Šiauliai, the Hill of Crosses, and the rustic wooden Chapel of Jakiškiai were our only stops in Lithuania. All three were incredibly interesting, and an art filled Šiauliai was a fantastic discovery that we hadn’t expected but thoroughly enjoyed wandering through. The city of Vilnius, Latvia’s capital, required a time-consuming loop to the east that we chose to forgo, but hope to have a chance of visiting in the future.

It was a beautiful fall day as we recrossed the border into Latvia. Our route took us through the Zemgale Plain, Latvia’s agricultural heartland, an area flat to the horizon as far as our eyes could see. The country’s most fertile region, it’s often called the breadbasket of Latvia. Farmers ploughing their fields revealed dark rich soil ready for the planting of winter wheat.

We don’t do a lot of research before a trip, just enough to determine that we will probably enjoy where we are headed. We find spots along our intended route, to break up the drive, by examining Google maps the evening before the next morning’s departure. That’s how we discovered the Rundāle Palace, an exquisitely restored 18th-century baroque manor with ornamental gardens and museum highlighting the history of the Dukes of Courland, and their thoroughbred stud farms that were renown throughout the Baltics and Russia for the horses they supplied for the equestrian pursuits of various royal courts.

The interior of the palace was splendidly restored with period furniture and elaborate stucco decorations in every room. It was one of the nicest estate type homes we have visited in Europe, and was well worth the price of admission, something we can’t say for some of the other “palaces” we’ve toured.

Being gardeners, we enjoyed the extensive formal landscape plantings that have been described as the “Versailles of Latvia.”

Ten minutes down the road, Bauska Castle stood strategically on a small hill above the confluence of the Mūša and Mēmele rivers where they merge to form Lielupe River, a vital trade route in ancient times through southern Latvia. It was the highest point of land we had encountered in several days. Originally it was a hill fortress built with timber by the Semigallians, a pagan tribe noted for their strong resistance to the Livonian Order of Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, before their subjugation in the last years of the of the 13th-century. In the early 1400s the knights constructed the first stone castle on the hill. It became one of the main residences of the Dukes of Courland, before the Rundāle Palace was built, when the castle was given to the Dukes after the Livonian Order collapsed in 1562.

A long path through dense woods led to a vast field dominated by five towering brutalist, as in the Soviet style, depictions of prisoners. The field was once Salaspils Camp (1941-1944) built by the Nazis as a “detention center,” for political prisoners and a “labor correction camp,” for Latvians who resisted the forced labor demanded of them by the occupying German army during World War 2. It was later used as a “transit and collection camp” for Jews before they were sent to concentration camps in Poland and Germany. One thousand Jews were brought from Austria, Czechoslovakia, and Germany, to build the camp, and died from exposure during the brutally cold winter of 1941/1942. Two walls of barbed wire and six towers with machine guns, search lights and sirens that wailed at any sign of escape surrounded the field.

It’s estimated that over the camp’s three years of operation, 23,000 people, half of them ordinary citizens captured during special campaigns against civilians in Belarus, Russia and Latgale, a region of eastern Latvia, were imprisoned behind its barbed wire. Trainloads were sent as forced laborers to Germany, and roughly two-thousand men were forcibly conscripted to fight for the German army.

In the museum a video displays historical footage of the camp when it was liberated by the Russian Red Army, including survivor testimonies as documentation of the brutality the Nazis inflicted upon the people of Latvia. Many in Latvia believe the Soviet Union built the Salaspils Camp Memorial in 1967 during the communist occupation of Latvia as propaganda to divert attention away from their policies of deporting Latvians to Siberia and Ukraine, while depicting themselves as great liberators who also suffered at the hands of the Nazis. The communist regime ignored the fact that the Soviet Union’s 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, a non-aggression treaty with Nazi Germany, contained a secret amendment that allowed the USSR to forcibly annex Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, while Germany invaded Poland, starting World War 2. The irony of our visit to this somber site on a sunny fall day was not lost on us. We can only hope for a better future.

The flat farmlands slowly changed to rolling hills then mountains as we drove into the Gauja National Park, Latvia’s largest nature preserve, which surrounds the small town of Sigulda, and straddles both sides of the picturesque Gauja River valley, as it flows through the Vidzeme region. An area filled with steep ravines and historic medieval castles, which is often referred to as the “Switzerland of Latvia.” It’s an outdoor enthusiast’s paradise with over 560km (350 miles) of hiking trails and 320km (200 miles) of cycling paths, all of which are popular with the cross-country skiers during the winter months.

