Days earlier, atop the ramparts at Ljubljana Castle, we got our first glimpse of the Kamnik-Savinja Alps, a rugged sawtooth mountain chain that lies north of the city, along the Slovenia – Austrian border in the Solčava region. The range’s three highest peaks, Mt. Grintovec (2,532m), Mt. Jezerska Kočna (2,539m), and Mt. Skuta, (8,307m) still glimmered with snow in early April.

Within the mountain range is Logar Valley, a 7 kilometer (4.3 mile) long alpine glacial valley, surrounded by equally tall sheer summits. Inside the picturesque valley there are trails between Rinka Waterfall (90m – 295ft), the tallest falls in Slovenia, and three other ones that cascade from the mountainsides. It is 1.5 hours from Ljubljana, and we planned to visit the valley during a travel day. Later, backtracking from the mountains, we stayed in Kamnik for two nights before continuing on to Zagreb.

Along our route into the mountains, we stopped to visit the Volčji Potok Arboretum, a large formal garden, only 30 minutes from the city. The park’s tulips beds were in full bloom, and we were just about to purchase our entrance tickets when we were caught in a sudden downpour. Unfortunately, it didn’t look like the weather was going to improve quickly. Crossing our fingers, we hoped the mountains would be storm free, and we continued on.

Past Kamnik, the road slowly rose from the plain into the foothills as it followed the Kamniška Bistrica river, swollen with snow melt. The fresh greenery of spring covered the hillsides. Fruit trees flowered in roadside orchards. Twisting and turning along switchback roads, we drove higher, only to descend into small valleys sheltering tiny hamlets with only a handful of homes and always a church, before ascending again.

A sign pointed the way to Velika Planina, a vast alpine plateau in Slovenia’s Kamnik-Savinja Alps, where traditional transhumance herders continue to graze cattle and sheep seasonally on the high-elevation pastureland from June to September. In planning our trip to Logar, we had considered going to Velika Planina, but to do it justice required a longer visit to the area. It’s one of the dilemmas of planning a trip: what to include, what to pass, what’s research for the future or a simply a teaser, needing a sequel to complete your odyssey.

Eventually the road leveled and followed the Savinja River as it coursed through a narrow gorge, where in certain sections rock ledges loomed ominously low over the road, and we wondered if any campervans had ever lost their roofs along the way.

Signs pointed to the Austrian border, but we turned and sharply climbed to Razgledna Točka pri Klemenči Domačiji, the Lookout Point at the Klemenča Homestead, our destination before entering the valley below. The vantage point overlooking the working farm and mountains is 1,208 meters (3,963 feet) above sea level and is along the Solčava Panoramic Road, a 37km (23mi) scenic route that weaves through spectacular alpine views and past tracs that lead to self-sustaining high mountain farms. The view over the valley surrounded by multiple 2300m (7500ft) mountains, their peaks still hidden by clouds, was stunning.

Like an old-fashioned trading post, the last chance for supplies at the edge of the frontier, was its modern equivalent, a vending machine with dried sausages, cheese rounds, and sandwiches made at the Klemenča Homestead.

Next to it was a whimsical statue of Lintver, a Slovenian folklore dragon associated with the Logar Valley and the Solčava region. Centuries-old legends tell of his role in shaping the area’s valleys and landmarks. Nowadays in Slovenia, the dragon symbolizes the powerful and beautiful forces of nature.

We coasted slowly through the beautiful wide grassy valley to its terminus, the trailhead for the Rinka Waterfall. Though it was only a twenty-minute trek from the parking area, we passed on the opportunity and had a late lunch at Penzion Kmečka Hiša Ojstrica. Their outside deck was open, and we enjoyed a tasty meal while warming in the afternoon sun, if only for a brief moment, before heading to Kamnik for the night. Really, exploring the area in depth requires several days, especially if you want to do any hiking. The park’s website is a good resource for accommodation in the valley and surrounding area.

It was pouring again as we reached Kamnik. Totally unprepared for this deluge, we parked as close to the entrance of Guest House Pri Cesarju as we could. Kindly, the proprietor of the hotel and pizzeria where we were staying ran to assist us with umbrellas as we unloaded our luggage. After a chilly day, it was nice to relax in the comfortably warm restaurant with a glass of local red wine and delicious pizza. The weather the next morning was perfect with a sunny blue sky. A nice change from the cloudy weather pattern that had been over the area for several days.

We drove to Kaminska Pekarna, a hidden gem of a bakery and confectionery, on the side of town nearer Ljubljana. We had discovered it the day before while seeking to satisfy our “drive a little then café’, caffeine cravings. It’s a very simple shop, with only a dozen tables inside, and few outside, under the building’s overhang for the smokers, but it was very busy with local folk, and their sweet and savory pastries were scrumptious. Over our two days in Kamnik we stopped there three times. It was that good, and extremely budget friendly. Parking near the old town is very limited, but it was the shoulder season, and we thought we found a good centrally located spot down a quiet side street. More on that later.

