By the time we picked up our rental car at the Tocumen International Airport it was the height of the evening rush hour in Panama City. Fortunately, we were heading into the city, while the traffic lanes carrying the daily exodus of commuters home from the financial capital of Latin America were jammed. It was only a twenty-five minute drive to our hotel on the waterfront, but we missed our exit and had to re-route our way through the now deserted downtown streets to the Hotel Plaza Paitilla Inn, for a one night stay. We chose this 19-floor waterfront hotel after determining it was the best place to get those iconic photographs of the city’s modern skyline along the Pacific Ocean coast. And we were not dissappointed.

Golden light filled the room as we drew back the curtains along a wall of windows to reveal a spectacular cityscape that transitioned through the sunset, twilight, and darkness. It was a million-dollar view and we felt as if we were some place only accessible to billionaires or actors lucky enough to have a movie scene filmed on location here. Surprisingly, the Hotel Plaza Paitilla Inn was an excellent value and very budget friendly.

After discussing our travel plan with the concierge the night before, we departed after an early breakfast to avoid the expected traffic delays as folks took the Friday afternoon off in anticipation of the four days of Carnaval before Ash Wednesday. The nationwide el Carnaval de Panama, which literally happens in every town, is the biggest celebration of the year in the country. It starts in each town with the coronation of a queen and ends with the Burial of the Sardine, which symbolizes the past festivals and enjoyment of drink and food, in the predawn hours of Ash Wednesday, and the beginning of Lent. Little did we know that Panama’s Carnaval is regarded as “one of the largest— and rowdiest — events in Latin America.” Nightly events feature themed parades with elaborately decorated floats escorted by trumpet and drum bands, called tunas. To the benefit of all, water trucks called Culecos spray the revelers in the ninety-degree heat to keep them cool. And between the water trucks, mojaderas, wetters, keep everyone partying around them soaked with water pistols, water balloons, and buckets of water. It’s not a particularly camera-friendly event.

Our destination for the next 5 nights was Posada Los Destiladeros on Playa Los Destiladeros, in Los Santos Province, a 5 hour, 335km (208mi) drive. Leaving the city, we crossed the Bridge of the Americas which soars 64m (210ft) above the Panama Canal, and stopped on the far side at the Mirador de las Américas for our first look at the canal. Two monuments commemorate the arrival of 750 immigrants from China 170 years ago to work on projects relating to the construction of the canal, which created an enduring friendship between Panama and China. The view of the canal wasn’t as impressive as its fact sheet: over 12,000 ships carrying $270 billion worth of cargo pass through the locks of the canal annually. Over 70% of the ships are headed to or are returning from ports in the United States.

Continuing on Rt1 we passed the first of many pillars being constructed to support Panama City’s new Metro 3 line, a double-track monorail project sponsored by the Chinese, that will connect the growing towns of Ciudad Del Futuro and La Chorrea to the city’s Metro 1 and Metro 2 lines, Central America’s first and only subway system that became operational in 2014. Rt1 is alternately called the Pan-American Highway, that famously stretches from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska in the United States, 19,000 miles way to Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego in Argentina. Though a 100-mile section is missing in the difficult terrain of treacherous Darien Gap region between Yaviza, Panama and Chigorodó, Colombia.

Shopping centers and strip malls with McDonald’s golden arches, Starbucks, and Burger Kings lined both sides of the highway before giving way to open crop- and pastureland. The occasional hilltop offered views of the Gulf of Panama and the Pacific Ocean to the south. While to the north the rural highlands of the Cordillera Central, the jagged mountainous spine of the country, graced the horizon. Veering off the Pan-American Highway we headed west on Rt2 to Las Tablas. The town has been ground zero for Carnaval in Panama since the mid-1800s when two fiercely rival groups representing Calle Arriba and Calle Abajo started to compete in a festive, one upmanship every year before the 40 days of Lent began. The event in Las Tablas is very popular with folks from Panama City seeking to experience a more traditional Carnaval with folkloric music and regional dress, in what many consider Panama’s “heartland.”

Traffic had been slowly building all morning, and by early afternoon the streets of our intended route were blocked with floats being prepared for the weekend’s first parade that night. Folks were already creatively parking along the side of the roads and walking to the town’s central plaza, Belisario Porras. The congestion in the town unfortunately nixed our plans for lunch there, and we continued on for several miles along Rt2 through a scenic landscape of lightly treed hillocks. Cattle grazed in the shade under the trees.

