Scooters everywhere, with apocalyptic-looking masked and helmeted riders roaring along the streets, like cells in our veins always moving never stopping. Individuals off to work, parents taking kids to school, and florists delivering large floral bouquets, along with ice vendors whose towers of bagged ice tied to the backs of their scooters were slowly melting away in the heat.

Cartons of fresh eggs, ladders, toolboxes, and wheelbarrows all whizzed by our GrabTaxi, the Vietnamese equivalent to Uber, as we headed into the city. Think Mad Max set in a metropolis of ten million; Ho Chi Minh City, formerly called Saigon, was crazy!

What had we gotten ourselves into? With horrific traffic like this into the city from the airport, downtown must be a congested nightmare! But it wasn’t. The cars, buses, and scooters flowed in an impressively smooth manner during the morning rush-hour without tempers flaring or any horns being blasted.

Along our route, ubiquitous Xe Bánh Mì and Xôi, bread and sticky rice carts, were set up along the roadside curb to offer takeaway, while also offering low colorful plastic stools on the sidewalk for customers to perch on while they ate. These street vendors offered Banh mi, small French style baguettes stuffed with various fillings, or a variety of Xôi Mặn, savory sticky rice dish, traditionally served wrapped in banana leaves or a paper container nowadays.

Crossing the street was quite an adventure. We soon realized we couldn’t be timid, and followed the locals’ lead; wait for the light to change and once you commit don’t hesitate. Scooters drivers will give way; they really don’t want any pedestrians as fender ornaments.

After our long flight we spent the balance of the afternoon resting after checking into the Au Lac Legend Hotel, named for the ancient Vietnamese Kingdom. The small boutique hotel was our base for seven nights. It was conveniently located in District 3, an interesting area where “The Pearl of the Far East” remnants of Vietnam’s French colonial past merge with the vitality of a modern neon lit and towering skyline in District 1. There is a confusing merging of districts and reorganizing them into different administrative subdivisions in progress.

Later that evening we walked to Ben Nghe Street Food, a large food hall with many different stands offering a great variety of foods from seafood and Pho noodles to Bún Thịt Nướng, Vietnamese Grilled Pork & Rice Noodles. With a nightly band singing a mix of Vietnamese, and American pop songs, that included the Rolling Stones, Johnny Cash, and the Village People’s YMCA, along with its delicious food and good vibes, it’s a popular spot for locals and tourists.

After dinner we continued our first explorations of the city and headed to the Ho Chi Minh City People’s Committee building in District 1. It is a historic French colonial building constructed in 1902 that served as the Hôtel de Ville, Saigon’s city hall. Tall buildings with electronic billboards now tower over the People’s Committee Building and the in the plaza across the street there’s an imposing monument to Ho Chi Minh, the communist leader whose military campaign reunited North and South Vietnam.

On our route back to the hotel, brightly decorated street posts sponsored by BIDV, the Bank for Investment and Development of Vietnam, lit our way. Outside a college, small groups of students taking a break from their evening classes were gathered, two or three friends on a blanket along the sidewalk, thoughtfully supplied by their snack vendor.

Torrential rain and high humidity define the monsoon season that ends during late September in southern Vietnam. The streets were steaming the next morning when we peeked through the curtains of our room, but the weather report forecast clearing skies. The humidity was intense, even for two folks living in the southern United States. What we didn’t expect was the extraordinary amount of time it took for our camera lenses to defog. We observed the balletic chaos of the morning rush, which now included bicycles and an occasional xích lô, or cyclo, a traditional human-powered bicycle rickshaw where the passenger sits in a seat in front of the driver. Along with helmeted tourists and fashionably dressed women sitting side saddle as scooter passengers on GrabBikes.

Our destination for the morning was the War Remnants Museum,several blocks from our hotel, but along the way we detoured to Tao Dan Park, where morning calisthenics are a daily ritual for older folks and women who have just gotten their children off to school. The park was full of hundreds of people practicing traditional Tai Chi, aerobics, badminton, Vo Thuat Quat (fan martial arts), and Múa Kiếm (a sword dance).

In multiple sections of the park folks twisted, turned, and stretched to classical Asian music, channeled Richard Simmons with eighties pop songs, or pursued a modified course inspired by Chloe Ting, a YouTube fitness instructor. In front of the Temple of the Hung Kings, the legendary founders of the Viet dynasties more than 4,000 years ago, was a fountain with a beautiful display of orchids. Nearby the soft aroma of jasmine drifted on the air in a sculpture park.

