Moments before we had just flown over a crescent-shaped beach, its thin strip of sand brilliantly separating the rich, inviting blues of the Adriatic Sea from the verdant land of the Albanian coast. What we didn’t expect as we continued our descent was just how mountainous the terrain was. This turned out to be a characteristic of the land that we enjoyed tremendously, after realizing there really aren’t many straight roads in the country, and we’d be spending most of our three weeks in Albania driving winding through its mountains.

It was mid-April and 80F/26C as we sat outside the airport terminal enjoying coffees and the unseasonably warm day. “Do you really think you’ll need the thermal underwear you packed?” Donna chided, with a smile. “We’ll see,” I responded. At the rental car counter across the street, we reviewed our paperwork for the sedan and received the document we needed to drive the car into North Macedonia later on during our trip. “Now you have a city car, don’t drive on any restricted roads. The car has GPS tracking, and you will be fined if you do,” the rental agent explained. While we were aware that Albania did not have the best road infrastructure, we were not aware of road restrictions. We asked for a map showing the forbidden routes, but the agent didn’t have any, nor could he explain all the routes restricted. “Use your best judgement, if it’s a gravel road you should probably avoid it.” Which was not very helpful considering we’ve had lots of experience driving sedans to destinations that folks have said, “you’ll never make it there in that.” The rental agent also related that Albanians are very friendly, but terrible drivers. “Drive defensively!” he warned. We set off. My map app is set to default to no highways, and we followed a route along the perimeter of the airport, which also serves as an Albanian Air Force base, past a row of rusting, derelict MiG fighter jets and, for those aviation enthusiasts, several Antonov An-2, a legendary soviet bi-plane, first flown in 1947.

It was an interesting serpentine route through fields of grazing sheep, the roadway sporadically lined with irises in bloom, flowering orange trees, their scent filling the air, and fig trees laden with newly set fruit. Groups of old men sat at tables playing cards and dominos in vacant lots between mansions and shacks. A psychedelically painted, cold war era tank commanded a park along the road. As it neared the end of the workday and we got closer to Tirana, the roads became congested and wild, with drivers ignoring traffic signs and rules. Often it felt like a game of chicken with oncoming cars zipping into our lane to weave around creatively parked cars. Motorcycles were driven on sidewalks. Numerous speed bumps were the only deterrent preventing the roads from becoming the Daytona 500. In decades past, Tirana was a small town with an ancient footprint. It managed well enough during the country’s communist era when few people had the resources to buy cars. But now the city’s arteries are clogged and it’s ready for permanent gridlock due to the current number of vehicles.

With a car, there is always parking to take into consideration, and we lucked out with Lot Boutique Hotel, located on a narrow side street in the center of Tirana, because it had a small parking lot. The hotel recently had been nicely refurbished and was the perfect base for our wanderings around Tirana, the capital of Albania since 1920. Later after resting – jet lag affects us more as we age – we asked the front desk for recommendations for a traditional Albanian dinner. The young receptionist suggested two places: Ceren Ismet Shehu, a contemporary restaurant located behind the low ancient walls of Tirana Castle, in an area smartly repurposed for shopping and dining. And in the opposite direction Oda – Traditional Albanian Restaurant nearer the traditional daily market. We ended up eating at both on different nights. Each was excellent, but we preferred the simple, laid-back ambiance of Oda, its homestyle cooking, and inexpensive menu.

We’ve enjoyed all the cuisines of the different countries we’ve visited over the years, but surprisingly and refreshingly in Albania we found it very easy to eat a well-balanced meal. French-fried potatoes served automatically in other countries were replaced with the Albanian trilogy of lightly grilled vegetables: peppers, eggplants, and zucchini. And the customary salad of cucumbers, and tomatoes with brined cheese were always good. Grilled meats and fish were expertly prepared, though it was also easy to be a vegetarian sometimes and indulge in a variety of eggplant dishes.

The next morning, we headed to Skanderberg Square. Next to the Et’hem Bey Mosque, built in the early 1800s, but closed during the anti-religion decades of communism, we climbed 90 steps to the top of the 115-foot-tall Clock Tower of Tirana. For decades during the 19th century, the tower was the tallest structure in Tirana. Unfortunately, its once 360-degree view has been hemmed in by the rapid construction of new buildings nearby, but it did have a view over Skanderbeg Square, and the rooftop garden atop Tirana City Hall.

Before its renovation the plaza was a traffic circle with one side hosting a larger-than-life statue of Stalin and the other side a colossal 30ft tall sculpture of Albanian’s paranoid and isolationist communist leader Enver Hoxha. The 1991 student protests on the square, along with other demonstrations across the country, helped bring an end to 46 years of repressive communist ideology and failed economic policies. Stalin’s statue was replaced with a heroic sculpture of Skanderbeg, the 15th century nobleman who rallied Albanians to repel Turkish rule and defeated 13 Ottoman reinvasion attempts.

Hoxha’s statue was replaced with a public toilet. Centuries of conflict and resistance have defined Albania’s history and is reflected in a large, emotive mosaic above the entrance to the National Historical Museum. The Palace of Culture, the Opera & Ballet Theatre, and several government ministry buildings, designed by Italian architects in the 1930s, also line the square. Surrounding the plaza, an array of new construction projects are rapidly changing Tirana’s skyline. The city is having its moment as tourists rediscover this once isolated country, with its paranoia of the west, and shunned by its communist neighbors.

Spotting a belltower through the trees, we headed to the Resurrection of Christ Orthodox Cathedral, built between 1994 and 2002 to celebrate the revival of the Albanian Orthodox Church. It is one of the largest orthodox churches in the Balkans, and is a testament to a renewal of faith that had been outlawed under communism, when churches and mosques were destroyed or desecrated, after Hoxha proudly proclaimed Albania “the world’s first officially atheistic state.” The church is dedicated to the apostle St. Paul, who is believed to have founded the Christian community of Durrës, on the Albanian coast, during the 1st century AD.