Kamnik is a historic town, one of Slovenia’s earliest, first mentioned in historical records in 1061. By the early 13th century, it had grown into a bustling crafts and market center on the trade route between Hungary and the Adriatic, and it was granted formal town status.

For a time, its importance in Slovenia rivaled that of Ljubljana’s and the town boasted two castles, minted its own coins and was granted a Franciscan monastery, which is still in use. Now in ruins, Stari grad, the old castle, commanded the tall hill across the Kamniška Bistrica river from the village. The tongue of a modern cantilevered viewing deck at the site can been seen from town, but the site was not open in early April when we visited Kamnik. In the center of town Mali grad, the little castle, stands on a small knoll that overlooks what would have been the main routes through the medieval town.

Though this castle was also closed, the path to it led through a nice, shaded park and offered several great views of the red-roofed town with the beautiful Kamnik-Savinja Alps in the distance. A teenage girl, playing hooky from school and enjoying the tranquility of the location, lounged on the castle’s steps, absorbed by her reading.

The warm sunny day called for a gelato, and we stopped at a small café’ with outdoor tables, at the top of Šutna Street. Once the town’s main thoroughfare, it is now a colorful pedestrian lane lined with an assortment of well-preserved homes and guild buildings, dating as far back as the 14th century.

Along the way was the Immaculate Conception Parish Church, a Gothic structure with later Baroque additions, notable for its freestanding bell tower.

At the bottom of the Šutna treet was a life-size silhouetted profile of a distinguished man. The commemorative inscription next to it told the story of Rudolf Maister, a nationalist hero, who was born in a house on this street in 1874. Choosing a military career, he rose to the rank of Major in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in which Slovenia was a province at the time, while serving on the front near Graz, Austria. At the end of World War One, when the “Great Powers” were redrawing the maps of Europe, on his own initiative he disobeyed orders to turn the town over to German-Austria troops. Rallying 4000 loyal Slovene troops to support him he secured Styria, the region south of Graz to be Slovenia’s northern border and part of the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, which united with the Kingdom of Serbia into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which eventually became Yugoslavia. He was an interesting individual who was also recognized for writing two volumes of poetry and starting a military orchestra.

A short distance away in a plaza across from the bus station was Kip Mamuta, a life size bronze sculpture of a woolly mammoth. It commemorates the 1938 discovery of a nearly complete mammoth skeleton, unearthed by workers expanding a bridge, in nearby Nevlje. The site upon further archaeological excavation was determined to be a Paleolithic hunting settlement dated to be around 20,000 years old. The skeleton is on exhibit in the Natural History Museum of Slovenia in Ljubljana. Returning to the car hours later, we realized we had parked down a restricted residential road, which just happened to have its gate up when we drove through earlier that day. Now the automated gate was closed and we were trapped. Waiting patiently until a local resident exited, we followed close behind. Kamnik is a charming small town which we had mostly to ourselves in early April, and we found it very easy to explore fully in a single day. Every September the town hosts the Days of National Costumes and Clothing Heritage, Slovenia’s largest ethnological festival, featuring a grand parade, historical costumes, reenactments, traditional music, dance, regional crafts, and local food.

Finicky weather resumed the next morning as we headed to Cistercijanska Opatija Stična, the Cistercian Abbey of Stična, a 12th century walled monastery along the A2 which we were following to Zagreb, Croatia. It is Slovenia’s oldest operating monastery, though only 14 monks remain, a vast difference from the hundreds that lived there during the Middle Ages and supported the abbey’s vast land holdings and 300 churches in the region. The Cistercian Order is an offshoot of the Benedictine Order, that follows a return to a stricter, simpler monastic life based upon a self-sufficient agrarian orientation, emphasizing austerity, manual labor, solitude, and a balance of prayer and work. During the early years of the monastery, it acted like an agricultural college, where the hard-working monks shared their advanced ideas of crop rotation, irrigation systems, better iron ploughs, selective breeding, and new crop varieties. “They revolutionized the local agriculture,” and contributed to the prosperity of the area by not requiring the local peasants on their granges to pay the annual tithe.

The order’s influence grew with time and the monastery evolved to support a traditional school as well as a music school, herbal pharmacy, and a library where manuscripts were copied. The Stiški Rokopisi, Stična Manuscripts, a famous series of illuminated medieval manuscripts, were written in the mid-1400s by the abbey’s monks, not in Latin as was the tradition, but in the Slovenian language, one of the first such books of the time.

During the Middle Ages the monastery was located on the Slovenia frontier, an area that separated the Christian northern Balkans from the Ottoman Empire. Turkish raids in the area were a common occurrence, and even though the abbey was enclosed within a defensive wall it suffered severe damage during attacks in 1475 and 1529. The abbey continued to prosper until 1784 when Joseph II, the Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of the Habsburg Monarchy, confiscated the lands of monasteries in his realm, and forced monks and nuns into “useful” state-approved roles. The abbey was returned to the Cistercian Order 1898.

