidable two-story stronghold, with three small windows, was built four centuries ago, and served a dual purpose; to provide shelter for the villagers in times of trouble, and to serve as the reconciliation tower, a neutral ground where disputes within the village were resolved by a council of elders. In more serious cases that involved a murder or threat of murder for revenge, the accused party would be locked in the tower for fifteen days as a cooling off period, while the elders tried to reconcile all parties affected by the crime.

This millennia old tribal custom was widespread throughout Albania and was part of the “Code of the Mountains,” that was passed down through an oral history tradition from generation to generation until it was codified in the 15th century by Lekë Dukagjini, an Albanian nobleman and contemporary of Skanderbeg, an Albanian hero. Since then, the tribal laws have been known as the Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini. The kanun has an extensive set of 1263 rules that cover everything from beekeeping to marriage and honor. It is most famously known for obligating families to partake in gjakmarrja, (blood feuds), that permitted koka për kokë (a head for a head), and hakmarrja, (vendettas), to maintain honor by seeking revenge. The heavy hand of Albania’s communist government had some success in outlawing this practice, but unfortunately, it’s still an issue for law enforcement today.

Later we stopped for lunch at the Thethi Paradise restaurant and enjoyed fresh trout, grilled lamb, and a few Korça beers, at an umbrella covered table on the patio.Surrounded by mountains from end to end, the Theth Valley was absolutely stunning and serenely tranquil in its “majestic isolation,” borrowing a phrase from Edith Durham.

The next morning, we retraced our drive across the mountains to Shkodër before continuing south to the Lezhë Castle and Kruje, where we spent the night. The drive out of the valley was just as beautiful as the drive in.

Our only companions on this quiet stretch were a flock of sheep being herded down the road, and a sow followed by her piglets crossing behind her. The drive was uneventful until the bridge over the river ahead of us was closed for road repairs, and we were directed to follow a deeply rutted farm track through the countryside for several miles. The road surface was so unforgiving that the car bottomed out several times regardless of how slowly we were going. At this point we didn’t have a cell signal, and there were no other detour signs, so we had to dead reckon our way back to the highway. The rental car company had cautioned us that they prohibited driving on dirt roads, and that we would be fined if their satellite tracking recorded us doing so. We kept our fingers crossed.

It was easy to spot Lezhë Castle, perched high on a hill, from miles away. Though getting there was a little more challenging and involved driving on some of the steepest roads we ever encountered. Think hills of San Francisco steep, but worse.

The castle had a commanding view of the surrounding terrain, though especially important was its western vista, where ships on the Adriatic Sea could be spied before they reached Albania’s shore. It was in this castle in 1444 that Skanderbeg, Albania’s national hero, rallied his countrymen to resist the occupation of the country by the Ottoman Empire. The best view of the castle was from the parking area. The area behind the walls is left in a rather rustic state with tumbled ruins and cisterns to explore. Overlooking the sea, we enjoyed a picnic lunch in the shade of the ramparts.

The hillside town of Kruje, set high above the Tirana Valley, was our last destination in Albania. On our way to the Hotel Panorama we passed a large statue of Skanderbeg astride his steed, which commanded an overlook in a city park.

Albania’s national identify, a spirit of perseverance and resistance, is intimately linked to Skanderbeg and Kruje, his hometown. Born into the noble Kastrioti family during the early 1400’s, his parents were forced to give him to the Ottoman Empire as part of Sultan’s devşirme system. This “child tax” was to ensure a family’s loyalty to the sultan. Only one son could be taken. These children were then taught the Koran, given an education, and raised as Muslims, before being sent to serve in the Ottoman Empire’s Janissary corps, a highly trained infantry. Skanderbeg excelled as a skilled Ottoman soldier and rose through the ranks. But after a 1443 battle in Serbia he renounced Islam and escaped back to his homeland and reclaimed his title. A year later he led a league of Albanian Princes in revolt against the Ottoman occupiers. For over twenty years he rallied his fellow Albanians to repel 13 invasions, and was considered a hero throughout a Europe that feared the expansion of Islam across the continent. The citadel in Kruje was his headquarters during this time and endured three intensive sieges. Ten years after Skanderbeg’s death the castle fell and the Albanians relinquished their independence to the Ottomans for 400 years.

Its name said it all, and the Hotel Panorama’s guest rooms and rooftop terrace were the perfect spot for views out over the town’s ancient caravan market and Kruje castle. An arched stairway descended under the hotel from the main street and led to the historic bazaar, which is over 400 years old. A 16th century minaret towered above us.

It’s believed to be the most historically accurate representation of an ancient marketplace in Albania, with its cobbled street centered with a drainage divert and canvas awnings hung from the shops, to protect shoppers from the midday sun.

In centuries past it would have had a full array of merchants offering a wide assortment of ancient everyday items, and luxuries crafted in faraway lands. Today, it’s a gauntlet of tourist themed merchandise, but we found one hidden gem, the Berhami Silver shop. The proprietor and sole craftsman, specializes in unique, intricately woven filigree jewelry.

We shielded our eyes from the bright sun as we left the long, arched tunnel through the ramparts, and looked up at the Skanderbeg National Museum. Built in a historical style to reflect its surroundings, it was a majestic sight, its sandstone blocks glowing in the afternoon sun, and the red and black Albanian flag full out in the breeze.

Its exhibits feature artifacts from Skanderbeg’s era and Albania history. One of the most intriguing displays was a replica of the hero’s signature goat head-topped helmet. Albania’s flag evolved from the two headed eagle on the Byzantine Empire’s flag which flew over Albania from the 4th to 14th centuries.

The double eagle heads symbolized the unity between the Orthodox Church and the Byzantine Empire. The black eagles above the Kastrioti family coat of arms on a crimson background became the flag of rebellion when Skanderbeg raised it above Kruje in 1443. Its colors black and red represent the strength, bravery and heroism of the Albanian people.

Above the castle we rested outside at a small café with an expansive panoramic view. Unaware of castle’s closing time we headed down the slope to the Tekke of Dollma, a small Bektashi Sufi shrine that contains the tomb of the mystic leader, Baba Shemimi. We reached the gate of the tekke’s courtyard just as the caretaker was about to lock the door for the day.

Graciously, he let us stay for a few minutes. The building was still under repair from the 2019 earthquake, but still very interesting. Legend believes the ancient olive tree in the courtyard was planted by Skanderbeg. The castle was a wonderful site to explore, and if we had had more time, we would have visited its ethnographic museum.

The sun was casting a golden glow across the hillside by the time we reached the rooftop terrace of our hotel. We clinked glasses and reflected back upon a fabulous vacation exploring Albania.

Till next time, Craig & Donna