Cars were parked on both sides of the road in front of El Cruce #2. It was a small fonda – a Panamanian roadside food stand, with smoke billowing up from its barbeque pit. It piqued our interests, and we stopped. The outside grill area was open sided, under a corrugated tin roof. In its shade a man prepped and attended the meats that were smoking above a fire while another was using a machete to shave kernels from ears of corn. The unhusked pile next to him seemed monumental, akin to the Greek myth of Sisyphus and his never-ending task. It was the beginning step in the preparation of masa, a corn flour. It’s a must-have ingredient for traditional, homemade corn tortillas and tamales. The menu hung above a small window to the kitchen filled with women attending various stoves. Everyone was very nice and curious about where we were from, but seemed surprised that we had stopped. A large John Deere combine harvester with a police escort passed as we ate. A small caravan of pickup trucks with farm workers standing in the back followed it slowly down the road. The fonda was a very authentic, nothing touristy about it experience, and the food was good. The line of traffic behind the harvester slowly disappeared as cars passed it when the opportunity arose. It wasn’t until the last seconds as we raced past the tractor that we realized we also had to pass the police car! We returned the officer’s wave. It seemed like it was an everyday occurrence in the rural countryside. In Pedasi, the closest town to our hotel, preparations for the Carnaval were also visible down the side streets.

We missed the entrance to the hotel and continued down the road in hope of finding an easy spot to turn around, only to find that the road suddenly ended, with a log across it, at the top of Playa Destiladeros, a short distance away from the thundering waves of the Pacific Ocean, as if an early extension had been washed away in a storm. We were at one of the farthest points south on the remote Azuero Peninsula.

When we made plans for this return layover from our trip earlier in the month to Uruguay and Argentina, we didn’t realize our week coincided with Carnaval, consequently many of the hotels we were interested in were fully booked. After scouring the map for areas we wanted to stay we found Posada Los Destiladeros. While it showed as fully booked on Booking.com and Hotels.com, we were able to book a room directly through the hotel’s reservation page.

From the gated entrance we followed a long twin-tracked road, through a large palm tree covered property with many outbuildings, to the parking area. Through a grove of palm trees, the inviting blue water of the Pacific glistened behind the receptionist.

The vibe was really nice. It’s an unpretentious, tenderly time-worn resort in a verdant oasis of greenery on the low cliffs overlooking a wild beach and undeveloped coastline. The staff were very nice and friendly, and after a few days felt like family. The dinners that emerged from their kitchen were extraordinary!

It’s very unusual that we stay in one spot for 5 nights to unwind. But the Posada Los Destiladeros was the perfect place for us to relax, with easy walks on the beach, lounging around the pool and under palm thatched gazebos overlooking the surf as we waited for sunset every day, which offered a dramatic play of light across sand and surf.

A conversation in the pool one afternoon with another guest, a Panamanian American man visiting family over the week of Carnaval, related that he and his wife had been coming here for years, but “somehow it remains a hidden gem.” Of course, we took several half day trips to explore what else the Azuero Peninsula had hidden away.

Several days later we drove toward the beach town of Las Escobas del Venado. Well suited to the heat and humidity of the region, herds of Brahma cows have rested in the shade of the region since Spanish colonists first brought them to the area in the mid-1500s. At a turnoff for the small ranching town of Los Asientos, a roadside monument highlights the town’s traditional la corridas, bullfights. These are non-lethal events since a 2012 law prohibited the injury or death of the bull; however, la corridas are still popular in rural Panama. Along the road milk cans were placed next to the rancher’s gate, waiting for the local dairy cooperative to pick them.

A little way farther along, the colors of the tombs in a small cemetery seemed to vibrate against the verdant landscape, which receives between 45 and 90 inches of rain every year. A large group of cyclists, followed slowly by a support vehicle, made passing difficult along the narrow hilly road, with many blind curves. Though the congestión they created was well tolerated, without the honking of horns. Drivers respected their safety and gave them a wide berth when they were eventually able to pass. Small artesanal lumber mills along the way vertically stacked their milled lumber, like skis, against a wall to dry.

During the dryer summer months the Rio Oria lazily flows through the ranchlands to the ocean.