We wandered through Rinia Park, a popular green oasis in the center of the city that is known for its Taiwan Musical Fountains, which were unfortunately still winterized when we visited. Afterwards we headed to Rruga Murat Toptani, a shady, treelined pedestrian-only lane with many outdoor cafes and restaurants, offering traditional Albanian food and various international cuisines. We enjoyed a light lunch and a local craft beer under the shade of a sun umbrella at the Millennium Garden.

Bunk’Art2, an eye-opening reminder of the perils of the despotic leader, Enver Hoxha, and the communist police state he created in order to stay in power for forty years, was nearby. It’s a large nuclear bomb-proof bunker in central Tirana, that was connected to various government ministries with tunnels for top officials of the regime to escape through. It was also an interrogation center for the Sigurimi, Albania’s Communist-era secret police force, which spied upon the country’s citizenry, and imprisoned anyone considered an opponent to Hoxha’s policies or authoritarian rule. Across the country 23 prisons were built to imprison 17,900 political prisoners.

Thirty Thousand people were sent to internment camps, and it’s believed over 14,000 were killed, died or worked to death from forced labor, often in dangerous mines. 6,000 are still missing. Often it was not just the individual who was jailed that suffered, but his family would be surveilled for years afterward, and his children would be denied educational opportunities. In Tirana the secret police kept 4,000 people under constant surveillance. The border was heavily patrolled with guard dogs and soldiers authorized to “shoot to kill,” as anyone trying to escape the country was viewed as an enemy of the state, and punishable for treason.

Only the most loyal communist families were allowed to live along the borders. Small villages were forcefully abandoned. The villagers were sent to larger cities were it was easier for the Sigurimi to watch for dissent. The mushroom shaped dome above the entrance to Bunk’Art 2 is symbolic of Hoxha’s paranoia, which manifested as a building campaign to construct an amazing 175,000 + bunkers of various sizes, across the country. Most of them are only big enough for 2-3 people, but they were placed in strategic spots along Albania’s borders to protect the country from foreign invasion, not only from the western powers, but also from Yugoslavia or the USSR. Others were placed in the mountains, farm fields, road intersections and parks, with the intention that Hoxha’s loyalists would man them in a time of crisis. The irresponsible cost of building the bunkers, from which shots were never fired, diverted Albanian funds away from other needed projects and ensured Albania’s position as the poorest country in Europe. The communist government collapsed in 1991, and in the following years, more than 700,00 Albanians emigrated to find better opportunities in Europe or farther afield. Remittances from the Albanian diaspora to family still in the country amount to 14% of Albania’s Gross Domestic Product.

Our eyes needed a moment to adjust after resurfacing from the labyrinth of Bunk’Art 2, but if the construction boom underway in Tirana is an indication, Albania has thrown off the shackles of its communist past and is embracing the prospects of an exciting new future. Heading back to our hotel for a short rest before going to dinner we detoured into the Toptani shopping mall. A nine-story tower dedicated to the “shopping therapy” philosophy of capitalism.

The next day we headed to the New Bazaar market area, only a five-minute walk from our hotel. On the way we passed impromptu sidewalk vendors, their crops and merchandise displayed on blankets or sheets of cardboard on the street, hoping to make sales to folks before they reached the daily market. The covered bazaar centers a plaza surrounded by restaurants, cafes, cheese shops and butcher stores. Under its roof, stands filled the space with vendors selling vegetables, olives, honey, and fruit. Women crocheted wool socks as they waited for customers. We browsed tables piled with rugs, displays of tools, pottery, vinyl records, and books, along with knickknacks, questionable antiques, and surplus Albanian army helmets. The time flew by.

Tirana is a wonderful, midsize cosmopolitan city with a population of 375,000 people, with many parks, tree lined streets, and older buildings, mostly under five stories tall. New high-rise buildings rise from the old neighborhoods across the city. It was an interesting and delightful place to wander around.

We passed ruins of Tirana Castle’s ancient defensive wall, dating to the 1300s, in the park next to Namazgah Mosque, the Great Mosque of Tirana. Completed in 2019, the mosque is currently the largest in the Balkans, and capable of holding 5,000 worshippers. The Muslim community was also persecuted under Hoxha’s anti religion policies, with many religious leaders killed or imprisoned, and 740 mosques destroyed around the country.

Nearby stood the 18th century Ottoman era Tanners’ Bridge, a stone arch across the Lana River that was used by farmers to bring produce into the city and livestock to the butcher shops and tanneries along the river. Farther away we crossed the ETC Bridge, a beautiful pedestrian only walkway over the Lana that is also a free wifi hotspot. The city’s tallest skyscraper, Downtown One, a 37 story, mixed used building with a very distinguishable cantilevered and recessed façade, stood in the background.

Our destination was the Pyramid of Tirana. Planned by Hoxha to be a memorial to his legacy as the Enver Hoxha Museum, covered in gleaming white marble, it opened in 1988, three years after his death. It was designed by Hoxha’s daughter and her husband and at the time of its construction thought to be the most expensive structure ever built in Albania.

Most likely forced prison labor and compulsory labor were used for parts of the project. With the collapse of the country’s last communist regime in 1991, the museum was closed and the space repurposed as a conference center, then a NATO base. It eventually fell into disuse and was vandalized, and its marble covering stripped away. It was finally reincarnated as an IT youth center with classrooms housed in colorful blocks attached on its slope, and 16 staircases leading to the viewing platform atop its 70ft high summit. We climbed to the top and enjoyed the panoramic view.

A short distance away, Hoxha lived in a modest villa in the Blloku neighborhood. It was a secret district during the communist era, with housing reserved for the party elite, with entry forbidden to anyone else, and its road did not appear on any maps.

The Checkpoint memorial stands in the park down the street from his residence and features a bunker, iron mine shaft railings from the infamous Spac prison, and a section of the Berlin Wall. Subtle reminders of the brutality of communism.