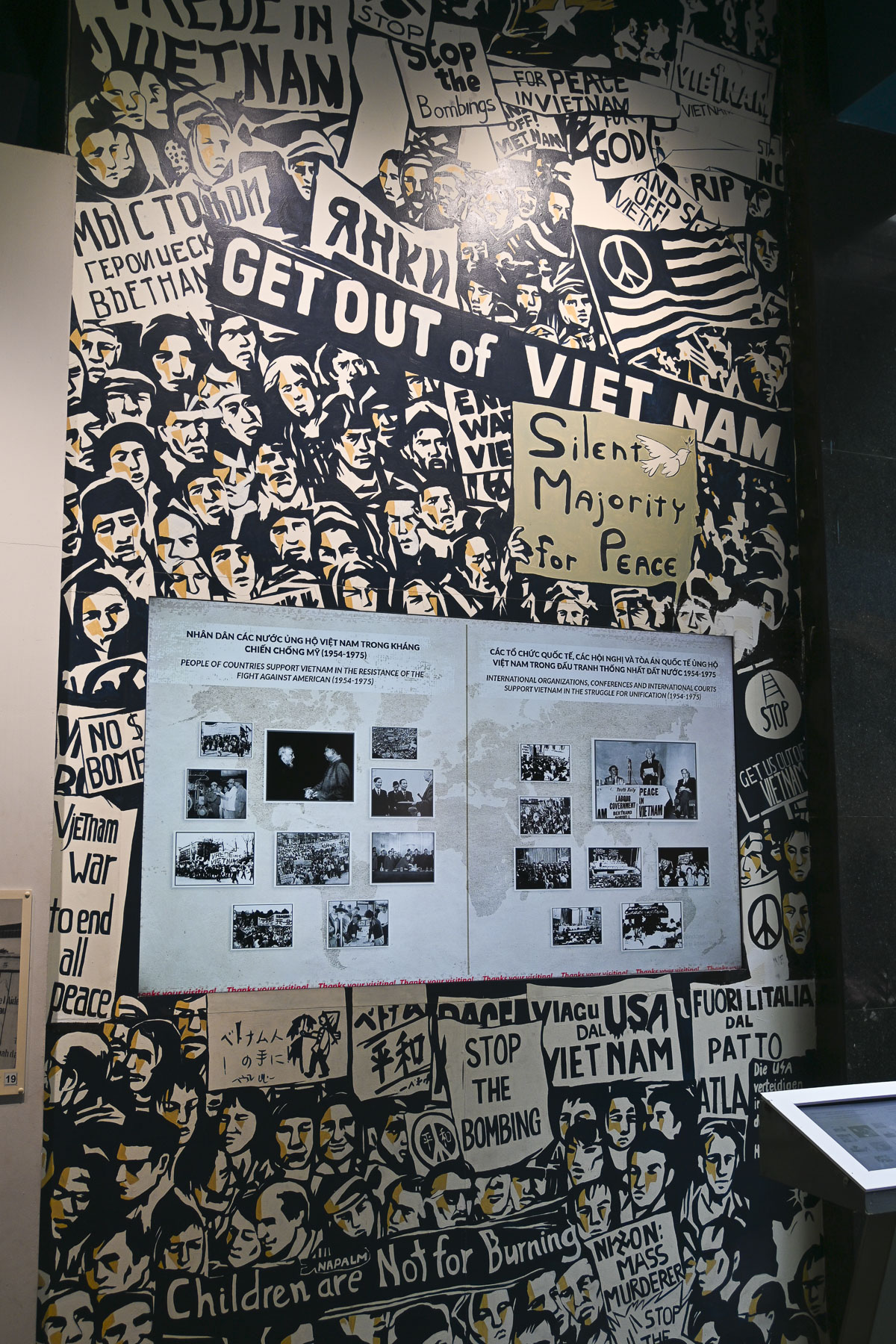

Everyday during our teen years – this certainly ages us – the Vietnam War was on the front page of every newspaper and the nightly news. We are not historians; the victors write their history and the War Remnants Museum does document both French and American participation in a horrific war. Though the museum does not address the story of the Vietnamese boat people, more than 800,000 refugees who fled Vietnam by sea between 1975 and 1995 following the war. Nor does it address the forced labor “re-education” camps spread across the country where the victorious Vietnamese communist government interned nearly one million people for three years or longer in a system of prison camps modeled after the Soviet Union’s gulags in Siberia.

