Large swathes of sunlight graced the rolling landscape of the northern highlands as the plane began its descent toward Inverness. The change in weather was welcomed after a delayed flight from London put us two hours behind schedule, and we were landing in Inverness after all the car rental agents in the airport closed at 5 pm. It was a situation we didn’t realize until we departed London, and in the air. Being from the states where the airports stay open extremely late, we hadn’t made any contingency plans for this unexpected delay, and it, along with fretting about driving on the left side of the road, filled us with anxiety as the last car hire bus to Arnold Clark’s offsite lot ran at five. While waiting at baggage claim we somehow connected with another couple on our flight with the same dilemma and shared our worries. An audible sigh of relief was released when to our surprise an Arnold Clark agent was waiting for all of us, holding a placard with our names on it, as we exited the baggage claim area. Our cars were parked for us outside. The agent was absolutely wonderful, and prevented a rough start to our vacation. He also recommended an excellent restaurant, The Snow Goose, just minutes from the airport. Arnold Clark really went the extra mile for us, and we thanked the agent profusely.

I think driving away from any new airport is the most dangerous part of many trips. Horns blared. Stay left, look right was our mantra. Lunch had happened many hours earlier, and with a two-hour drive south to Pitlochry ahead of us, we decided to stop for dinner. First impressions of a new destination are important, and ours were pleasantly exceeded when we stopped at The Snow Goose, first with a riotous display of color from beautiful hydrangeas that lined the walkway. Then the realization that customers’ dogs are welcomed inside restaurants, pubs too, and just want the chance to wag their tails, and have their heads rubbed. This is something totally alien to the restaurant scene in the United States, but it was very nice, and all the dogs were so well behaved. Lastly, the food was great. Beetroot and Pumpkin Seed Arancini to start, followed by Seared Sea Bass and Pan-Roasted Lamb.

Grand expanses of heather covered the hillsides between forests of pine, while tufted vetch in infinite shades of purple and pink carpeted the edge of the road.

After a little difficulty finding the driveway, the hosts, a husband-and-wife team, of the Craigroyston House & Lodge greeted us as dusk was descending, and showed us our room. It was late, a friendly “See you in the morning. Good night,” was all that was called for. The Full Scottish breakfast – bacon, sausage, black pudding, haggis, mushrooms, tomatoes, and egg was a delicious as the dinner the evening before. The small medallion of haggis that accompanied this breakfast was the perfect introduction to the national dish of Scotland that’s made with minced liver, heart, and lungs of a sheep, and mixed with mutton suet, oatmeal, then seasoned with onion, cayenne pepper, and other spices. It really was very good, and we enjoyed it many times with breakfast during our stay in the Highlands.

The Craigroyston House is a small eight-room inn, with a beautiful, terraced garden, conveniently located one block away from Pitlochry’s main thoroughfare. Colorful hanging baskets hung from many shops, and brightened a gray morning. The weather report for the week ahead showed the possibility of rain every day.

Shopkeepers apologized for the unusually cold and rainy August Scotland was having. We soon realized, though, that those dreary mornings often gave way to brilliantly sunny afternoons. Heading back to the inn we stopped at Heathergems, a shop that turns highly compressed heather stems into unique jewelry. If you are looking for a souvenir this is definitely a place to consider.

The plan for the day was to drive to the village of Dunkeld. Then continue to Drummond Castle to wander around its formal garden, before ending the day in Edinburg.

By late morning we arrived in Dunkeld and spent a while searching for parking close to the town’s ancient cathedral. It had started to rain, and it became a futile task competing with other tourists also wanting to find a parking space in the small village. We opted to park along the Tay River at the Tay Terrace Car Park, only a short walk away from the cathedral. The village has a long history that has always been tied to the early church in Scotland since 730AD, when Culdee Monks, Celtic missionaries, built a monastery there. One hundred and twenty years later the small village’s influence mushroomed when the first King of the newly united Picts and Scots, Kenneth I MacAlpin, moved the relics of Saint Columba from the Hebrides’ Isle of Iona to Dunkeld, to prevent their desecration by Viking raiders. Columba was a 6th century Irish missionary who founded an abbey on Iona, and is credited with spreading Christianity in Scotland.

In the mid 1200’s construction of a grand cathedral started above the ruins of the ancient Culdee Monastery. It was finished 250 years later in 1501, but only served in all its glory for sixty years before the altar and nave of the cathedral were seriously damaged when the roof of the cathedral was destroyed during the Protestant Reformation. At this time, the Scottish Parliament outlawed Catholicism and ended centuries of Papal authority over Scotland, which fundamentally altered the country’s cultural and social landscape. “Churches were to be stripped of their idolatrous religious art and decoration and then whitewashed, so that only God and Christ would be worshipped, and not their images, or images of the saints.”

The choir end of the cathedral was reroofed in 1600 to serve as the parish church or kirk, but was again damaged, when most of Dunkeld was destroyed in the Jacobite Rebellion of 1689. Over time the village slowly re-emerged as a market town, and supported weaving, candle-making, tanning and brewing businesses.

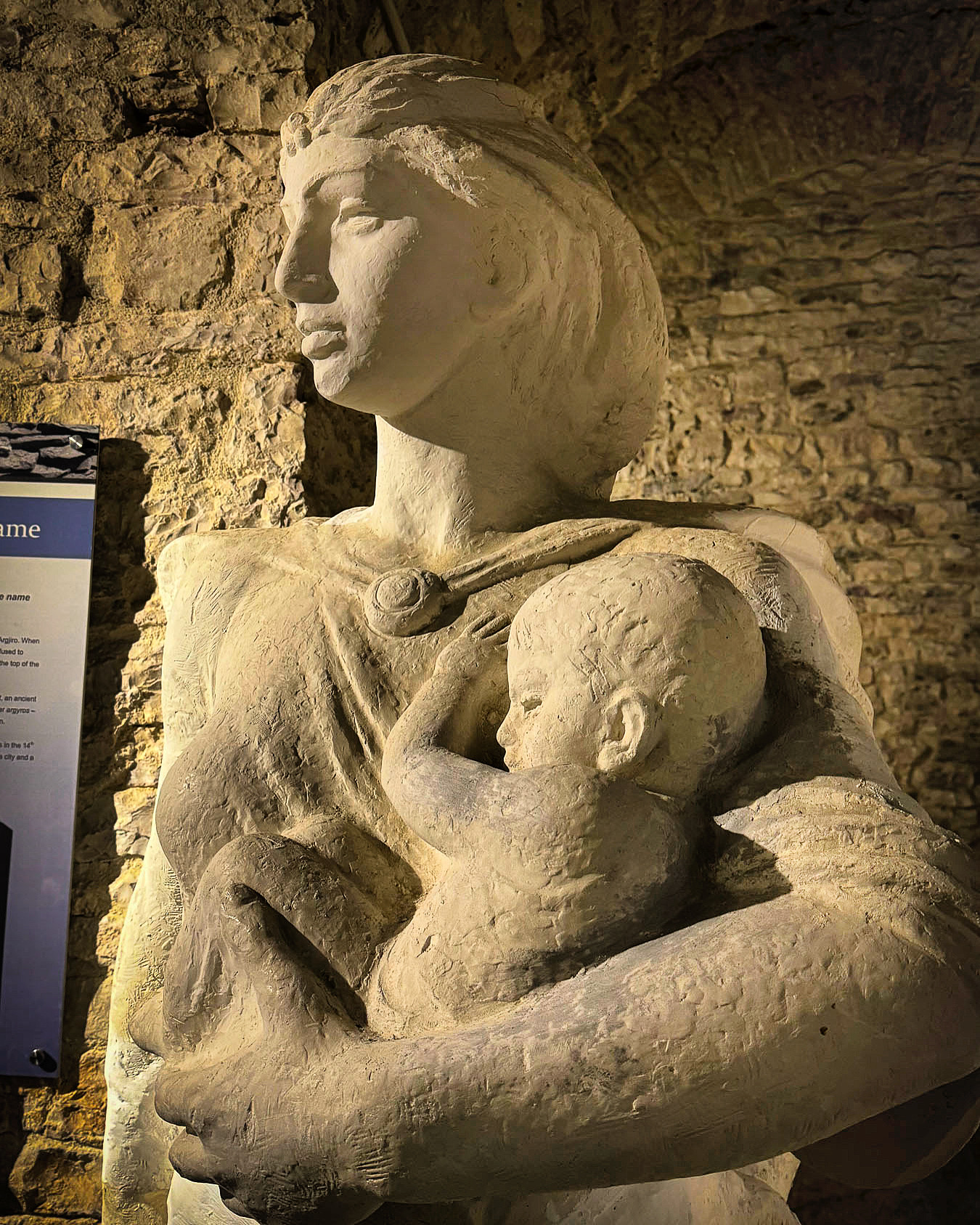

Off to the side and behind the altar in the “new” parish kirk, there is an interesting small museum with sculptures and tombs. Nearby in front of the cathedral, in the town’s old market square, there is an elegant stone fountain detailed with carvings of animals, birds, and Masonic symbols. It’s dedicated to George Augustus Frederick John, the 6th Duke of Atholl, and a Grand Master of the Scottish Masons, who brought piped water to the village in the mid 1800’s.

Dunkeld, with its many nooks and crannies and architectural details, was a delight to explore. When it started to rain harder, we sought refuge and lunch at Palmerstons, a small café busy with wet tourists. They served a great hearty lunch and good coffee at a fair price.

Centuries ago a ferry was the only way to cross the Tay river to Dunkeld’s sister village, Little Dunkeld, but it was extremely dangerous when the river was running high and fast. So, with great relief and fanfare, a stone bridge across the river was built in 1809. It’s a simple seven-arch construction that has withstood the test of time. It was designed by Thomas Telford, who is more famously known for engineering the 60-mile long Caledonian Canal which joined Inverness to Fort William, essentially connecting the North Sea to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Legacy of Beatrice Potter drew us across the bridge. The author and illustrator of the widely loved children’s books, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, The Tale of Jemima Puddle Duck and The Tale of Tom Kitten spent many summers of her youth vacationing in Dunkeld and exploring the flora and fauna along the River Tay. A charming park featuring small bronze sculptures of her animal characters along a pathway through the woods is dedicated to her memory.

We abandoned the highways and drove southwest through rolling hills along the famously narrow single-track roads of the highlands. The lanes, often lined with stone walls and fencing, allow two-way traffic, but in order to pass an oncoming car one vehicle has to pullover into a small bump-out called a Passing Place. These are well marked and spaced along the country roads, but you need to be on the lookout for approaching cars, as the protocol is for drivers to pull into the closest Passing Place on their side of the lane and wait for the other vehicles to pass. It took some getting used to. Surprisingly, the speed limit on these single-track roads is 60 mph, but we were only comfortable driving at half that speed. It was also important to be on the lookout for any stray farm animals that might have escaped their pasture, or equestrians, and those adorable tiny hedgehogs that wander across the road. Fortunately, no one was behind us when Donna, my eagle-eyed co-pilot shouted, “STOP!” and was out of the car in a flash to usher a hedgehog across the lane. The one big drawback is that you are not allowed to use the Passing Places to park and take pictures of the beautiful scenery.

Just beyond Crieff we turned off the main road and followed a mile long driveway through a tunnel of ancient trees to Drummond Castle to see its Renaissance style formal gardens. It was still cloudy, but there was a hint of blue sky on the horizon as we stood in the castle’s courtyard above the gardens and readied ourselves for the walk down a long set of wide stairs into the flowering oasis, when suddenly a cloud burst above our heads and drenched us.

We scrambled back to the ticket office and asked for a refund, as we had only been there for a few minutes, but none was offered. That patch of blue above still teased us. We waited, and the sky brightened. The gardens were spectacular, as if the flowers had received a heavenly command to overcompensate for the bleak weather.

The castle’s original 15th century six-story stone keep still stands, but only the lower 2 floors are open to the public. The other chateau-like buildings were added in the 1600’s and are the private rooms of the Drummond family, which remarkably still owns the place after 500 years. In 1842 Queen Victoria is believed to have planted a beech tree in the garden, and understatedly praised the grounds in a letter to a friend, “Prince Albert and I walked in the garden, which is really very fine, with terraces, like an old French garden.”

After climbing back up the stairs we ordered two cappuccinos to ward off the day’s chill from a barista, boredly pacing in a coffee trailer parked in the courtyard. “Do the folks who own this live here?” I asked. “No, they have other castles but visit occasionally.” We walked away with a new realization about one-percenters.

As we headed to Edinburg the sky finally cleared. Originally, I had planned our route to follow the M90 south and cross the Firth of Forth bridge into the city. But somehow, we ended up much further west, and were totally surprised when the 100ft tall steel Kelpies, shining brilliantly in the afternoon, towered above the tree line along the side of the highway. We had planned to stop there after visiting Edinburgh, but with the afternoon weather now perfect we seized the day and changed our plans. These equestrian statues are located in Helix Park at the confluence of the Clyde Canal and the River Carron. The steel horseheads are the largest in the world, and were created by the internationally acclaimed Scottish sculptor, Andy Scott. They are based on Scottish folklore where a kelpie is a dangerous shape-shifting water spirit that appears on land as a horse, who entices its unsuspecting victim to ride on their backs, only to be sped away to a watery grave.

It was a great second day in Scotland. On to Edinburgh!

Till next time, Craig & Donna

P.S. Scottish weather is notoriously fickle and changes dramatically throughout the day. Being prepared to layer up or down and having proper waterproof rain gear and footwear was essential. We invested in some Gore-Tex rain jackets and were delighted that they kept us totally dry.