There might be a little bit of wishful thinking along the lines of “one country’s mountains are another country’s hills,” as the highest point in the Gauja National Park is 160 meters (525ft) tall. Though that’s the equivalent of 52 story building and a significant height if you had to climb the stairs to the top, especially if you are from the lowlands around Riga. During the winter months the region is a snowy wonderland with several ski resorts and a bobsleigh, luge & skeleton track that twists down a Sigulda mountainside for 1.2 km and has 16 curves. It’s a challenging course successfully used by the Latvian National Team to train ten Winter Olympics medalists since Latvia’s independence in 1999. One team won a gold medal in the four-man bobsled event at the 2014 Sochi Olympics, in Russia.

The Emperor’s Chair was not far from the sports complex and offered a nice view of the Gauja River flowing through its valley, which was just beginning to show the first signs of autumn color in late September. Sigulda is a quaint town without a center as the buildings along its treelined streets are very far apart. Now late in the afternoon, we checked into the Hotel Sigulda, a beautiful older ivy-covered building. The front houses the restaurant, with rooms above which hide a modern wing that faces the parking area. The hotel would be our home for the next two nights while we explored the surrounding area.

The next morning was very overcast as we entered the grounds of Sigulda’s New Castle and Old Castle. Partially restored stone ruins are all that remain of an older fortress that was built in the 13th century by Order of the Sword Brothers over the spot where an 11th century log fortress built by the Livonians of Gauja advantageously overlooked the river and Turaida Castle across the valley to the north.

By the late 1700s the von der Borch family had acquired the ruined castle and its surrounding lands. A century later a von der Borch daughter, Olga, married Prince Dmitry Kropotkin of Russia and the estate was passed to him as part of her dowry.

Construction of the Sigulda New Palace, a neo-gothic style manor house, began in 1878 with masons reusing stones taken from the older ruins; the best local woodworkers were hired to craft the fine interior. Princess Kropotkin was instrumental in getting the new railway line from Riga to Pskov, which then branched to St Petersburg and Moscow, to run through the town, and promoted Sigulda area as a burgeoning resort area. Her son Prince Nikolai Kropotkin followed her civic mindedness and built the first bobsleigh and luge track in Latvia and the Baltics.

The interior of the manor style castle is full of highly polished wood and stained-glass windows. But we thought the best part was being able to climb the circular stairs of the building’s tower to the catwalk at the top.

Even on a rainy day it offered a spectacular panoramic view of the old castle and the refurbished outbuildings of the estate that now host workshops and craftspeople selling their wares.

It was from this lookout that we spotted the aerial tram that crosses the river valley from Sigulda to the Turaida Museum Reserve.

We drove there instead as we thought it was too windy for us to take the aerial lift, after a pleasant lunch at Kaķu Māja, the Cat House, which also operates as a bed & breakfast inn. It is a very pretty restaurant that has a nice vibe. The food is served cafeteria style and was surprisingly very delicious, while also being extremely budget friendly.

The Turaida reserve is a large 42 hectares (104 acres) park with a partially restored medieval castle, period buildings and Dainu Kalns, which translates as “I sing the mountain,” but is commonly referred to as Folk Song Park, a tremendous rolling field with over 25 large stone sculptures inspired from Latvian folktales by the artist Indulis Ranka.