Ho Chi Minh City was interesting to walk around and the next day we headed to Tân Định Parish Church, a Catholic church dating to the 1870s that’s admired for its distinctive pink façade and Gothic pillars. We then continued to Hồ Con Rùa, Turtle Lake, a large manmade lake in the center of a traffic circle. The site originally housed a water tower built in 1878, which was later replaced in 1921 with a statue of three French soldiers around a water fountain, symbolizing their colonial rule over Vietnam. This monument lasted until the French army left Vietnam in 1956. The lake was later enlarged in 1967, and the concrete tower that looks like a blooming flower was added by the newly elected president Nguyen Van Thieu of the Republic of Vietnam.

There’s a legend associated with the tower – it says that the president, to ensure his success, “invited a famous Chinese feng shui master to assess the land at Independence Palace,” now Reunification Convention Hall. The feng shui master praised the palace for being built on a dragon’s head, but the dragon’s tail was wildly thrashing about in Turtle Lake. In feng shui terms, this was really bad news for political stability, and a large turtle needed to be cast to hold down the dragon’s tail. Following the master’s advice a turtle sculpture was cast and placed at the center of walkways built over the lake that resemble a bagua, a feng shui symbol used for protection. And the flower shaped tower was reinterpreted as the shaft of an arrow shot into the tail of the dragon to pin it down. The turtle didn’t survive the city’s new communist regime and was destroyed in 1976. The plaza, surrounded by a variety of restaurants and coffee shops, was a nice place to relax for a while.

There are many upscale stores and shops across the city, but for every fancy store there are multiple small mom and pop shops that specialize in one item, like glassware or wicker, which is spilled onto the sidewalk in order to show the wares. There were numerous small mechanic shops that tended to the thousands of scooters that whizz around the city; they conducted their business on the sidewalks, repairing tires, changing oil, rebuilding engines, or doing body work and spray painting. This sidewalk sprawl often forced us to walk in the street to pass by.