Las Escobas del Venado was the closest example of a traditional beach town, with several small hotels build along the shore of the half-moon shaped Playa Venao. It is not by any means a large resort town. The beach is very wide and shallow, especially when the tide is out, and it’s a popular spot to horseback ride or drive an ATV along the sand. Across the water a sailboat was safely anchored out of the wind and rolling waves behind the bluff at the southern end of the bay. The day was very hot, so we didn’t spend much time on the beach, and hugged the shade as we walked to the Almendro Café for our traditional “walk a little then café.”

It was a really nice spot, under large shade trees. Our coffees and pastries were excellent, and its menu looked very good with vegetarian, vegan, and gluten-free choices. It was to our surprise part of the Selina River Hostel which promotes itself as a destination for digital nomads to enjoy the sun, surf, and sand of Playa Venao. We definitely skewed their demographics for the morning.

We continued driving into the highlands along Via Hacia El Carate, a narrow serpentine road that rose through a mesmerizing landscape of hills and valleys. Unfortunately, there were not any places to stop along the way until we reached the Mirador La Vigía, which offered great views of forested ranchlands, backed by the Pacific Ocean on the horizon.

Familiar with the road now, we occasionally stopped along gated pastures to photograph the expansive landscape, that showed little sign of human intrusion, as we followed the same road back downhill.

They were few opportunities for lunch along the way so we decided to head back to the Almendro Café at the Selina River Hostel . We were not disappointed; the food was excellent and healthy. It’s so nice to order from a menu that doesn’t automatically serve French fries with every order.

Nearing our hotel, a rancher blocked the road with his herd of cows as he moved them to a different pasture.

We were back in time to watch the sunset over Playa Destiladeros. We stayed until the last color in the sky had faded away before walking back to the resort’s restaurant, where we usually dined inside to take advantage of the air conditioning and ceiling fans.

Though having breakfast on the veranda, with the sound of the waves crashing in the distance, was a delight during the cool morning hours.

Early morning walks along the beach as the sun crested to the horizon were equally as enjoyable as the sunsets, but more tranquil with squadrons of pelicans swooping low over the surf, looking for fish. Occasionally some would peel away to dive headfirst into the water to catch fish.

Remnants of Carnaval celebrations the night before were still visible in the small towns along our route as we headed back early to Panama City to avoid the traffic. We arrived on the outskirts of the city sooner than expected and decided to spend the afternoon at Perico Island. Located at the end of the very long Amador Causeway which extends for 6km (3.7mi) into Panama Bay, it’s a popular spot for city folks to catch the breezes, picnic, rent bicycles or walk along its full length which offers great panoramic views of the city’s modern skyline and large cargo ships underway to the entrance of the Panama Canal.

After strolling along the waterfront for a while we decided to have lunch at Sabroso Panamá, a uniquely decorated place with a nice vibe, that also had a balcony overlooking a marina. We tried the carimañolas, similar to empanadas, though they are made with mashed cassava (yucca) dough and then fried.

Carnaval celebrations continued that evening and the direct route back to Hotel Plaza Paitilla Inn (we had such a nice experience there earlier in the week we decided to stay there again) along the Cinta Costera, the city’s waterfront park, and the eight lanes of the Pan-American that parallel it were blocked, and we had to circumnavigate our way around it. The massive street party continued well past midnight into the wee hours of Ash Wednesday morning.

Ash Wednesday was our last full day in Panama City, and we spent it exploring the Casco Antiguo, the historic old town district which dates from 1673, and is also known as Casco Viejo or San Felipe.

This town, built on a defensible small peninsula, replaced the city’s original settlement, Panama La Vieja, which was started 11km (7mi) farther east in 1519 when Spanish conquistador Pedro Arias Dávila landed 100 settlers along the coast, and built the first permanent European settlement on the Pacific. The city prospered for 150 years as the Spanish used the town as a base for expeditions to conquer the Inca Empire and sent the plundered gold and silver they seized back to Spain. The city’s wealth did not go unnoticed, and in 1671 the British privateer Henry Morgan landed over a thousand brigands on the Caribbean coast and trekked through treacherous jungles across the Isthmus of Panama to reach the city, which they then attacked, pillaged and burnt to the ground. Six hundred Spaniards died during the assault. Though the booty they looted wasn’t as much as expected, Morgan was declared a British hero, and knighted.

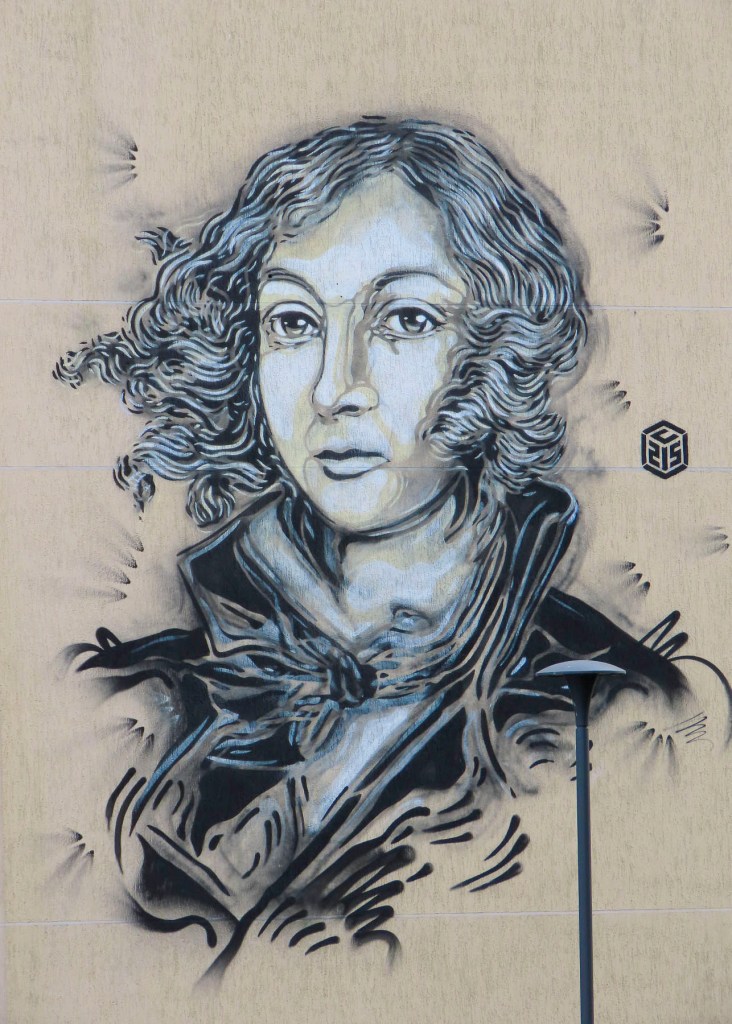

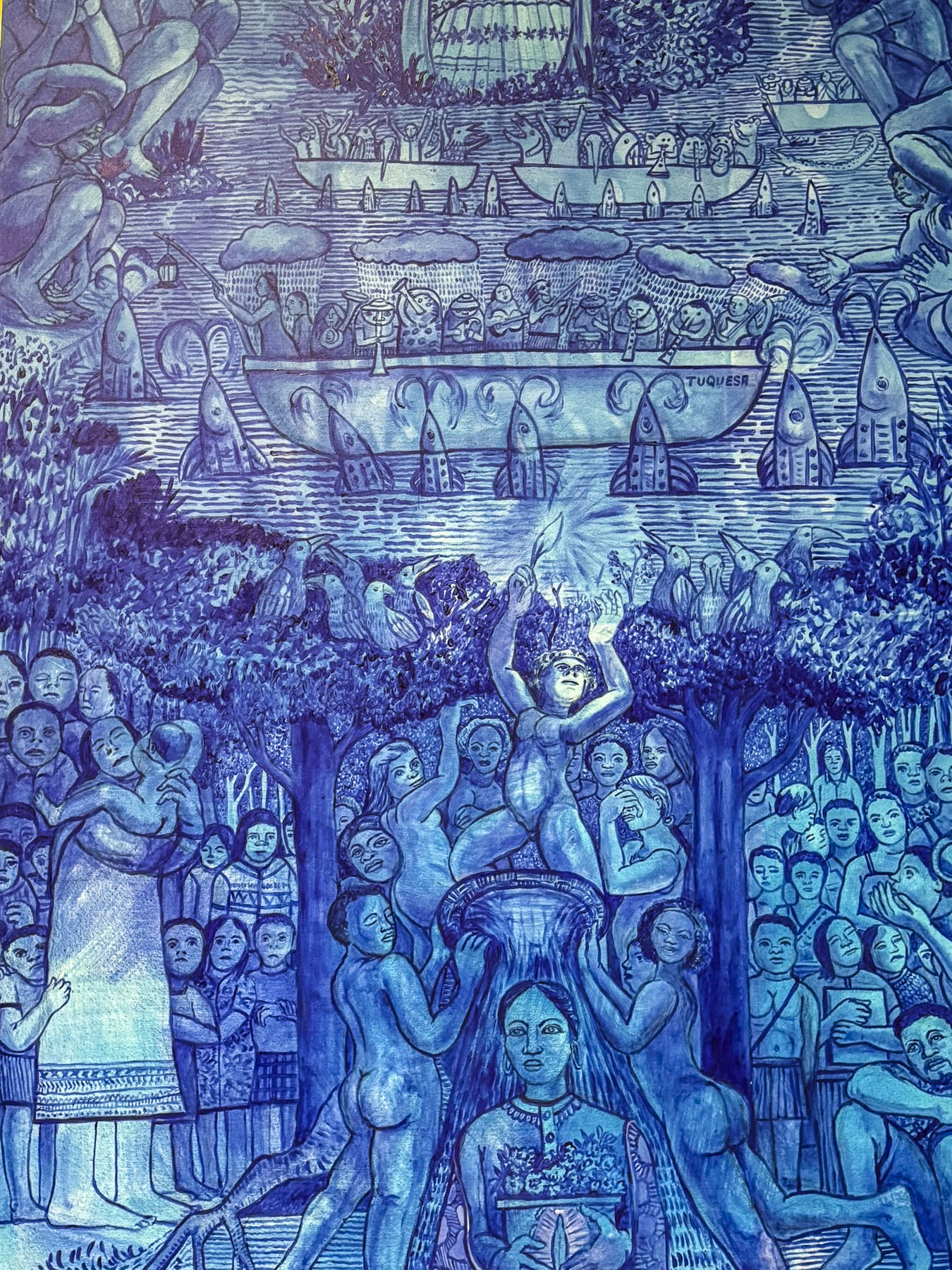

We arrived by Uber to the Catedral Basílica Metropolitana Santa María La Antigua on the Plaza de la Independencia in the center of Casco Antiguo. Its striking façade which blends Baroque and Neoclassical architecture dates from 1688, but the cathedral took more than 100 years to build, and wasn’t consecrated until 1796. Inside, an interesting mural in monochrome blue depicted the indigenous peoples of Panama accepting Chrisitanity.

The Old Town was once a citadel, though the defensive wall which encircled its 36 blocks was taken down ages ago to ease its expansion. Surprisingly, within this small area there were 4 still active historic churches and the ruins of another. Our basic plan was to visit every church and then spur off to other nearby points of interest.

Adjacent to the cathedral was the Museum of Panamanian History, housed in the Municipal Palace of Panama. It’s a beautiful Neo-Renaissance style building with pilasters, arches and decorative cornices. We didn’t tour the exhibits, but we did enjoy resting in the air-conditioning of the lobby.

The narrow-bricked lanes were more suitable for the horse drawn carriages for which they were designed than the cars of today. They surrounded a plaza full of colorful well-maintained 18th and 19th century buildings with decorative iron railed balconies covered by profusely blooming bougainvillea.

Cafes surround the Plaza Simón Bolívar where a grand monument commemorates the Latin America independence hero. Behind it the graceful belltower of the Saint Francis of Assisi Church looms above the plaza. It was a later addition to the original early 1700s church that was damaged during fires in 1737 and 1756.

Nice views of the modern Panama City skyline were available along the lane leading to the Corredor Artesanal De Casco Antiguo, a trellis-covered lane with flowering vines that offers shade for the indigenous artisans who have stalls along its length.

Back in the center we passed the ruins of the Iglesia de la Compañía de Jesús. It was built as a Jesuit monastery in 1641 and later in the 1740s it also served as the home of the Royal Pontifical University of San Javier, Panama’s first university, until the Spanish Crown banished the Jesuits from the colonies in 1767, and the church and monastery was abandoned. The ruins still standing are all that were left from a 1781 fire that ravaged the complex.

