Why Estonia? We are sure folks can relate, our pockets aren’t as deep as we’d like, but that doesn’t keep us home. A low budget, off-season destination is more attuned to our lifestyle anyway. So, when an under $400, September fare from New York City to Tallinn, Estonia popped up in our email we jumped at it after some research confirmed we could find some very nice hotels from $50 to $100 per night, often with breakfast included. Exploring the lesser visited Baltic countries of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania also fulfilled our desire to extend our travels beyond western Europe, which previously had been very Mediterranean-centric. Living in the very hot and humid southern United States is also affecting our decisions concerning vacation destinations, as we are now seeking alternative destinations as a result of climate change. The heat of a southern summer often continues into September and October, with temperatures at home in Georgia often in the high nineties. Estonia offered a wonderful reprieve from the sweltering summer heat with a daily high average of 14°C (57°F).

The history museum at Maarjamäe Castle was an unusual first stop for us after picking up our rental car at the airport. But it was the closest we’d be to it during our three-week road trip through Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The museum is in a renovated 17th-century chateau, which was left to ruin for decades during the communist Russia occupation of Estonia. It is beautifully set on a bluff across from Tallinn Bay, and was built by the Brotherhood of Black Heads, a professional association of unmarried ship owners, merchants and foreigners dating from the 14th century, as a summer retreat.

Today the museum’s permanent exhibit, My Free Country, explores 100 years of modern Estonia’s history, from its 1918 declaration of independence from Russia, and the following War of Liberation, through twenty years as a sovereign nation before being invaded by Nazi Germany and communist Russia during the Second World War. The fifty years of brutal Russian occupation after World War II and communist propaganda are also covered, up to Estonia’s 1991 second declaration of independence from Russia, which was overwhelmingly supported by 78 percent of Estonians. It’s a difficult mission to reconcile the terror of the communist years into a bright, hopeful future, but historical research, as well as oral histories, document forced resettlements to Siberia and imprisonment in labor camps during the Soviet reign of terror, when Estonians were prisoners within their own country and shot if they tried to escape. The exhibit highlights a proud history of an unrelenting desire for freedom, which prevailed under the worst conditions. A history that, it is hoped, the younger generation of Estonians, who have not experienced communism, never forgets. As one quote on an exhibit referring to Russia said, “Nothing good ever comes from the east.”

After the 1991 independence, colossal, large-scale Russian propaganda sculptures, which once dominated prominent public spaces across the country, were removed from view but not destroyed, as they are part of Estonia’s history. However, they were erected behind the museum in a space fittingly called, with Estonian humor, “the Soviet Statue Graveyard.”

Our first lunch in Estonia was at the museum’s café, Maarjamäe Resto, an unexpected culinary delight, which could be considered a destination in and of itself.

It was still too early to check in to our hotel in Tallinn, so we headed nearby to the Tallinn Botanic Garden, a large park with an extensive greehouse. The grounds were quite pleasing with their plantings, and the greenhouse with its various collections of tropical plants was very interesting. Though in the section filled with cactuses from around the world, Donna, ouch!, accidently brushed one with her hand and imbedded some spines into her skin. Not a huge issue when you are home and have the proper tools to pluck the pesty spines from your skin and relieve the discomfort, but when you are traveling, it’s another issue entirely.

Fortunately, the barista operating the café in the greenhouse had dealt with this before, and he ran out to his car to fetch a roll of good old-fashioned duct tape to grasp those microscopic thorns. He was very nice, a 30ish Italian man who during conversation jokingly related that being a part time medic was not part of his job description when he was hired, and visitors getting pricked with cactus thorns happens more often than you would think. We were curious how a warm-blooded southerner ended up in the northern Baltics. “You know there is always a woman to blame, and I followed my love back to her Estonian homeland.” We asked if he missed the warm Mediterranean weather and la dolce vita. Yes, the weather is nicer, so we visit my family, but life is better here in Estonia as there are more opportunities for those willing to work and get ahead. Estonia is leaps and bounds ahead of the other European countries in embracing digital technologies. So much so that the government considers internet access a fundamental right and ensures that everyone across the country, even on the smallest islands, has reliable internet, and offers digital literacy programs for the technology challenged. The government also endorses working from home remotely, and offers an Estonian Digital Nomad Visa. “Estonia is very big in cybersecurity, and this enables every person, business, and government institution to be connected. We are one of the most digitally advanced countries, and we can even vote securely online in Estonia.” This digital future contrasted with as well as complemented the vibrant centuries-old walled city of Tallinn.

Despite not having particular plans for Tallinn, we knew we would enjoy exploring the city as soon as we saw the ancient architecture along the way to our hotel. Having a rental car and finding a hotel with free parking is difficult in any city, but we scored big withTaanilinna Hotell. The hotel was in an excellent location, just on the opposite side of the old town’s historic ramparts, and a short walk from the 14th-century stone towers of the Viru Gate’s flower market.

Google Maps got us close, but the hotel was a little difficult to find, and we mistakenly drove through a pedestrian only area; fortunately, there were few people about. In order to find the hotel, we parked and walked down the street, when we spotted the hotel’s sign, which was set back from the lane. It’s a modest hotel, and the staff was very nice. We enjoyed a quiet 4-night stay.

With Tallinn’s old defensive wall only a stone’s throw away, history surrounded around us, and we quickly set out to explore and to find a place for dinner as twilight descended on the old town. Our wandering took us down various lanes, past distinctive centuries-old 4 to 5 story tall buildings that served, as was the medieval custom of the time, as the multifunctional home/warehouse/offices of wealthy merchants.

Lights twinkled on and illuminated the cobblestones in a golden glow. I know it’s cliché, but our first impressions of Raekoja Plats, the Town Hall Square, anchored with its soaring 64M (300FT) tall 13th-century watch tower, were beautiful, charming and magical. We were disappointed to learn that the tower is only open from the beginning of June to the end of August. We love a good tower climb!

Still retaining its original footprint, Tallinn is one of Europe’s best preserved medieval cities, with 26 watchtowers along its ancient ramparts and city gates, topped with distinctive cone-shaped red roofs. The walled city still encircles a vibrant and active community, which supports a lively arts scene, along with a robust nightlife.

Its preservation seems surprising for a city that has stood at the crossroads of conflict since it was founded by a Danish King in the early 1200s. In addition to the Danes, Tallinn has been ruled by the Brotherhood of the Sword, the Teutonic Order, the Holy Roman Empire, the Swedish Empire, Czarist Russia, Nazi Germany, and the Soviet Union. The city’s prosperity and resilience throughout the centuries is testimony to the strong spirit of the Estonian people.

One of the nice things we enjoy about staying in one place for several days is the opportunity to experience the locale as it quietly awakens with the sun. Whether it is cloudless blue skies or a place cloaked under clouds with folks huddled under umbrellas to ward off the rain, a place breathes and its mood changes by the hour, from day to day. The destinations on our walks were always different, but we often crossed the same lanes and stopped to photograph something different that caught our eye, which we hadn’t noticed before.

Old town Tallinn is mostly flat and is a wonderfully walkable city. There is a short uphill stretch to Toompea Hill (the upper city), where we visited the Kiek in de Kök Museum, the Bastion Tunnels, and Neitsitorn, the Maiden’s Tower. During the 1700s when the towers lost their military significance they were often repurposed as private apartments, with a craftperson’s workplace on the lower level, and rooms above. During both world wars the tunnels were used as air raid shelters. While the towers were lived in continually, most famously by the Estonian painters and twin brothers, Kristjan and Paul Raud, until the 1960s, when the city deemed them unsafe for habitation. Abandoned, the towers became a destination for homeless squatters and Estonia’s emerging counterculture. The extensive tunnels were an area the police refused to go. A popular, unlicensed bar opened in the tower on New Year’s Eve in 1980. Unfortunately, it didn’t survive the economic turmoil of the era as the Soviet Union began its descent into a failed state.

After an extensive multiyear renovation, the Kiek in de Kök Museum opened in 2005. The Maiden’s Tower now hosts a new Neitsitorn café, which has a nice view out over the Danish King’s Garden, and the ghostly blackened bronze statues of three monks named Ambrosius, Bartholomeus, and Claudius. Legend holds that they occasionally appear spectrally in the garden, though the only thing that appeared the morning we visited was a sleek red Ferrari 296 GTB that was the center of a photo shoot. The tower also has the re-created art studio of the twins, Kristjan and Paul Raud. The tunnels under the ramparts have been creatively reenvisioned and now house a variety of interactive digital multimedia and historical exhibits.