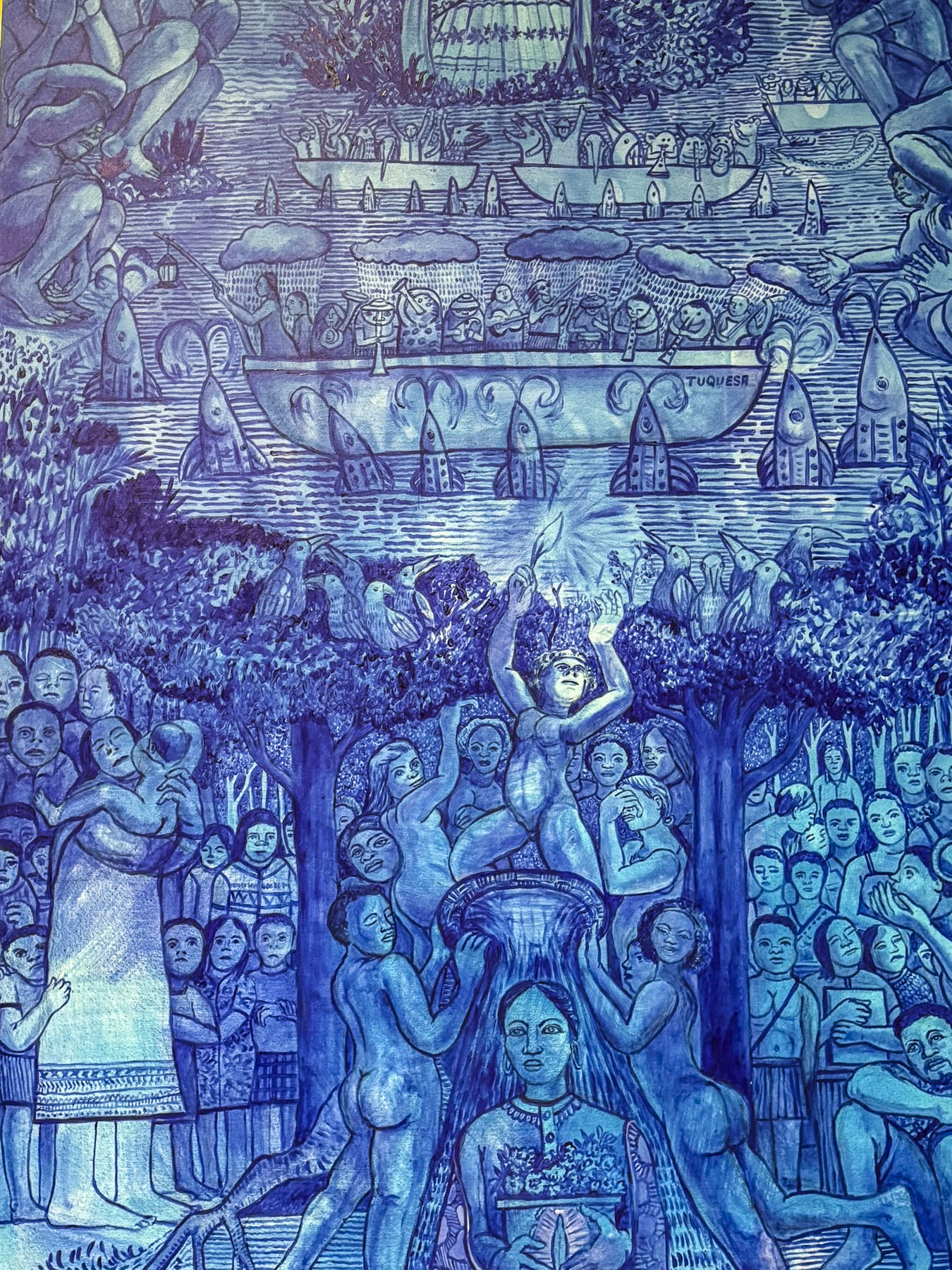

A large metal relief sculpture above the entrance to the Ho Chi Minh City Museum of History caught our eye as we headed to the Saigon Zoo and Botanical Garden in District 1. The cataclysmic scene commemorates the great victory of Vietnamese General Trần Hưng Đạo over the army of the invading Mongol Empire in 1288. The captioning on its placard described it as “emphasizing national heroism and successful resistance against foreign invasion, a recurring theme in Vietnamese history.”

Founded by the French in 1864, the zoo is the eighth oldest in the world and a beloved destination for generations of Vietnamese families. The botanical section with its topiary sculptures of wild animals is what drew us here and we spent about two hours wandering the gardens amid flowering plants, a collection of bonsai trees, some irresistible reptiles, and a miniature Jurassic Park geared for kids.

Turning left upon exiting the zoo we were waiting for a traffic light to change at the intersection of Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh, when we noticed a row of recently painted patriotic street murals. Obviously, these were government approved to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War and the thriving economy that Vietnam now enjoys. Graffiti is unheard of and unapproved street art as a form of expression is illegal throughout the city, and the few decorative murals on buildings we saw were apolitical but still required the city’s permission. While talking about the unusual, we also didn’t see any homeless people sleeping rough on the streets. This is due to active government policies that relocate homeless individuals to social support centers, their home region, or shanty towns away from the city center.

Walking back towards the historic center of District 1 we passed tall glass office buildings and transportation infrastructure projects built to sustain one of the fastest-growing economies in Southeast Asia, which is transforming Ho Chi Minh City into a global financial hub by focusing on digital technologies, finance, and high-tech industries.

Near a plaza along the Sông Sài Gòn riverfront with a statue of the legendary General Tran Hung Dao we ducked into a passageway, off Mạc Thị Bưởi, lined with artwork called Alley 39 that opened to a narrow lane lined with small no-frills restaurants filled with folks. We found one with an empty table and enjoyed Pho for lunch.

Afterwards we headed to the Municipal Theatre of Ho Chi Minh City, Saigon’s old opera house built by the French in 1897. It’s a fine example of grand colonial architecture, and it served as the legislative assembly for South Vietnam after the war before being restored to its original use and declared a national monument in 2012. Surrounding the opera house are several small squares with musical themed statuary. It’s also a popular place for couples to have their engagement and wedding photos taken and there even seemed to be two vintage sports cars permanently parked there to facilitate a variety of shots.

It was a long hot and humid day, but we strolled slowly back to our hotel past Saigon’s monumental Central Post Office. Across from it was the Notre Dame Cathedral of Saigon, wrapped in construction scaffolding for a multi-year renovation. It was extravagantly constructed between 1863 and 1880 with every brick, piece of structural steel, nail and stained glass window imported from France. Both structures are beloved vestiges of the city’s colonial past and historic landmarks. While Vietnam’s communist government officially guarantees religious freedom in its constitution, it heavily regulates Buddhist, Catholic, Protestant, and Islamic houses of worship and the activities they support via the Government Committee for Religious Affairs.

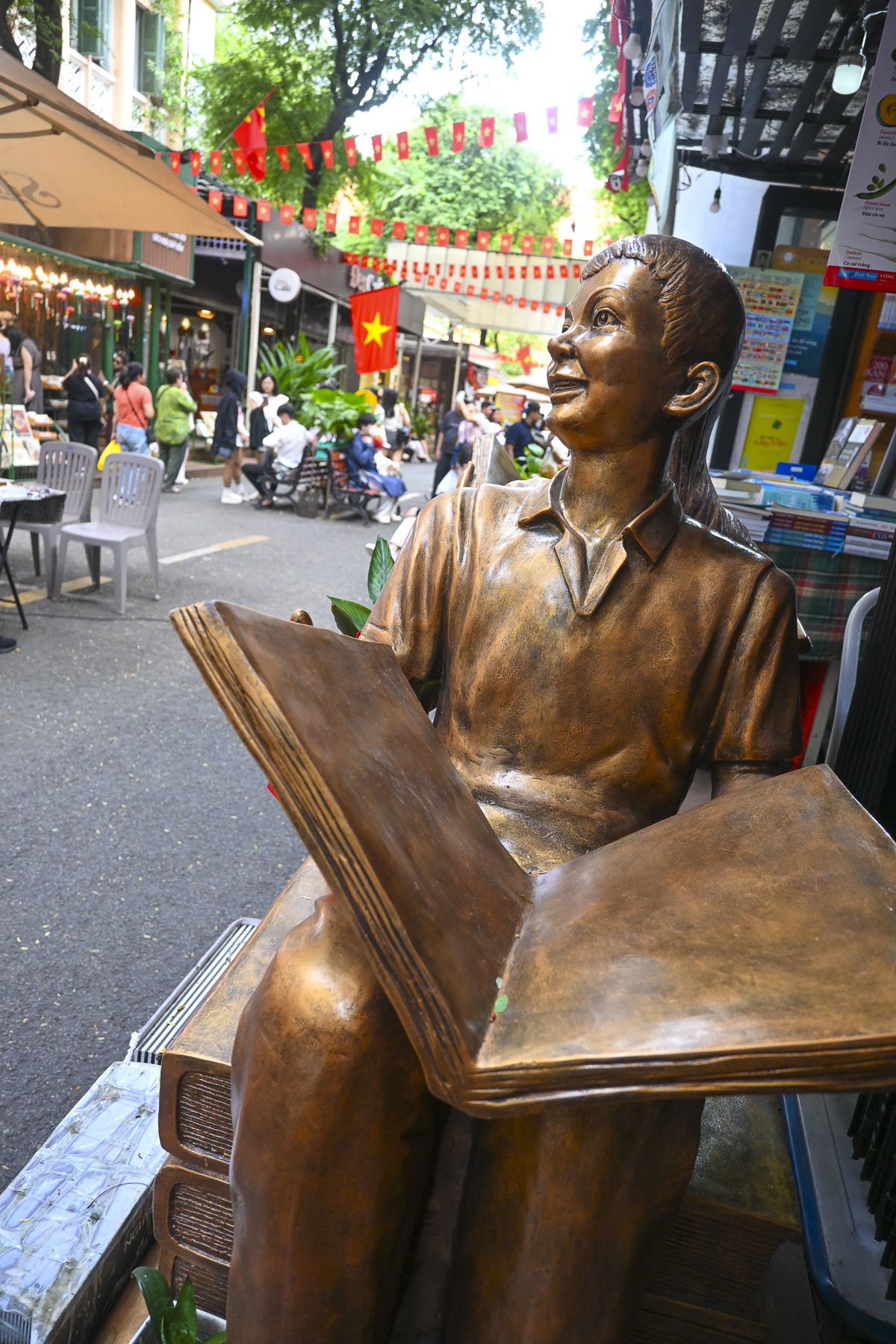

Next to the post office was Nguyen Van Binh Book Street, a pedestrian-only lane lined with books, shops, and cafes. As we enjoyed a cup of coffee in a café, the bookseller across the way sent her young daughter over chat with us, to practice her English. The young girl spoke very well, and we enjoyed her company, but she soon lost interest and wandered off.