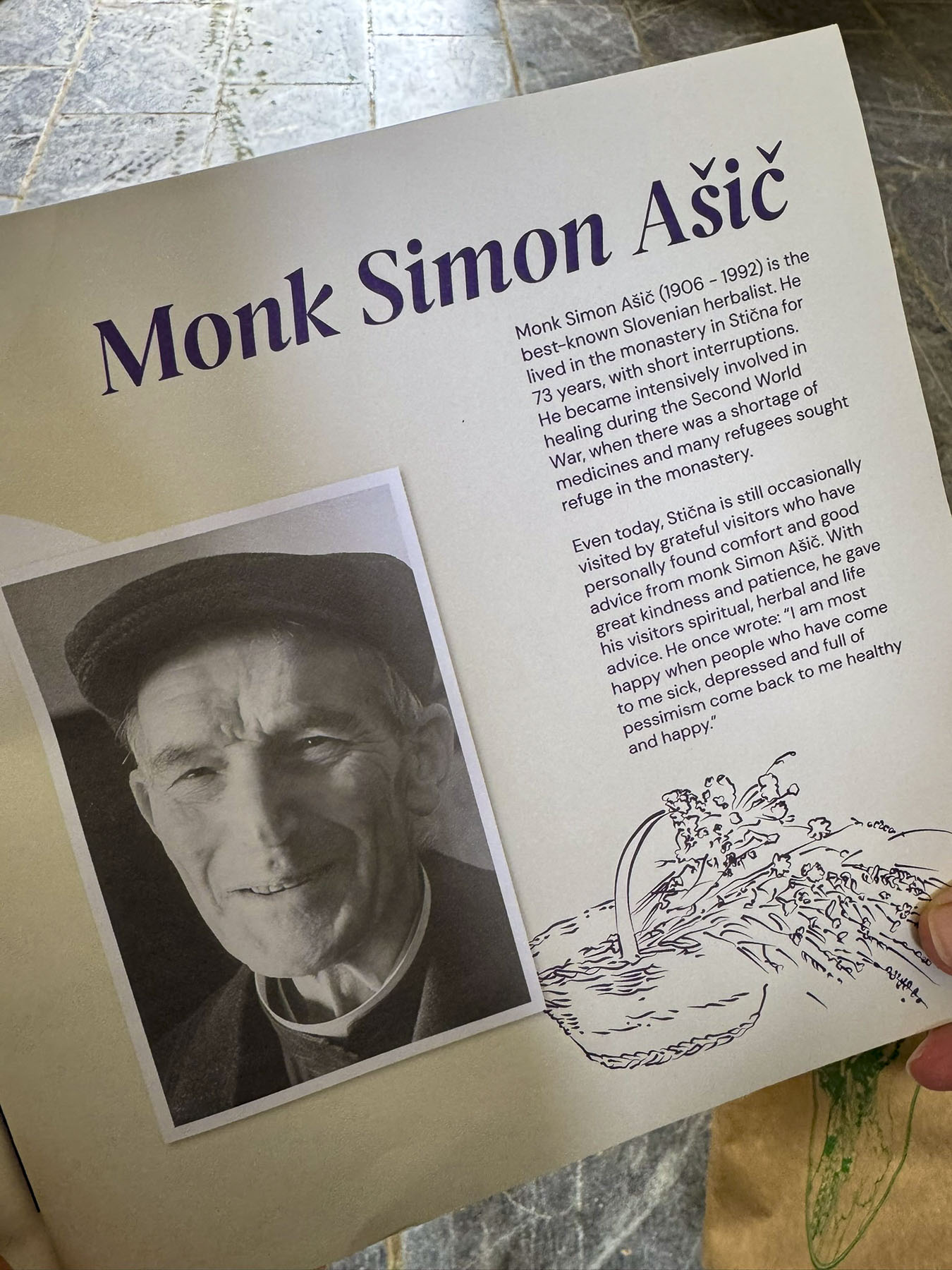

According to the abbey’s records there has been an herbal pharmacy in the monastery since the 15th century, which gathered and used the region’s 400 medicinal plants. This tradition was revived again after 1898 and grew in importance under the direction of Father Simon Ašič (1906-1992). The pharmacy was especially useful during World War II, when many sick refugees sought help from Father Simon. Because of the war, medicines were in short supply, but he was able to help many people with his herbal preparations. Always recording the recipes and results, he published his knowledge in three books. The abbey honored his legacy in 1992 with the founding of SITIK, an herbal products company that sells items prepared according to the original recipes of Father Ašič.

We visitied the abbey’s church, the Our Lady of Sorrows Basilica, once one of the largest in Slovenia. The sanctuary and its cloister were very interesting to explore. Something that we never noticed before in a church was that the confessionals all had small red and green lights on them to indicate which ones were in use.

Regrettably, we missed the tour of the herbal pharmacy, but we did get a small brochure, with some of Father Ašič’s herbal recipes.

Zagreb beckoned. On we went.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna

P.S. Each year in the fall, the village of Stična hosts an arts festival known as Festival Stična.