For our last day in Tirana, we decided to head to the outskirts of the city to check out Bunk’Art1 before continuing into the mountains to Bovilla Lake. It’s easy to miss the turn into the long single-lane tunnel that leads to Bunk’Art1, an appropriate entrance to explore Albania’s past. After walking through a seemingly forgotten park, we entered a non-descript door in the side of an overgrown slope that hides the extensive maze of corridors and rooms of Hoxha’s secret command center.

We followed a short corridor to the nuclear blast proof doors set in walls 6ft wide, and into a decontamination room. We were five stories underground in the foothills of Dajti Mountain, near the village of Linzë. There are no windows, the lights flicker, and a sign warns the power could go out at any time! It was a massive facility designed to shelter hundreds of Hoxha’s military and communist comrades, for six months, during any war.

In Hoxha’s private quarters, we picked up a phone and listened to a recording of his voice. It was a sparse apartment, more prison cell than home, that lacked any warmth. Obviously, his wife wasn’t consulted. Other rooms displayed vintage equipment and weaponry. The isolation of having to live in this depressing environment would have been psychologically damaging; fortunately, the structure was never needed for war-time use and since 2014 it’s been a museum explaining Albania’s history from liberation by the partisans during WWII through Hoxha’s communist regime. The exhibits use amazing photographs and examples of nationalist propaganda from the country’s archives to great effect. The bunkers’ large meeting hall now hosts concerts and art exhibits. Emerging from the darknes,s an amazing number of different bird calls filled the air, as if welcoming us back to the present.

Following our map’s apps instructions we followed a confusingly serpentine route across the rolling hills outside Tirana before reaching the road, SH53, that led to Bovilla Lake. In the beginning the paved asphalt road was fine, but after a while abruptly changed to graded gravel. Nothing unusual here. Though the farther we traveled into the countryside, we passed fewer cars; rather, we saw large dump trucks, laden with stone from a quarry, headed towards Tirana, filling the air with dust. The road progressively worsened the closer to the quarry we got, as the weight of the trucks pulverized the road surface and created numerous potholes that we had to slowly navigate around. We thought several times about turning back, but we had driven through the Andes in Ecuador, with a sedan, on worse roads. While the going was slow and extremely bumpy, we did eventually make it to the lake, actually a reservoir, and more importantly, Bovilla Restaurant!

The views were astounding! The restaurant was full, with hikers and day trippers from Tirana. The food was good, the beer cold. It was a journey well worth the effort. The car rental GPS tracker did flag us, and we were fined for driving on possibly the worse road in Albania. Fortunately, when we returned the car eighteen days later, after some Albanian-style dickering, we were able to politely negotiate a reduction in the fine.

There were numerous speed traps on the highway leading out of Tirana and most of the times when we passed one, officers were writing out tickets, so we drove well below the speed limit. We were on the way to Berat and it was well past our usual morning coffee break when we spotted the colorful reflection of Bashkia Belsh’s waterfront.

After parking, we strolled along the Belshi Lake shorefront past small shops and some interesting street murals to the town’s boardwalk. Being a weekend, it was full of families with young children. To the delight of many, small rideable electric toy cars were available to rent, along with balloon, ice cream and cotton candy vendors. A small ferry boat took folks on a short cruise around the lake, while others enjoyed the fine weather and strolled along the boardwalk or sat under the umbrellaed tables of the restaurants that lined it.

Closer to Berat we stopped at the Çobo Winery for a tasting that was accompanied by homemade cheeses and locally grown olives. Vintners of white, red, and sparkling wines and raki, they are regarded as one of the best wine producers in Albania.

It’s a small family vineyard with a 100-year tradition spanning four generations, that was sadly interrupted during the communist era, but since the 90s has grown production from 8,000 to 100,000 bottles per year. It was a nice break from our driving, and we enjoyed relaxing under the ancient olives trees in the their courtyard. The wines we tasted were very good and we purchased four to bring home in our luggage, and I’m happy to say they all made it back safely to the states.