A walkway along the ramparts between the towers at the museum led to an exhibit about Tallinn’s café culture. Though the first coffee house opened in the town of Narva in 1697, Tallinn didn’t get its first café until 1702 when one opened on Town Hall Square. The oldest still-operating café dates from 1864, when the renown marzipan bakery, Maiasmokk, decided to offer coffee to go along with their tasty, sweet treats. After 160 years the Maiasmokk Café, even surviving nationalization during the Soviet occupation, is still open and a beloved cultural institution in Tallinn. Most of the exhibits address Tallinn’s café culture during the repressive communist era, when going to a café to share a coffee was one of the few recreational activities people could afford. With our “walk a little then café” philosophy for exploring a city, we felt we had found kindred spirits in Tallinn.

Decades later Estonian’s infatuation with coffee continues. This cultural obsession was fully on display when Estonian singer Tommy Cash performed “Espresso Macchiato,” during the finals for Estonia’s 2025 Eurovision contest and came in third place! Though in Italy some humorless Italians didn’t like the caffeinated cliches and called for the song’s banning.

Other points of interest on the hill included the onion-shaped spires of the Russian Orthodox Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. It’s across the street from the pink building that houses the Estonian Parliament. (A very good eye-level view of the cathedral can be seen, on the uphill walk, from the restored bell tower of the mid-1400s St. Nicholas’ Church.

He was the patron saint of merchants and seafarers. It was formerly one of the wealthiest churches in Tallinn until it was severely damaged by WWII bombing. Fortunately, many of its fine ecclesiastical art works, acquired from the art capitals of Europe during the Hanseatic era, had been removed from the church for safekeeping at the start of World War II. Now restored after a 30-year long renovation, the church serves as the Niguliste Muuseum, and exhibits the works that survived that cataclysmic war. Fortunately, the 105 meters, 345 ft, tall spire has an elevator that whisked us to the viewing deck.)

Farther along in one of Tallinn’s oldest churches, the 13th century St Mary’s Cathedral, there is a unique private worship box, totally enclosed with shaded windows, built directly across from and on the same level as the pulpit. Jokingly, we speculated it was designed for a wealthy patron so he could fall asleep and snore, without embarrassment, as the priest orated endlessly.

The hill also has the best vantage point for cityscapes of Tallinn’s historic skyline, the Patkuli Viewing Platform, and a mysterious red gorilla, that seems incongruously out of place. But we will leave him for you to find.

Stairs from the viewing platform ascended back toward the lower town, and we were close to Balti Jaama Turg, the Baltic Station Market. It was Tallinn’s first train station constructed in the 1860s, and became a market hall in 1993. A major renovation in 2017 totally revamped the three-level market, which has become a magnet for residents and tourists seeking a lively venue filled with diverse international eateries, antiques vendors, clothing shops, and food stores.

The next day, closer to our hotel, we wandered about, climbed more towers, walked along arched and tunneled alleyways, and descended into a cellar or two. Our walk along Müürivahe Street to the Hellemann Tower and Town Wall Walkway was quite interesting. The real prize was the view from the tower window towards Town Hall Square – it was a panorama filled with red tiled roofs and steeples.

Across from it was the Dominican Convent built in 1246. It was the oldest monastery in Tallinn and supported the adjacent St. Catherine’s Church which was completed in the early 1300’s. The convent couldn’t exist solely on the alms it collected, but the friars were an industrious group who supported themselves as farmers, and traders of fish, while also operating a brewery that sold four different kinds of beer, while they spread the gospel. “The monastery also drew profit from the veneration of relics,” and at one time, records suggest, they had “twelve silver reliquaries containing the heads of saints, with each head reputed to cure a different set of diseases.”