The next day we hired a private driver, a relative of the hotel’s concierge, to take us to the town of Thủ Dầu Một to see the reclining Buddha at the Hoi Khanh Pagoda complex, and several smaller temples on the return trip to the city. This was a fascinating ride down roads filled with overburdened scooters delivering various wares and lined with weathered roadside businesses that included a rubber clogs shop and factory with thousands of brightly colored shoes, a coffin shop, poultry and gold fish stores, a birdcage shop, various statuary makers, one of which had a Statue of Liberty out front, and numerous mechanic shops. It’s traditional for business owners to live above their tightly spaced shops in narrow dwellings called “tube homes,” which are often faced with marble to reflect the prosperity of the owners.

The massive pure white Buddha is 52m (170ft) long and reclines atop the temple’s two-story Buddhist academy. Along the base of the giant statue are 20 reliefs showing the life of the Buddha from his birth to his Parinirvana. According to the Buddhist tradition, women cannot ascend to the status of a Buddha — one who is awake, enlightened and emancipated. I like to tease Donna, who is a Methodist minister, that she might have been a little too close for the Buddha’s comfort, and he pushed her as she was coming down the stairs. Fortunately, a very sweet vendor selling flowers for offerings gave Donna an herbal salve to help with the immediate pain while our driver hurried down the street and bought two bags of ice from a nearby restaurant, to help reduce the swelling.

Across the street was the site of the original small Hoi Khanh temple, first established in 1741 by Zen Master Đại Ngạn Từ Tấn, a third-generation monk. This temple was destroyed during fighting in 1861, as the French colonial army colonized southern Vietnam. The temple is a major spiritual site in the region and continuous to evolve with additions of the seven-story pagoda in 2007, along with the academy and reclining Buddha in 2010.

Returning to Ho Chi Minh City, we visited the Vinh Nghiem Buddhist Temple in District 3, where we incorrectly assumed that classical design of the temple reflected its ancient history, only to learn that the temple complex was started in 1964 by two monks who migrated from North Vietnam to spread the Truc Lam Zen meditation sect to the south of the country. The Vinh Nghiem Pagoda holds an important role in the spiritual life of Ho Chi Minh City. “It serves not only as a place of worship but also as a center for moral education and community learning. The temple actively promotes Buddhist teachings on compassion, mindfulness, and filial piety through lectures, study courses, and social activities.” It’s a large complex with many areas and a 14m (46ft) tall stone memorial tower, that was once the tallest in Vietnam. In the Buddha Hall we received our first introduction to Buddha puja, a devotional tradition that symbolizes respect to Buddha by offering fruits, clean water, non-alcoholic drinks, or vegetarian foods. These offerings are often shared daily with the less fortunate.

The Saigon Cao Dai Temple in District 5 was the last temple we visited and fascinatingly different, with a tarpaulin covered courtyard sheltering scooters, coffins and a hearse. Cao Dai was formally established in 1926 in southern Vietnam by Ngô Văn Chiêu, a civil servant who received divine revelations, along with several others who practiced spiritualism, to create a syncretic religion that unites the philosophies of Buddhism, Confucianism, Hinduism, Catholicism, Protestantism, Judaism, and Islam into a into a single, universal faith.