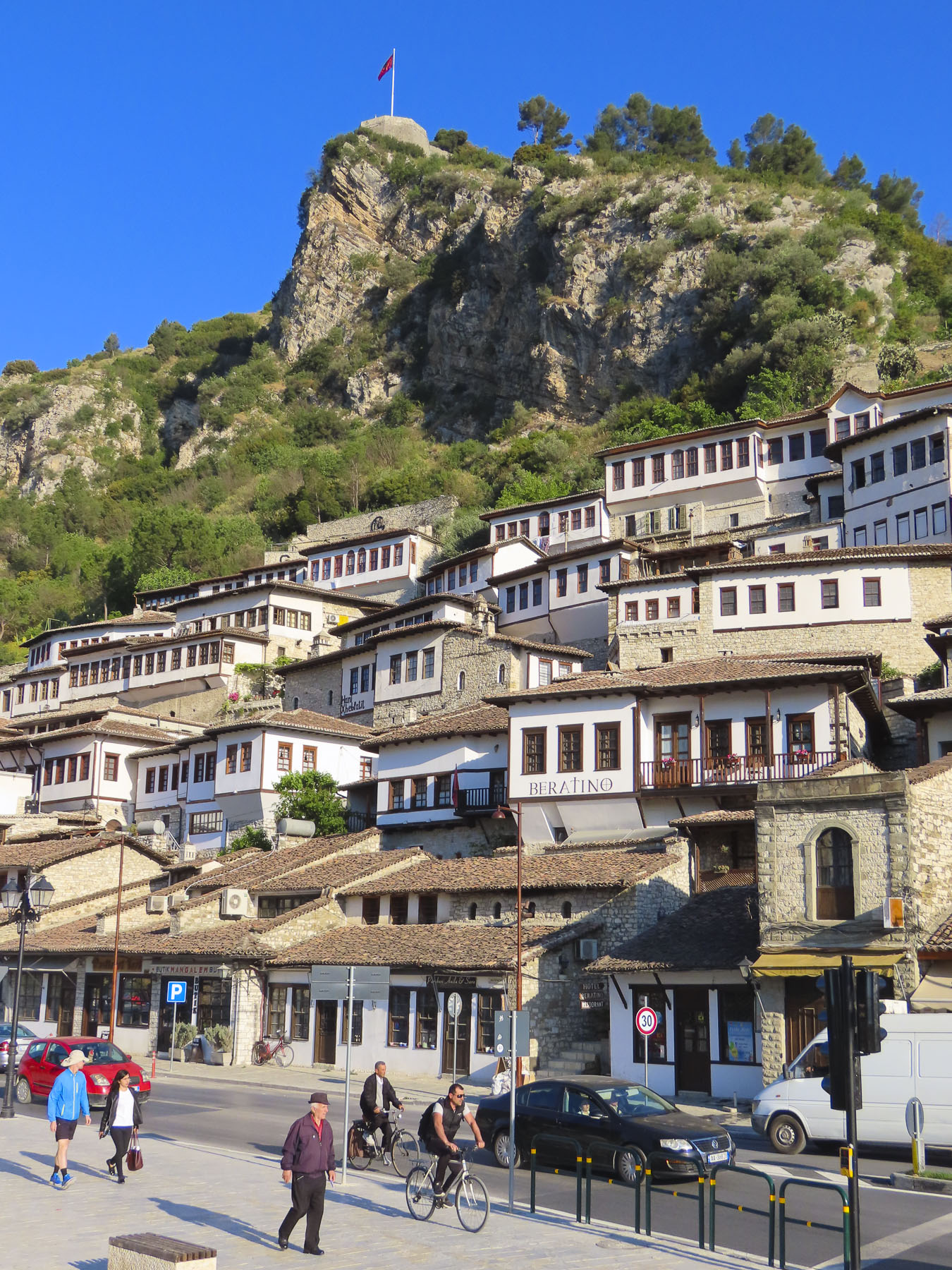

We reached Berat Castle just as the golden hour was approaching. We walked along its cobbled lanes, past homes surprisingly still occupied by about 400 people who live in 13th century citadel. But its history extends much farther back, with Roman records noting capture of the castle in 200BC. Archeological evidence shows the site has been inhabited since 2600-1800BC, making it one of the oldest settlements in Albania.

We worked our way to the overlook above Berat, passing the ruins of the Red Mosque, built in the 1400s after the Ottomans captured Berat, and Kisha e Shën Gjergjit, an orthodox church that’s been neglected since the communist ban on religion.

The panoramic view from the overlook out over Berat, the Osumi River below, and snowcapped 7900ft Mount Tomorri in the distance was stunning. Walking back along the ramparts we enjoyed watching an energetic dog race along the narrow top of the wall, chasing a stick his owner tossed up for him to retrieve multiple times. On the western slope of the castle, between the outer and inner defensive walls, Kisha Shën Triadha, a beautiful red brick, 14th century Byzantine church graces the hillside.

We wanted to stay on the “City of a Thousand Windows,” hillside under the castle, but didn’t want to drag our suitcases too far up the narrow alleys, and we had a car that needed parking. With those considerations in mind The Beratino Hotel fit our requirements perfectly and was great place to stay for two nights. Recently renovated, its stone and woodwork exemplified the best of Albanian craftsmanship. Still the shoulder season, in mid-April, I think were the hotel’s only guests.

Sated from our afternoon wine tasting we walked into the newer part of Berat, now a small city of 47,000, along the pedestrian only Bulevardi Republika, next to Lulishtja park. It had a lovely Neapolitan vibe, with families enjoying the Albanian tradition of “xhiro,” to stroll with friends, relax and enjoy the outdoors after dinner. At a small shop perfectly named Bakery & Food we purchased Burek, a traditional Albanian pastry made with various meat and vegetable fillings. We purchased their spinach burek, reputed to be the best in Berat, some even say the best in Albania. The quest for the best byrek, burek, or borek in Albania might be the catalyst for a return trip to the country. Back on the balcony of our room we enjoyed a glass of wine, and the burek was delicious.

The next morning, we were up early and walked across the suspension bridge linking the old town with the southern Gorica “Little Village,” across the river. From this vantage point we spotted the Kisha e Shën Mehillit, St. Michael’s Church, an Eastern Orthodox Church, built on the steep rock face under the flag that flies above Berat. Thought to have been built in the 14th century, the setting of the red brick and stone church pricked our curiosity and we decided to hike there. The alley that led to the church was only a short distance away from our hotel but wound quickly up the hillside past homes and small inns.

We admired the strength of workers we passed carrying long wooden beams on their shoulders up the hill for a renovation project. We zigzagged higher up the hill, now looking down on the rooftops below, the trail looking like it hadn’t been trodden upon in ages. Unfortunately, the sanctuary was closed, but the views of the church with the river and mountains were well worth our effort.

Later that morning we drove to the small town of Çorovoda, the gateway to the Osumi Canyon. It was a beautiful drive on a bright spring day, and we stopped many times along the way to photograph the scenery.

Before reaching the town, we veered off into the mountains to Ura e Kasabashit “The Bridge of Master Kasa/Kaso,” a classic high arched Ottoman era bridge constructed in 1640 across a wide stream, by the chief engineer of the Ottoman empire, at the time, Albanian architect Reis Mimar Kasemi. It was part of an ancient caravan trade route across the rugged central Albanian mountains, that connected the Adriatic Sea port of Vlorë to Berat, and Korçë before ending in the Greek city, Thessaloniki. Almost 400 years old, it surprised us that it is still standing and we followed some other tourists across it. Farther up the road from the bridge there are more abandoned military bunkers and warehouses, but we were bunkered out after Tirana and chose not to investigate them.

Our “drive a little, then café,” was way behind schedule when we stopped in Çorovoda at Drita e Tomorrit, a restaurant with a small park like setting.

South of Çorovoda there are number of fantastic viewpoints along the Osumi Canyon. The water in the canyon is an amazing turquoise and it’s easy to see why it’s a popular area for rafting and swimming in the summer.

Before returning to Çorovoda for a late lunch we stopped at Gjurma e Abaz Aliut, the Footprint of Abaz Ali, a small roadside shrine believed to have in the solid rock under its canopy an impression of Ali’s foot. Made when the Albania folk hero, with legendary strength and courage, jumped across the Osumi Canyon from this spot. The depression in the stone looked very convincing to me.

Back in Çorovoda we had an early laid-back dinner at Zgara Korçare. It’s a small restaurant with nice owners across the street from where we earlier had coffee. Their mixed grill was delicious and we enjoyed our first tastes of Birra Korça. A good refreshing light beer brewed in Albania since 1928. Gëzuar, cheers!

The next day we headed to the Apollonia Archaeological Park before driving south to the semi-abandoned village of Upper Qeparo, eager to explore the rest of this interesting and stunningly beautiful counrty.

Till next time, Craig & Donna

Heading north on Routes 64 and 6 we drove past fallow farmlands waiting for their Spring tilling, and forgotten industrial sites as we worked our way north towards Stara Planina, the Balkans Mountain range that runs east to west for 348 miles and divides Bulgarian into northern and southern regions.

Heading north on Routes 64 and 6 we drove past fallow farmlands waiting for their Spring tilling, and forgotten industrial sites as we worked our way north towards Stara Planina, the Balkans Mountain range that runs east to west for 348 miles and divides Bulgarian into northern and southern regions.

Turning down the long driveway of the

Turning down the long driveway of the  On a wintry, cloudy afternoon the silhouette of

On a wintry, cloudy afternoon the silhouette of

At the opening ceremony in 1981, tribute was paid to those who had gathered there ninety years earlier. “Let the work of sacred and pure love that was started by those before us never fall into disrepair.” Buzludzha was a huge success and a point of national pride for eight years, hosting communist party congresses and educational events. Schools and businesses booked tours for their students and employees. Foreign delegations were paraded through to witness socialism’s success. But then in 1989 the Berlin Wall fell and communism collapsed like a fighter jet breaking through the sound barrier. The monument to socialism was suddenly ironic, irrelevant and abandoned. In 1999 the security guards protecting it were removed and the building was left open to the public and it was looted. Anything of value quickly disappeared, and the rest was left to vandals and frustrated citizens who were known to take their anger out on the building with sledgehammers or spray paint. The red stars in the tower were shattered by gun shots. Soon the glass skylights broke and water damage from rain and the winter elements hastened its structural decline, and the building was eventually shut tight to protect folks from injury. The day we visited there was a lone security guard, suffering as he made his rounds in the bitter wind, protecting this crumbling modern ruin from a handful of visitors.

At the opening ceremony in 1981, tribute was paid to those who had gathered there ninety years earlier. “Let the work of sacred and pure love that was started by those before us never fall into disrepair.” Buzludzha was a huge success and a point of national pride for eight years, hosting communist party congresses and educational events. Schools and businesses booked tours for their students and employees. Foreign delegations were paraded through to witness socialism’s success. But then in 1989 the Berlin Wall fell and communism collapsed like a fighter jet breaking through the sound barrier. The monument to socialism was suddenly ironic, irrelevant and abandoned. In 1999 the security guards protecting it were removed and the building was left open to the public and it was looted. Anything of value quickly disappeared, and the rest was left to vandals and frustrated citizens who were known to take their anger out on the building with sledgehammers or spray paint. The red stars in the tower were shattered by gun shots. Soon the glass skylights broke and water damage from rain and the winter elements hastened its structural decline, and the building was eventually shut tight to protect folks from injury. The day we visited there was a lone security guard, suffering as he made his rounds in the bitter wind, protecting this crumbling modern ruin from a handful of visitors.

As we continued our journey north through the mountains on Route E85, the picturesque

As we continued our journey north through the mountains on Route E85, the picturesque  Woodcarvers, weavers and other craftspeople dressed in period outfits helped further to transport us to a simpler era at the beginning of the Bulgarian industrial revolution. We visited on a quiet day, but the museum has an extensive twelve-month calendar of events with many festivals listed that would have been nice to observe.

Woodcarvers, weavers and other craftspeople dressed in period outfits helped further to transport us to a simpler era at the beginning of the Bulgarian industrial revolution. We visited on a quiet day, but the museum has an extensive twelve-month calendar of events with many festivals listed that would have been nice to observe.  Traveling along an isolated background road we worked our way towards Sokolski Monastery, known for its cliffside chapel overlooking the northern slope of the Balkan Mountain range. We weren’t disappointed; the church is stunning with its colorful exterior frescoes contrasting with the natural environment surrounding it.

Traveling along an isolated background road we worked our way towards Sokolski Monastery, known for its cliffside chapel overlooking the northern slope of the Balkan Mountain range. We weren’t disappointed; the church is stunning with its colorful exterior frescoes contrasting with the natural environment surrounding it. Built in 1833, the monastery has played an important role in Bulgarian history. During the April Uprising of 1876 eight freedom fighters took sanctuary there. Later captured by the Ottoman army, they were thrown to their deaths from the cliff behind the chapel. The short-lived April Rebellion was brutally repressed, but a year later Russia would help the Bulgarian rebels defeat the Turks at Shipka Pass and begin the march towards freedom. In the courtyard of the monastery an octagon-shaped water fountain was built with eight spouts to commemorate those fallen heroes. Legend states the fountain has never run dry and its cool water holds healing powers.

Built in 1833, the monastery has played an important role in Bulgarian history. During the April Uprising of 1876 eight freedom fighters took sanctuary there. Later captured by the Ottoman army, they were thrown to their deaths from the cliff behind the chapel. The short-lived April Rebellion was brutally repressed, but a year later Russia would help the Bulgarian rebels defeat the Turks at Shipka Pass and begin the march towards freedom. In the courtyard of the monastery an octagon-shaped water fountain was built with eight spouts to commemorate those fallen heroes. Legend states the fountain has never run dry and its cool water holds healing powers.  We made it to Tryavna just in time to have dinner at the restaurant next to our hotel. Enjoying a hot meal after a long chilly day, we were entertained by the waitress trying to keep a determined stray cat from entering the restaurant every time the front door was opened.

We made it to Tryavna just in time to have dinner at the restaurant next to our hotel. Enjoying a hot meal after a long chilly day, we were entertained by the waitress trying to keep a determined stray cat from entering the restaurant every time the front door was opened. Generations of skilled woodworkers have lived in the Tryavna River Valley, turning trees harvested from the deciduous forests on the slopes of the Balkan Mountains into furniture and ornate wood carvings.

Generations of skilled woodworkers have lived in the Tryavna River Valley, turning trees harvested from the deciduous forests on the slopes of the Balkan Mountains into furniture and ornate wood carvings.

Crossing the footbridge over the Tryavna River at the clock-tower, the pleasant whiff of wood smoke came to us on a chilly Spring morning. Large woodpiles are essential in this region and we saw plenty of homes with the winter’s firewood neatly stacked, as we wandered around the village, with its parks filled with sculpture and tulips in bloom.

Crossing the footbridge over the Tryavna River at the clock-tower, the pleasant whiff of wood smoke came to us on a chilly Spring morning. Large woodpiles are essential in this region and we saw plenty of homes with the winter’s firewood neatly stacked, as we wandered around the village, with its parks filled with sculpture and tulips in bloom.

Over the centuries Saint Archangel Michael Church has been reconstructed several times. Its most recent incarnation dates from 1853 when the tall wooden belfry was added. Inside, the interior is richly ornamented with elaborate 19th century woodcarvings and iconography created by members of the Vitan family, famous throughout Bulgaria for generations of skilled artisans. The carved bishop’s throne is an exquisite masterpiece.

Over the centuries Saint Archangel Michael Church has been reconstructed several times. Its most recent incarnation dates from 1853 when the tall wooden belfry was added. Inside, the interior is richly ornamented with elaborate 19th century woodcarvings and iconography created by members of the Vitan family, famous throughout Bulgaria for generations of skilled artisans. The carved bishop’s throne is an exquisite masterpiece. The safest way to order your cup of java in parts of Bulgaria is to ask for a traditional coffee, not wanting to offend anyone by calling it Turkish. The fact is Greek, Albanian, Bosnian, Persian, Turkish andthe same, plus or minus cardamom or a local spice. But here in Tryavna at the Renaissance Café the coffee was brewed on a very traditional sand stove. A shallow pan filled with sand was heated over an open flame, and a long handled, brass cezve was filled with coffee and water, then partially buried in the hot sand to brew. With diligent attendance our coffee was brought to a frothy boil three times before being moved to the top of the sand where it stayed warm while the grounds settled. The ritual of the event definitely enhanced our enjoyment of the brew.

The safest way to order your cup of java in parts of Bulgaria is to ask for a traditional coffee, not wanting to offend anyone by calling it Turkish. The fact is Greek, Albanian, Bosnian, Persian, Turkish andthe same, plus or minus cardamom or a local spice. But here in Tryavna at the Renaissance Café the coffee was brewed on a very traditional sand stove. A shallow pan filled with sand was heated over an open flame, and a long handled, brass cezve was filled with coffee and water, then partially buried in the hot sand to brew. With diligent attendance our coffee was brought to a frothy boil three times before being moved to the top of the sand where it stayed warm while the grounds settled. The ritual of the event definitely enhanced our enjoyment of the brew. We only just scratched the surface of this lovely country. There’s so much to see here, especially in its vast countryside. Hopefully one day we’ll get a chance to return.

We only just scratched the surface of this lovely country. There’s so much to see here, especially in its vast countryside. Hopefully one day we’ll get a chance to return.

Just outside Old Town Plovdiv,

Just outside Old Town Plovdiv,

At just over a mile long the pedestrian mall in the center of Plovdiv is the longest in Europe, running from the Stefan Stambolov Square along Knyaz Alexander I, and Rayko Daskalov Street before ending at the footbridge lined with shopping stalls that crosses the Maritza River.

At just over a mile long the pedestrian mall in the center of Plovdiv is the longest in Europe, running from the Stefan Stambolov Square along Knyaz Alexander I, and Rayko Daskalov Street before ending at the footbridge lined with shopping stalls that crosses the Maritza River.

But the jewel of the mall area was the curved ruins of the Ancient Stadium of Philipopolis, with its fourteen tier seating area, unearthed in 1923. Situated below street level and surrounded by modern buildings at Dzhumaya Square, the ruins provided a dramatic juxtaposition of the ancient and contemporary, where you can actually see the layering of history and how the city was built over earlier civilizations. From this excavated section, archeologists have determined that the stadium was a huge 790 feet long and 165 feet wide and could seat nearly 30,000 spectators.

But the jewel of the mall area was the curved ruins of the Ancient Stadium of Philipopolis, with its fourteen tier seating area, unearthed in 1923. Situated below street level and surrounded by modern buildings at Dzhumaya Square, the ruins provided a dramatic juxtaposition of the ancient and contemporary, where you can actually see the layering of history and how the city was built over earlier civilizations. From this excavated section, archeologists have determined that the stadium was a huge 790 feet long and 165 feet wide and could seat nearly 30,000 spectators. Across the square the Dzhumaya Mosque is the main Friday Mosque for Muslims in Plovdiv. Constructed in 1421, it replaced an earlier mosque built in 1363 on the foundations of a Bulgarian Church destroyed during the Ottoman conquest. It is one of the oldest and largest Muslim religious buildings in the Balkans. At the café in front of it we enjoyed some sweet Turkish tea and pastries in the warm afternoon sun.

Across the square the Dzhumaya Mosque is the main Friday Mosque for Muslims in Plovdiv. Constructed in 1421, it replaced an earlier mosque built in 1363 on the foundations of a Bulgarian Church destroyed during the Ottoman conquest. It is one of the oldest and largest Muslim religious buildings in the Balkans. At the café in front of it we enjoyed some sweet Turkish tea and pastries in the warm afternoon sun.

In the airport, at the tourist information kiosk, multiple large screen tv’s played flashy videos promoting Bulgaria’s culture, tourism, and natural beauty. We asked the woman staffing the desk for a map of Sofia and directions on how to transfer into the city. “Follow the line,” she snapped. Not fully understanding I asked again. “Follow the line!” she barked firmly a second time. She scowled in the direction of the arrows painted on the floor and turned away. Her previous career, I’m speculating, was a prison guard in the now closed gulags. She was obviously better suited commanding prisoners to “assume the position” than to being the first friendly face welcoming visitors to her country. I’m sure she was hiding handcuffs and would have used them if I asked another question. But that’s how it was, one day you’re communist and the next day you’re taking customer service courses and trying to embrace a free market economy. And for some the promise of a better life hasn’t been realized. Later, one of our hosts would express, “some folks prefer the old way, they’re still communists.” “Come and keep your comrade warm,” another refrain from the Beatles song, didn’t ring true. We weren’t feeling the love just yet. Aside from that rocky start, we had very enjoyable time in Bulgaria.

In the airport, at the tourist information kiosk, multiple large screen tv’s played flashy videos promoting Bulgaria’s culture, tourism, and natural beauty. We asked the woman staffing the desk for a map of Sofia and directions on how to transfer into the city. “Follow the line,” she snapped. Not fully understanding I asked again. “Follow the line!” she barked firmly a second time. She scowled in the direction of the arrows painted on the floor and turned away. Her previous career, I’m speculating, was a prison guard in the now closed gulags. She was obviously better suited commanding prisoners to “assume the position” than to being the first friendly face welcoming visitors to her country. I’m sure she was hiding handcuffs and would have used them if I asked another question. But that’s how it was, one day you’re communist and the next day you’re taking customer service courses and trying to embrace a free market economy. And for some the promise of a better life hasn’t been realized. Later, one of our hosts would express, “some folks prefer the old way, they’re still communists.” “Come and keep your comrade warm,” another refrain from the Beatles song, didn’t ring true. We weren’t feeling the love just yet. Aside from that rocky start, we had very enjoyable time in Bulgaria.  The line led to a modern subway station adjacent to the airport terminal and for 1.60 BGN, about 90¢ USD, we rode the

The line led to a modern subway station adjacent to the airport terminal and for 1.60 BGN, about 90¢ USD, we rode the We emerged onto the pedestrian only Vitosha Boulevard filled with folks enjoying a warm Spring day and an incredible vista of Vitosha Mountain towering over the city. Inviting outdoor cafes lined the street and we quickly chose which one we’d return to after meeting our Airbnb host. We stayed on Knyaz Boris just two blocks parallel to Vitosha Boulevard and as majestic as the pedestrian mall was, the side streets, though tree lined and harboring small shops and restaurants, were slightly dismaying with wanton graffiti tags on every apartment building door and utility box. There was a lack of pride in ownership.

We emerged onto the pedestrian only Vitosha Boulevard filled with folks enjoying a warm Spring day and an incredible vista of Vitosha Mountain towering over the city. Inviting outdoor cafes lined the street and we quickly chose which one we’d return to after meeting our Airbnb host. We stayed on Knyaz Boris just two blocks parallel to Vitosha Boulevard and as majestic as the pedestrian mall was, the side streets, though tree lined and harboring small shops and restaurants, were slightly dismaying with wanton graffiti tags on every apartment building door and utility box. There was a lack of pride in ownership.  The idea that’s it’s not my responsibility is a leftover from the communist era, when the government owned and was responsible for everything. The front door to our building was no different, but our third-floor walkup apartment was an oasis with a sun-drenched living room and tiny balcony that we would call home for a month. And to our delight, but to our waistlines’ detriment, there was a baklava bakery across the street!

The idea that’s it’s not my responsibility is a leftover from the communist era, when the government owned and was responsible for everything. The front door to our building was no different, but our third-floor walkup apartment was an oasis with a sun-drenched living room and tiny balcony that we would call home for a month. And to our delight, but to our waistlines’ detriment, there was a baklava bakery across the street!  Long at the crossroads of expanding empires, Bulgaria has had a contentious past with Thracian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman and communist influences. The First Bulgarian Empire, 681-1018, has been deemed the Golden Age of Bulgarian Culture, with the adoption of Christianity as the official religion in 865 and the creation of the Cyrillic alphabet. Independent for only short periods of time during the medieval age, the National Revival period between 1762-1878 brought Bulgaria to finally throw off the yoke of Ottoman domination that had lasted from 1396. Sadly, there were only six decades of self-government before the proud people of Bulgaria became a satellite regime of communist Russia at the end of WWII and fell behind the Iron Curtain.

Long at the crossroads of expanding empires, Bulgaria has had a contentious past with Thracian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman and communist influences. The First Bulgarian Empire, 681-1018, has been deemed the Golden Age of Bulgarian Culture, with the adoption of Christianity as the official religion in 865 and the creation of the Cyrillic alphabet. Independent for only short periods of time during the medieval age, the National Revival period between 1762-1878 brought Bulgaria to finally throw off the yoke of Ottoman domination that had lasted from 1396. Sadly, there were only six decades of self-government before the proud people of Bulgaria became a satellite regime of communist Russia at the end of WWII and fell behind the Iron Curtain. Today Sofia is transforming itself into one of the most beautiful, cosmopolitan cites in Europe with its pedestrian malls, extensive park system and tram lines that weave throughout the city. But the past is always present and just around the corner in Sofia. Walking north along Vitosha past the end of the pedestrian mall there is a three block stretch that displays a vast stretch of that history on the way to the Central Market Hall, where we were headed to stock our pantry. We got sidetracked.

Today Sofia is transforming itself into one of the most beautiful, cosmopolitan cites in Europe with its pedestrian malls, extensive park system and tram lines that weave throughout the city. But the past is always present and just around the corner in Sofia. Walking north along Vitosha past the end of the pedestrian mall there is a three block stretch that displays a vast stretch of that history on the way to the Central Market Hall, where we were headed to stock our pantry. We got sidetracked. Seven millennia ago, put down the first foundations of what we now call Sofia. The construction of Sofia’s modern subway system in the 1990’s revealed multiple layers of antiquity and many of the amazing artifacts unearthed are displayed, in museum cases, on the subway platforms in the Serdika station and National Archeology Museum nearby.

Seven millennia ago, put down the first foundations of what we now call Sofia. The construction of Sofia’s modern subway system in the 1990’s revealed multiple layers of antiquity and many of the amazing artifacts unearthed are displayed, in museum cases, on the subway platforms in the Serdika station and National Archeology Museum nearby.

Tragically in a 1925 bombing, the Bulgarian Communist Party attempted to kill the King of Bulgaria and other members of the government who were attending a funeral at this church – one hundred-fifty people died, and the cathedral’s dome was razed. Excavations behind the church in 2015 uncovered early ruins and a treasure of 3,000 Roman silver coins from the 2nd century AD.

Tragically in a 1925 bombing, the Bulgarian Communist Party attempted to kill the King of Bulgaria and other members of the government who were attending a funeral at this church – one hundred-fifty people died, and the cathedral’s dome was razed. Excavations behind the church in 2015 uncovered early ruins and a treasure of 3,000 Roman silver coins from the 2nd century AD.

It ends just short of Banya Bashi, an Ottoman mosque built in the 16th century. The towering statue of St. Sofia is also visible just beyond the subway station. Ancient walls found during the renovation of the Central Market Hall can also be seen in the lower level of that building.

It ends just short of Banya Bashi, an Ottoman mosque built in the 16th century. The towering statue of St. Sofia is also visible just beyond the subway station. Ancient walls found during the renovation of the Central Market Hall can also be seen in the lower level of that building. Nearby the oldest building in Sofia, the Church of Saint George, built by the Romans in the 4th century, has early Christian frescoes which were painted over by the Ottomans when it was used as a mosque, but they were rediscovered in the 1900s and restored. It stands surrounded by modern buildings in a courtyard behind the President of the Republic of Bulgaria building, within earshot of the Changing of the Guard.

Nearby the oldest building in Sofia, the Church of Saint George, built by the Romans in the 4th century, has early Christian frescoes which were painted over by the Ottomans when it was used as a mosque, but they were rediscovered in the 1900s and restored. It stands surrounded by modern buildings in a courtyard behind the President of the Republic of Bulgaria building, within earshot of the Changing of the Guard.

In the crypt of the cathedral a small, state of the art museum showcases the development of Bulgarian orthodox iconography over the centuries.

In the crypt of the cathedral a small, state of the art museum showcases the development of Bulgarian orthodox iconography over the centuries.  Nearby, the five gilded spires of the Russian Church, officially known as the Church of St Nicholas the Miracle-Maker, can be seen from the steps of Cathedral Saint Aleksandar Nevski. Built in 1914 on the site of a mosque that was torn down after the liberation of Bulgaria, it served has the official church for the Russian Embassy and the Russian community in Sofia. The religious murals that cover the interior of the church were created by Vasily Perminov’s team of talented icon painters, who were also responsible for the iconography in Cathedral Saint Aleksandar Nevski. Darkened by decades of candle smoke, the fresco paintings in the dome were restored in 2014.

Nearby, the five gilded spires of the Russian Church, officially known as the Church of St Nicholas the Miracle-Maker, can be seen from the steps of Cathedral Saint Aleksandar Nevski. Built in 1914 on the site of a mosque that was torn down after the liberation of Bulgaria, it served has the official church for the Russian Embassy and the Russian community in Sofia. The religious murals that cover the interior of the church were created by Vasily Perminov’s team of talented icon painters, who were also responsible for the iconography in Cathedral Saint Aleksandar Nevski. Darkened by decades of candle smoke, the fresco paintings in the dome were restored in 2014.

In 2001 an early Christian mausoleum was unearthed near the American Embassy and it’s fantastic that things are still being discovered in 2019.

In 2001 an early Christian mausoleum was unearthed near the American Embassy and it’s fantastic that things are still being discovered in 2019.

Fortifying the high ground was the rule centuries ago and the last remnant of Castelo e Muralhas Castelo Branco, the white castle, still commands the skyline above the old historic district of the town. Much isn’t known of the history of Castelo Branco before 1182, when it is first mentioned in a royal document decreeing land to who else, but those prolific castle builders the Knights Templar. Only 18km (11 miles) from the Spanish border, the fortified village quickly grew into an important center of commerce and line of defense to protect the Portuguese frontier. Today only two towers and a wide section of the ramparts are all that remained to remind us of this once mighty fortress and walled city. Igreja de Santa Maria do Castelo is thought to be the first church built in the village, when it was constructed within the castle walls on the foundations of a ruined Roman temple. The church had a turbulent history: destroyed in 1640 during the Portuguese Castile war, burnt down in 1704 and then used by the French as a stable when they invaded. It was left in ruins until it was rebuilt in the 19th century. It now sits peacefully in the park, atop the hill, with a view of the surrounding countryside.

Fortifying the high ground was the rule centuries ago and the last remnant of Castelo e Muralhas Castelo Branco, the white castle, still commands the skyline above the old historic district of the town. Much isn’t known of the history of Castelo Branco before 1182, when it is first mentioned in a royal document decreeing land to who else, but those prolific castle builders the Knights Templar. Only 18km (11 miles) from the Spanish border, the fortified village quickly grew into an important center of commerce and line of defense to protect the Portuguese frontier. Today only two towers and a wide section of the ramparts are all that remained to remind us of this once mighty fortress and walled city. Igreja de Santa Maria do Castelo is thought to be the first church built in the village, when it was constructed within the castle walls on the foundations of a ruined Roman temple. The church had a turbulent history: destroyed in 1640 during the Portuguese Castile war, burnt down in 1704 and then used by the French as a stable when they invaded. It was left in ruins until it was rebuilt in the 19th century. It now sits peacefully in the park, atop the hill, with a view of the surrounding countryside.