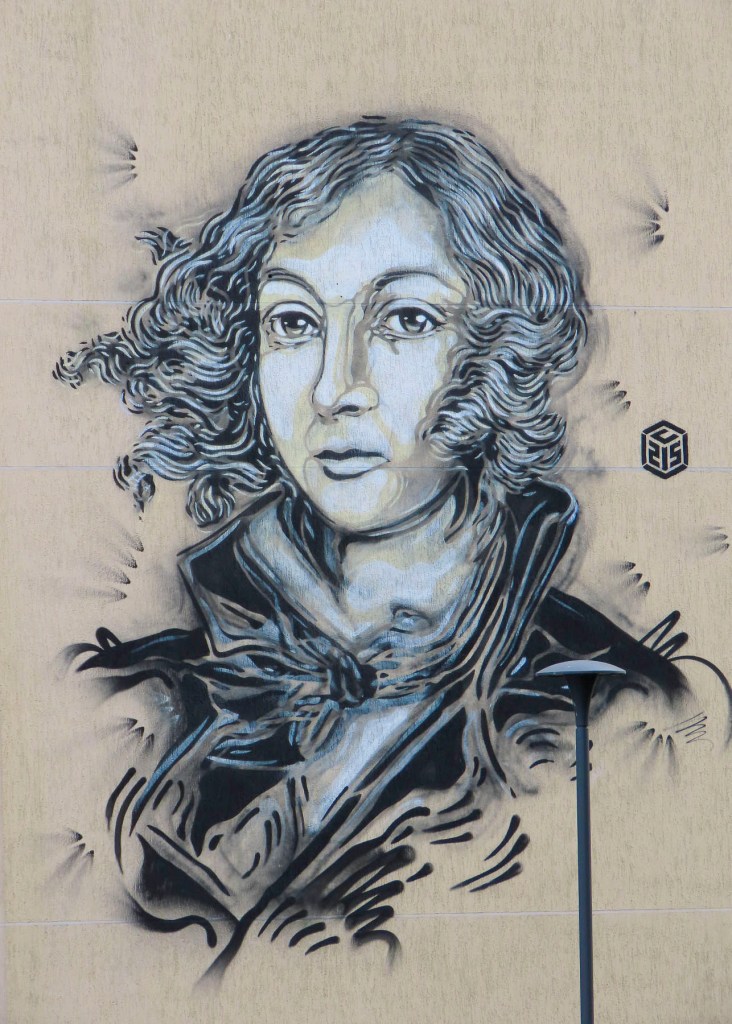

Dainu Kalns was constructed in 1985 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Krišjānis Barons, a Latvian folklorist who collected and transcribed over 30,000 of the country’s folk songs that had been passed down through the generations, and is recognized as being an important contributor to Latvia’s National Awakening in the mid-19th century. Folk Song Park also hosts various folk festivals throughout the summer months.

You have to admire the gumption of the city of Cēsis, a forty minute drive through a beautiful landscape from Sigulda, for declaring themselves the Latvian Capital of Culture 2025, the first in the country, after losing the title of European Capital of Culture 2027 to the Baltic port city of Liepāja . This was on top of an earlier disappointment in 2014, when Riga won the honor. Not wanting to see all their efforts of planning fall by the wayside, city officials designed a year-long celebration with numerous historical and art exhibitions, dance performances, theatre, and concerts with the motto – “Culture in minds, castles, and yards.”

Cēsis is considerably larger than Sigulda and has a well-established old town with Rīgas iela, a pedestrian mall running for several blocks through its core. We arrived to the Cēsis Castle late in the afternoon, as the sun was painting the rough castle walls in its golden glow. It shares a similar history with the castles of Sigulda. Construction of this castle started in 1209 and in 1279 Teutonic knights rode from the castle into battle carrying a red-white-red banner, first noted in the 13th-century Livonian Rhymed Chronicle.

Legend believes this banner was made from the bed of a knight fatally wounded in an earlier battle. The colors became the Latvian flag. By the mid-1400s the castle was the permanent base of the Livonian Order of Teutonic Knights, and the growing town’s location near the Gauja River made it a key trading hub, which led to its membership in the Hanseatic League in the early 1500s.

Crossing a creaky drawbridge over a dry moat, we entered the courtyard of the castle and were greeted by a Latvian maiden, a costumed reenactor, who offered us two glass lanterns holding lighted candles to illuminate our way through the dark passages of the fortress. I was about to decline, but Donna convinced me otherwise with “come on, this will be fun,” and it was! We carried them up and down the narrow tower stairs and through various cavernous halls with only the ambient light from small windows providing a little bit of illumination.

The third floor of the tower hall hosted the immersive Multimedia Story of Cēsis Castle, that used surround sound and digital technologies to project an engaging animated film onto the castle’s walls.It was very well produced and contributed greatly to our understanding of the history of the area and life in a medieval castle. It was really surprising how such a simple prop as a lantern could enhance our experience so much. We had a great time, and it was well worth the modest admission price.