But everything came to an abrupt end during the Protestant Reformation in 1524 when a Lutheran mob ransacked the church and monastery, and the friars were expelled from Tallinn. A partial restoration was undertaken in 1954, and it’s now a museum, which also hosts art exhibits. Its rough stone chambers and some fine carved stone works were intriguing. We didn’t notice any fireplaces, which left us wondering how difficult living within these spartan walls must have been.

Next to the monastery is Katariina käik, St. Catherine’s Passage, an old medieval lane that separates the church from the surrounding buildings. Today it’s lined with restaurants offering Estonian cuisine, and artisanal crafts shops, featuring the talented women of the Katariina Gild who craft jewelry, weavings, ceramics, blown glass, and leatherwork. At the far end of the lane, under the arched entrance off Vene Street we found the Restaurant Munga Kelder to be a nice place to dine.

Within earshot of a town crier’s call was the Masters’ Courtyard. It similarly has unique craft vendors, but also has a restaurant that fills the courtyard with rustic tables covered with colorful tablecloths, which gives the courtyard a joyful, boisterous look.

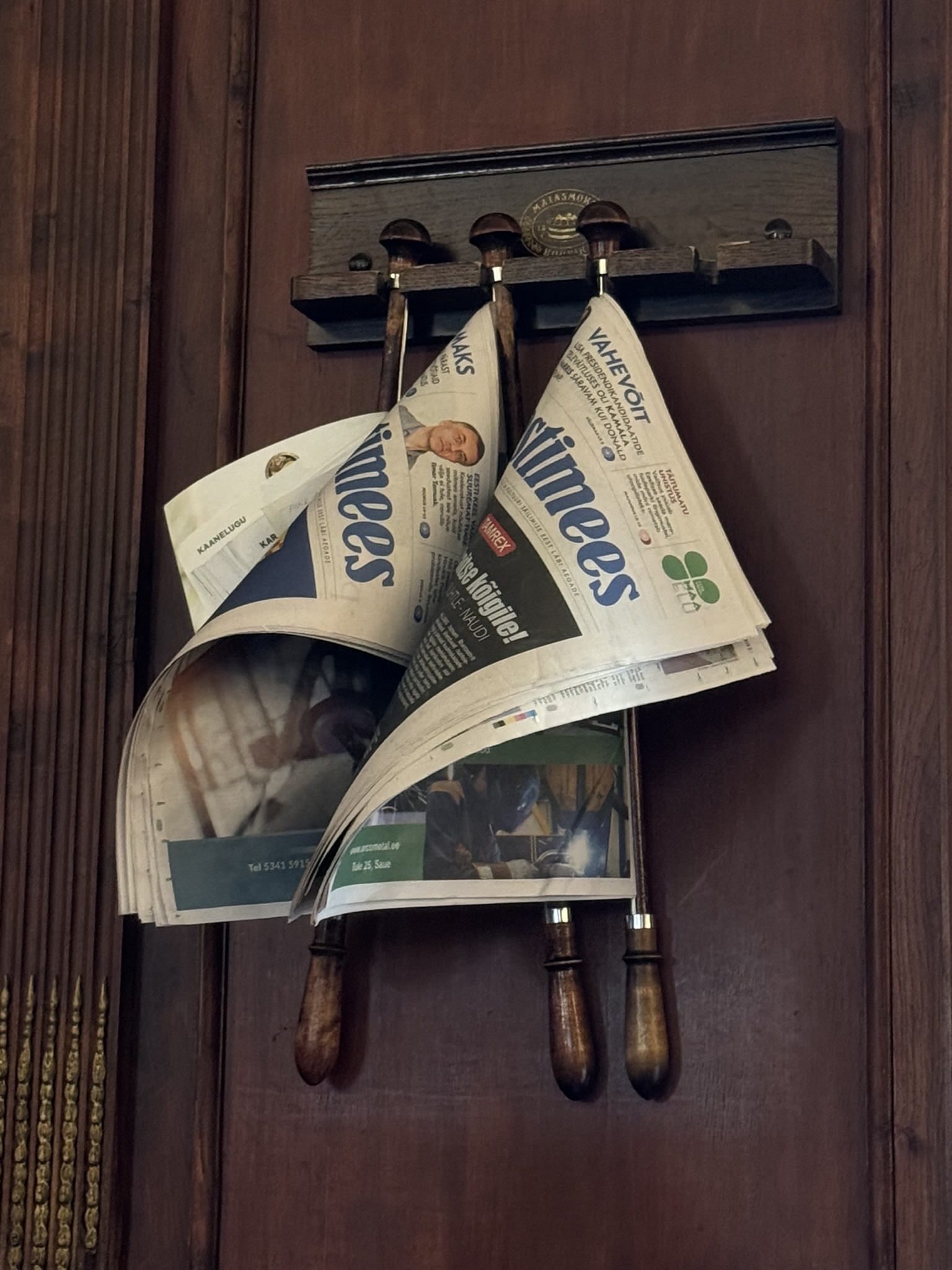

Marzipan lovers, we had to stop one afternoon at the Maiasmokk Café. The ambiance in the front room was very old school with an ornate ceiling, and mirrored walls with polished wood trim and newspaper hooks! When’s the last time you’ve actually seen a newspaper? Their colorful back room is a temple to marzipan with display cases showcasing the sweet crafted into figurines and other shapes. The variety was just mind boggling. And if your timing is right you might be able to see them being made.

With our sugar cravings satiated, we checked out Tallinn’s Great Guild Hall, directly across from the café. It featured several floors of interesting exhibits dedicated to the city’s history and trade guilds.

Across from the guild hall and the café is the Church of the Holy Spirit. During the medieval era it was the main church for everyday folk in Tallinn, and the first chapel to offer masses in Estonian, not German or Latin as was the tradition of the other churches in Tallinn at the time. With its stark white interior and original dark wood ornamentation, it is one of Tallinn’s least altered churches.

There were several other interesting facades down the street from the Great Guild Hall.

Tallinn has a rich nautical heritage that started during the early Viking era in the 6th-century when the area that would become Tallinn was a stop on the Baltic trade route that connected Sweden to Constantinople. The area of Tallinn traded furs and bog iron for wine, spices, glass, and jewelry. Shortly after the Danes established rule over northern Estonia in the early 1200s, Tallinn now a larger port city, joined the Hanseatic League, a confederation of medieval trading cities located along the Baltic and North Sea coasts. The Dutch, German and Swedish merchants of this association brought several centuries of prosperity to the city that’s still reflected in the fine examples of merchants’ houses and guildhalls that line Pikk Street. The league’s maritime trading also supported ship building which remained a vital industry through the Soviet Era which saw the shipyards build warships and submarines for the Russian navy.

The importance of Tallinn’s maritime history is well told with two museums in the city. One is housed in a squat, round, 16th-century cannon tower called Fat Margaret, which once guarded the port, but now is a modern, state of the art museum, with ship models, interactive displays, and the hull of an excavated wooden shipwreck to view.

Its sister museum is on Tallinn’s waterfront at the Lennusadam Sea Plane Harbor. It was raining heavily the day we visited, so we didn’t see the historic ships docked outside, but we did enjoy the full-size boats on display inside the old seaplane hangar. Especially the submarine Lembit, built in Tallinn and launched in 1936, which was the pride of the Estonian Navy.

The large concrete hangars themselves are noteworthy, as the three connected shells were the largest reinforced concrete domes in the world, without any central support columns when their construction started in 1912. They were ordered built by Russian Tsar Nicholas II to shelter the seaplane squadron that was part of Peter the Great’s naval forces. It’s a cavernous space with a seaplane hanging from the ceiling, and where you can actually walk under a submarine. The museum also had a nice café which overlooked the exhibits.

When the weather was inclement or the walking distance too great, we used Uber to get around. The service worked very well for us in Tallinn. Getting to Telliskivi Loomelinnak, the Telliskivi Creative City, from the Lennusadam Sea Plane Harbor was one of those occassions and it worked perfectly.

It’s an old, street-mural covered industrial site that’s been revamped into a hip entertainment and nightlife destination with theaters, galleries, restaurants, and bars. It was a fun place to explore, but I think we skewed the demographics a little bit.

Till next time, Craig & Donna

P.S. We purchased Tallinn Cards to use during our stay in the city and found it to be quite beneficial and cost effective. The card offered access to over 50 museums and attractions, free travel on public transportation, and discounts on sightseeing tours.

Please share my page with your friends