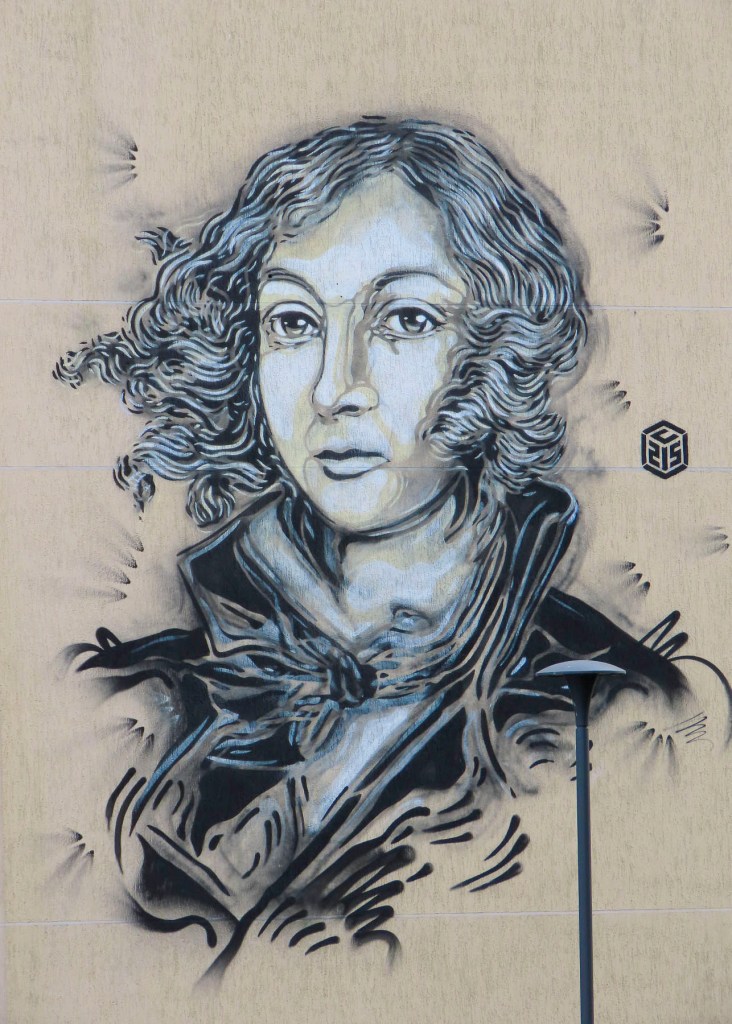

The group revealed through séances the faith’s three saints and “Divine Messengers;” French writer Victor Hugo; Sun Yat-sen, a Chinese revolutionary who fought against oppressive rule; and Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm, a 16th century poet regarded as the “Vietnamese Nostradamus” for his accurate prophecies. The faith’s minor saints include Joan of Arc, Thomas Jefferson, William Shakespeare and Louis Pasteur, amongst others. In the sanctuary colorful dragon motifs surrounded an altar prominently displaying the Eye of Providence.

On our last day in the city we waited for morning showers to clear before we took a GrabTaxi to Landmark 81. With eighty-one floors, this has been Vietnam’s tallest skyscraper since its completion in 2018, a symbol of Vietnam’s economic growth, and an iconic structure on the city’s quickly evolving skyline. It’s a mixed use building with a shopping mall and entertainment complex, residential apartments, and the Vinpearl Landmark 81 – Autograph Collection hotel. We, however, were there for the fantastic panoramas of Ho Chi Minh City’s sprawling metropolis from its SkyView observation deck.

Afterwards we took another GrabTaxi to Ben Thanh, the city’s old central market in district 1, where a bazaar has been on this site since the 1600s. The current building dates from the French in 1914. It’s a sprawling place with hundreds of stalls offering clothing, food and everything in between. The premium outer perimeter stalls are operated by the government with set pricing, while the maze of hundreds of inner stalls offer dynamic opportunities to bargain. We bought several shirts and blouses, along with some dresses for our granddaughters at very reasonable prices. Nearby was the nicest fish store we’ve ever visited. It featured a towering pyramid of sculptural water tanks holding the fresh catch of the day.

After returning to the hotel for a reprieve from the day’s heat and humidity, we headed out in the early evening to Bui Vien Walking Street, the city’s center for nightlife. It’s known for its partying atmosphere along a vibrant neon-lit street lined with open-air kitchens, bars and clubs that stay open into the early hours of the mornings. It was a fun place to stroll, and people watch as the night sky darkened and more groups filled the street.

We are not sure why it took us so many years to get to Southeast Asia, and Vietnam in particular. It was a nice change from our European centric vacations, and we found Ho Chi Minh City to be a youthful, vibrant and energetic destination that was very affordable compared to the United States and Europe. Everyone we encountered was friendly and welcoming, with the hotel staff almost feeling like family by the time we left. And we managed to stay dry during the occasional monsoon downpour with the help of umbrellas provided by our hotel.

Since the airfare is a considerable portion of any trip, we also booked a cruise up the Mekong River to Cambodia because we’re not sure if we’ll get a chance to return one day or decide to explore other areas of Asia. But after getting our feet wet in Vietnam, we are confident we’ll enjoy wherever we choose to go next in the region.

Book your flights!

Till next time,

Craig & Donna