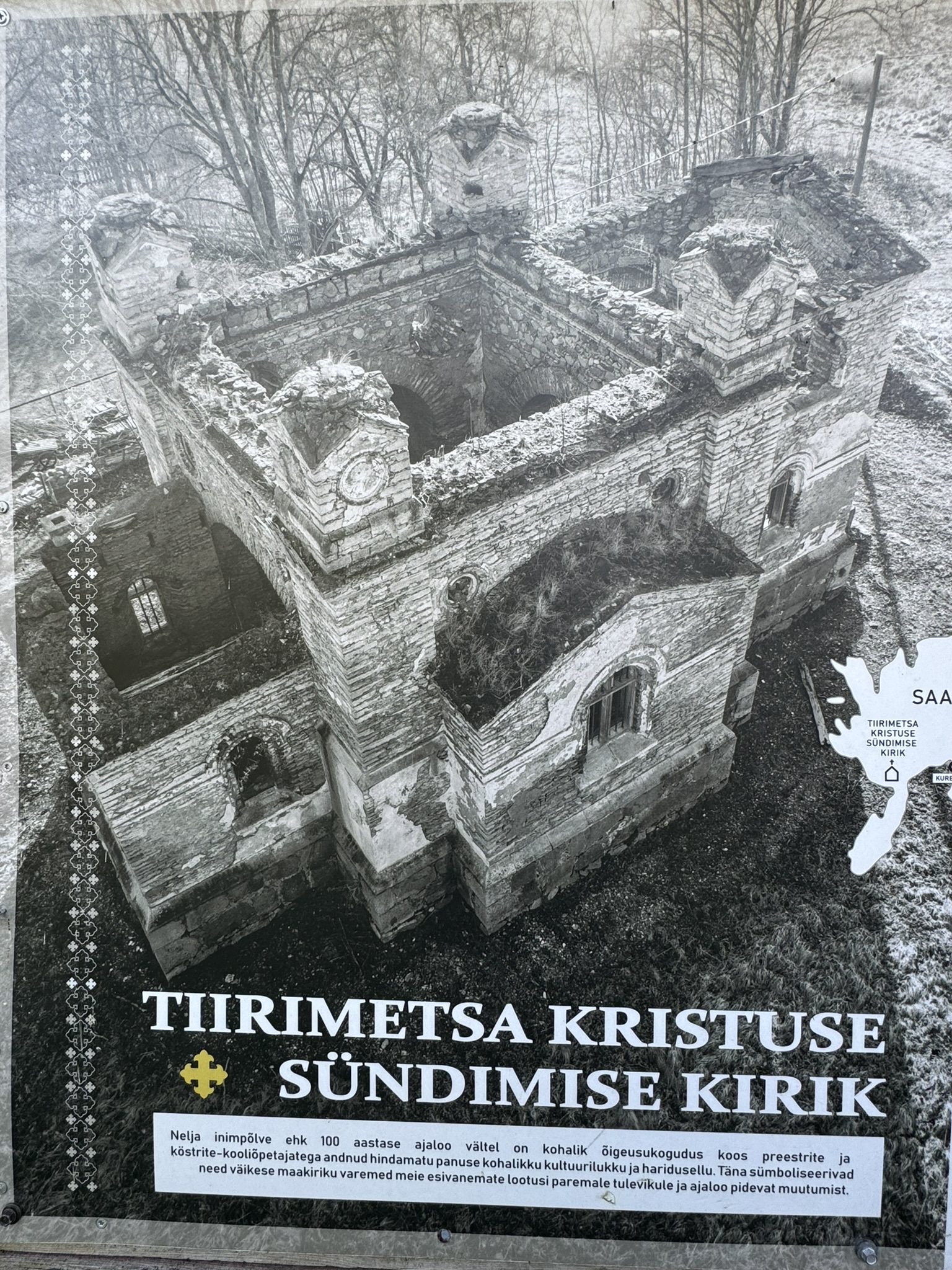

On the way out of town we stopped in the park below the castle to photograph Cēsis’ pretty Byzantine style Enlightenment of Christ Orthodox Church, which dates from the mid-1800s.

On our way into Cēsis earlier an old cemetery caught our attention. We had time to stop and wander through it now as we drove out of the city. The cemetery was interesting but very neglected with overgrown bushes and roots covering toppled headstones. It’s named Vācu kapi, though it’s also referred to as the German Cemetery, as it contains 371 graves bearing the Iron Cross, identifying German soldiers killed in Latvia during WW2.

But there are also the graves of Ottoman Empire soldiers who died in Cesis as prisoners of war during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878. The Turks weren’t really incarcerated – “First they lived in Cēsis under supervision, but afterwards, as they were so far away from their motherland, their regime became freer – they could traverse the city, go to the pub, the sauna. After a while some went back to their homes, while others struck root in Cēsis.” But it’s also believed the cemetery contains the graves of Latvian Germans, Russian atheist, and some Jewish citizens of Cēsis. Most of the vandalism to the cemetery is thought to have occurred during the communist occupation of Latvia. It’s an interesting side note to the history of a complex part of the world.

In hindsight, staying in the larger town of Cēsis might have been a better choice, as it has a compact historic center with cobbled streets and shops that would have been interesting to explore had we stayed there.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna