With a sharp dog-leg turn to the left we followed the E751 across the bridge above the Dragonja River and crossed into Slovenia from Croatia, leaving the cerulean blues of the Adriatic behind us as we headed into the mountainous “Green Heart of Europe.” Across from each other at an intersection, competing ladies had cartons of fresh picked Spring strawberries piled high on roadside tables.

Ljubljana, Slovenia is only 202 km (126 mi) from the harbor town of Pula, Croatia, a fast 2.5-hour trip, on excellent roads, if you drive straight through. But we had chosen several spots to explore along the way, and we’d be happy if we arrived in Ljubljana before sunset.

With a population of just over two million people, Slovenia’s countryside is wonderfully underdeveloped, and rich with pristine landscapes of forests and farmlands. A fresco of dancing skeletons in Cerkev sv. Trojice, the Church of the Holy Trinity, in the rural village of Hrastovlje was our first destination. Along the way a cluster of homes in the hamlet of Podpeč, seemed to cling for dear life on a steep slope below a karst cliff face, on top of which stood Obrambni Stolp Podpeč, a tall 11th century Venetian watch tower, which is said to have outstanding views across Slovenian Istria region all the way to the Bay of Koper and the Gulf of Trieste.

A few minutes later, after driving between buildings along a very narrow farm lane, where we were sure we would have lost the side mirrors on the car if we hadn’t pulled them in, we were standing in front of the locked iron gate of Cerkev sv. Trojice. A placard picturing the fresco we hoped to see listed a telephone number to call. We dialed, no answer. It was a beautiful Spring Saturday; surely, we thought, the site must be open. Fortunately, there was a small taverna, the Gostilna Švab, nearby that was in the process of opening for lunch. Inquiring about the church, the proprietress was very helpful in calling the gentleman, who she assured us would be there shortly. Pouring two coffees she shared, “he’ll be there by the time you finish these.” The coffee was very good, alleviating the chill of the morning as we sat outside on the tavern’s terrace, and it perfectly satisfied our “drive a little, then café, ritual.

By the time we entered the courtyard of the fortress church several other visitors had arrived, and we spent a few minutes admiring the small church and its belltower. The ancient church, built on a rise above rolling fields, is believed to have been built between the 12th and 14th centuries, with the ramparts and corner towers added later in the 16th century to repel Turkish attacks along this frontier region as the Ottoman Empire fought to expand its control across the Balkan region farther into the territory of the Habsburg Empire, but didn’t succeed. It’s not remembered when the clock was added to the belltower.

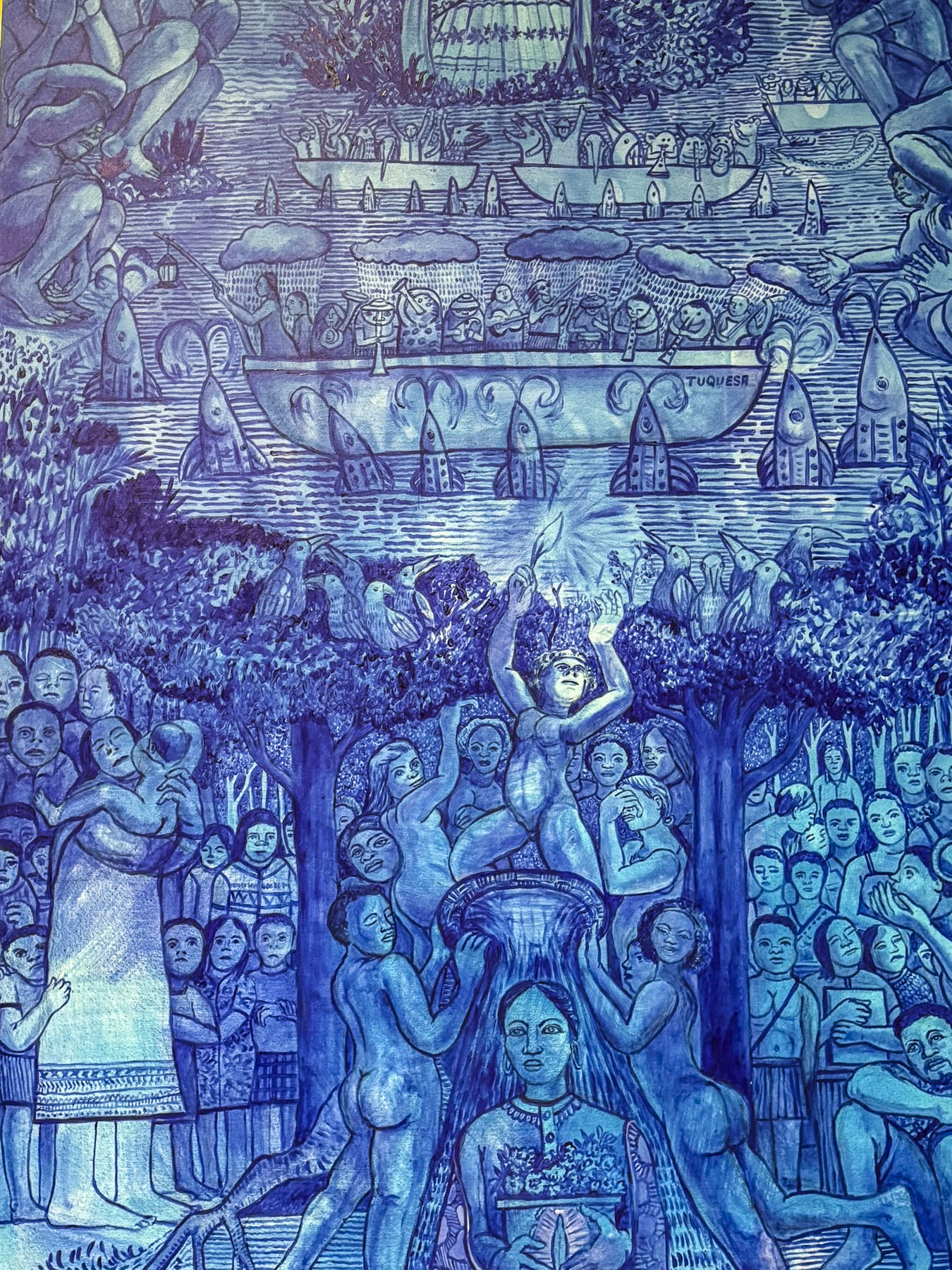

Inside the small chapel every wall and ceiling is spectacularly covered with biblical teachings. At some time over the centuries the frescoes were covered with layers of plaster and remained hidden until 1949 when the Slovenian painter and art teacher Jože Pohlen, who was born in Hrastovlje, noticed that areas of flaking plaster suggested earlier paintings underneath and thought a hidden gem might be waiting for discovery. Surprisingly, although historians don’t have an accurate history of the church, they do know thanks to the restoration of the frescoes by Pohlen, and the discovery of a signature that they were painted by Janez van Kastav, John of Kastav, from Croatia, in 1490.

All the religious illustrations were intriguing, but the most unique was the Dance of Death fresco, which depicts 11 skeletons leading a parade of everyday souls that includes a prince, a priest and a pauper to the grave. A stark reminder that, regardless of our stations in life, the same fate awaits us, though a Royal does lead the group to their final destination. Leaving the courtyard, we noticed a sign for local Isteria wines for sale on a door to one of the watchtowers. “Red or White?” “One of each, please,” and with that he unlocked the ancient wood door that was almost falling off its hinges and revealed his impromptu wine cellar.

A farmer’s enclosure across from the church had rusted relics from WWI and WW2 nailed to the top of the fenceposts. A silent and ironic testimony to the centuries of conflict that have fallen upon this bucolic area. We had hoped to stop at Lipica Stud Farm, an almost 500 hundred year old horse breeding facility that was started in 1581 with 24 broodmares and six stud horses brought from Spain originally to create a herd of the magnificent white horses for the royals of the Hapsburg Empire. Today the breeding farm remains dedicated to raising Lipizzaner horses for equestrians around the world.

Unfortunately, the equestrian center was closed the day we were in the area, and we continued on to Predjama Castle. The 13th century fortified chateau was dramatically built halfway into a large cave on a towering cliff face, by the rebellious knight Erazem, whom legend believes was Slovenia’s Robin Hood; he pillaged wealthy towns and protected the local peasants. Betrayed by a castle servant who signaled the enemy with a candle, Erazem met an unceremonious death when a cannon ball fired by troops of the Holy Roman Empire caught him with his pants down as he was using the castle privy.

An audio tour of the castle took us through secret tunnels, a dungeon, and several restored living areas, where only the lord of the castle enjoyed fireplaces, while his staff froze in their quarters. We felt the best element of the castle was its picturesque setting, which can be viewed for free, and thought that unless you have never toured a castle before, the entrance fee wasn’t worth the experience they offered. We enjoyed a very nice lunch at Gostilna Požar, which has a patio with views of the castle.

Ljubljana’s extensive old town along the Ljubljanica River is a beautiful pedestrian only area that spans both sides of the river as it flows through the capital city of Slovenia. Our taxi, on arrival and final departure, from the Parking Tivoli II lot to the French Revolution Square was included in our 5 night stay at the Barbo Palace Apartments. The short ride followed a convoluted route due to pedestrian-only and one-way streets. But it was a nice introduction to the architectural diversity of Ljubljanica, and we took note of which buildings we wanted to return to later in the week to photograph.

First, we passed the National Assembly Building of Slovenia, a modernist building with a contrasting entranceway surrounded by an immense bronze sculpture created by the work of the Ljubljanica artists Zdenko Kalin and Karel Putrih in the 1950s. The artwork is called the Working People and reflects the collective philosophy of communism and “symbolizes the progress of civilization.”

Adjacent to Park Zvezda was the beautiful, architecturally distinct hull-shaped roof and six column fascia of Ursuline Church of the Holy Trinity, a 1700s Baroque style church with an attached monastery. Across the street was the striking Pillar of the Holy Trinity.

On Mirje Street we passed the remains of the defensive wall and gates of one of Ljubljanica’s earliest settlements called Emona, a Roman colony founded in 14 AD on a pre-existing Illyrian village. Located on an important trading route that linked the Adriatic to the Danube River and the northern Balkans, the town with an estimated population of 6,000 flourished until the 5th century when Visigoths and later Huns invaded the area. Afterward the town slowly declined as folks moved away to other areas for their safety.

The short walk to the Barbo down tree-covered lanes passed the conservatory rooms of University of Ljubljana’s Academy of Music, where melodies drifted on the air, and through the recital rooms windows the heads of students intent on playing their instruments could be seen as they swayed with their music.

Around the corner from the Barbo Palace, the 18th-century residence of Count Jost Vajkard von Barbo, was a splendid view of Ljubljana Castle, across the river with its flags flickering in the wind. Our one-bedroom apartment on the fourth floor was spacious, with a small kitchen and sitting area. Though rather simple in its décor, it overlooked the interior courtyard and the ancient red tile roofs of the buildings across the way, and it was in a convenient location, the staff was quite helpful, and we enjoyed our stay.

At dusk that evening we strolled along the riverbank promenade to Tromostovje, Ljubljana’s famous Triple Bridge, the center of this historic town, which was designed by Slovenian’s famous architect Jože Plečnik (1872 – 1957). His vision transformed Ljubljana from a provincial town of the Austrian Empire into a modern European city and a regional capital within The Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the period between the two World Wars. Under his direction, while respecting the integrity of landmark buildings, the city center was reinterpreted with new bridges, promenades, streets, squares, and parks. New public buildings which uniquely combined classical and modern designs, which blended the city’s ancient Roman heritage with Slovenia’s traditional character, were added to the cityscape.

We walked variations of this route multiple times to explore this fascinating, very livable city where folks biked to work, enjoying the vibe of the university students, and the numerous restaurants and cafes in old town.

Sunlight brightening our bedroom window revealed a glorious day perfect for hiking to the top of Grajski Grič, Castle Hill. Detoured by a small antiques street fair, we browsed awhile before crossing the river to find the Reber, a narrow-cobbled path, which rises gradually until it transitions to a steep set of allegedly 115 stairs (I can’t believe they counted accurately!), before winding through the wooded hillside and reaching the castle. Along the pathway there was a spot with a nice view over the old town. The paved walkway was another initiative of Plečnik’s and replaced a dirt path that soldiers from the castle once used as a shortcut into town. Interestingly, the location is prominently featured in Vesna, a classic 1953 Slovenian romantic comedy.

Reaching the castle, we walked around its perimeter, where we watched the funicular from the central market ascend the hillside, and found some interesting historical sculptures before heading to the entrance.

The ticket booth to Ljubljana Castleis situated well in front of the castle, and you’ll need to purchase a pass if you want to visit the history museum and climb to the top of its tower. However, you can enter the courtyard of the castle for free to take advantage of a café there, and climb to the top of the ramparts which have a spectacular view of Ljubljana and the Kamnik-Savinja Alps beyond the city.

We used the funicular to descend to Ljubljana’s central market square, where in April only a few vegetable and clothing vendors were set up early in the shoulder season. Though we did find a vending machine that dispenses fresh milk into a bottle you provide or buy at the machine. Adjacent to the central market are two block long colonnaded arcades, that house several restaurants and a variety of shops. Year-round on Friday evenings the area transforms into Odprta Kuhna, the Open Kitchen Market, a popular festive hub for food connoisseurs to try traditional Slovenian dishes and international cuisines, from the numerous food stalls along the street. Unfortunately, we were not in Ljubljana on a Friday, to experience this for ourselves. But we did find some tasty burek at Okrepčevalnica Bureka short distance away on Poljanska Cesta.

We did enjoy some excellent traditional dinners in Ljubljana, the most memorable being at Ljubljančanka near Prešernov Circle, which is located the base of the Triple Bridge. The plaza is the terminus for multiple streets and is surrounded by beautiful buildings that feature a variety of interesting architectural styles.

Architectural diversity is visible on most of the lanes running through Old Town Ljubljana, and contributes significantly to the city’s livability.

One morning we walked across town to AKC Metelkova Mesto, a center of alternative culture that started in 1993 from a squat in a former military barracks. The one block area is covered in continuously evolving street art and is ground zero for nightlife in Ljubljana, with several music clubs and eateries.

Returning to the old town we crossed the Dragon Bridge, an early 1900s structure decorated with Art Nouveau dragon statues. It was not the first time we encountered dragon symbols in Slovenia. Interestingly, Ljubljana’s love of dragon imagery stems from the city’s creation story and the Greek legend of Jason and the Argonauts, in which Jason slayed a tremendous dragon terrorizing the area, after which some of the Argonauts settled along the river. Today the dragon is a prominent symbol on Ljubljana’scoat of arms, representing power, courage, and wisdom.

We found the two churches in old town interesting. Visiting first Franciscan Church of the Annunciation on Prešernov Circle, one of Ljubljana’s most recognizable landmarks, which is painted pink, a color chosen to symbolize joy and hope.

This Baroque church built in the mid-1600s replaced an earlier 13th-century Gothic church. The richly decorated interior is stunningly adorned with gilded altars, delicate stucco work, frescoes, a magnificent organ, and ornate side altars.

Across the river near the central market was the larger Saint Nicholas’ Cathedral. It is the third in a succession of churches on the site which dates from 1262 when a Romanesque style church was built. A 1361 fire severely damaged the structure and saw it refurbished in the Gothic style. But the church was altered again when the Diocese of Ljubljana was established in 1461 and the church became a cathedral. Notoriously, a suspected case of arson damaged the cathedral in 1469. Two hundred fifty years later construction of the Baroque church that exists today was started. One of the church’s most impressive features were the bronze doors created by Mirsad Begić in 1996 to celebrate Pope John Paul II’s visit to the cathedral to mark the 1250th anniversary of Christianity in Slovenia.

While Ljubljana is very easy to walk around in, the distances between points can be quite far. Helpfully, the city provides a free, on-demand electric shuttle service called Kavalir (Gentle Helper) that tourists can use in the pedestrian zone, and which is easy to arrange through your hotel. The drivers are not tour guides but will share information about the city as they whisk you quietly to your destination.

Ljubljana’s size was just right for us, its ambience charming and as a university town it was a nice mix of young and older. We found the city to be one of the nicest European capitals we have visited, and think it would be the perfect spot for an extended stay.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna

P.S. The Ljubljana Card lets you discover more than 30 Ljubljana sights