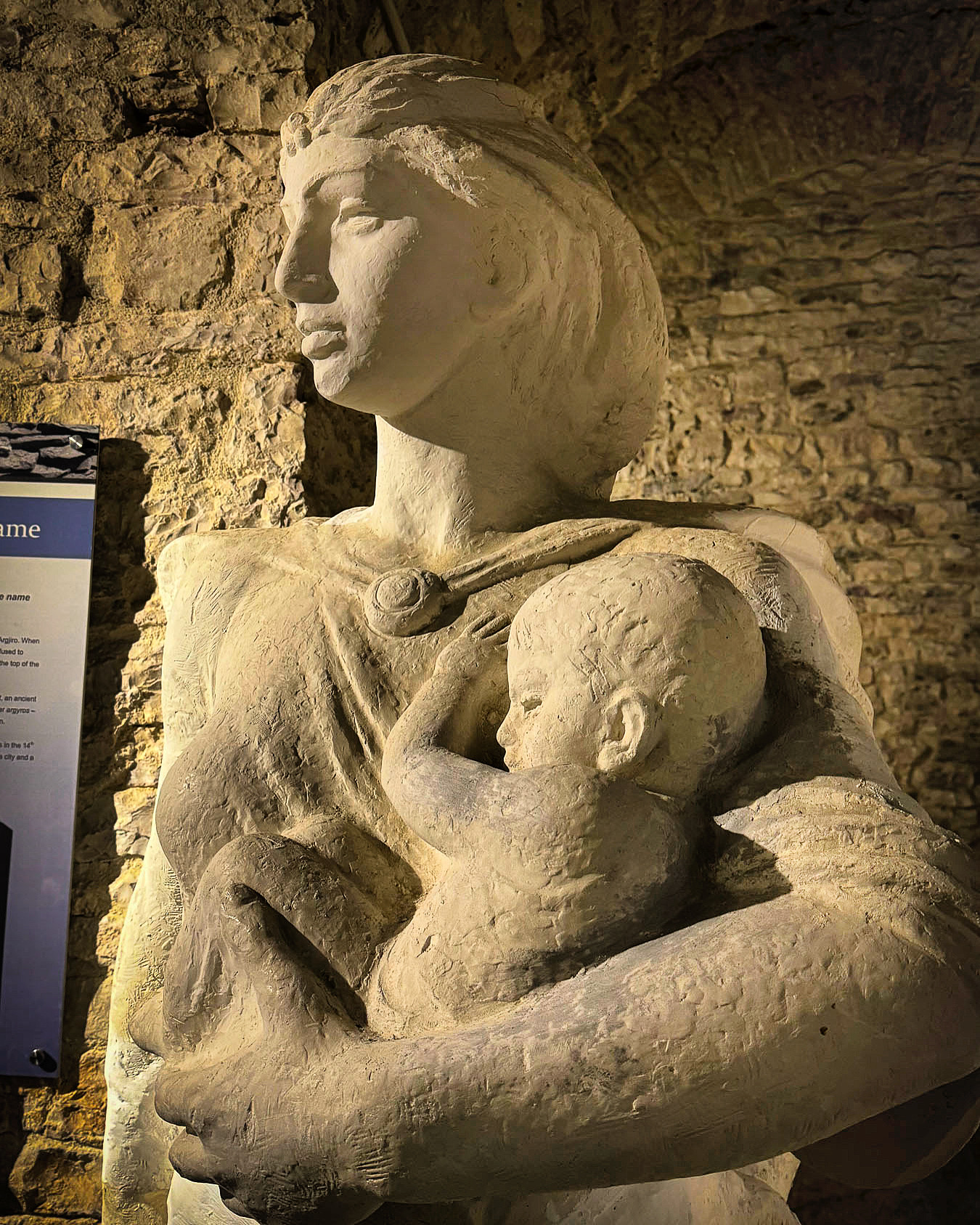

A block away was the Iglesia de San José. The 1670s church is notable for its ornate gold altar, that legend believes was saved from Morgan’s pirates by a priest who painted it black to hide its importance. There is also an interesting collection of religious sculptures and nativity scenes in a side chamber.

Afterwards we headed to the Santa Anna neighborhood, which was outside the walled citadel. While parts of it are in the UNESCO protected area of the Casco Antiguo; most of it is not. We had read that the area has great potential with many older buildings needing renovation, but were surprised by the quick transition from one neighborhood to another. While hopes are high for the barrio, many of the buildings we passed were only colorfully painted facades, with the sky above showing through the windows of roofless buildings.

Returning to Old Town we passed the Iglesia de la Merced, the only church to survive, fully intact, the destruction of Panama La Vieja during the pirate’s 1671 attack on the town. After the attack the church was disassembled by Franciscan monks and moved stone by stone to the new town, where it was painstakingly rebuilt, and is believed to be several years older than Iglesia de San José.

Our “walk a little then café,” beckoned when we happened upon Café Unido, a local coffee shop that pridefully specializes in Panamanian grown coffee, which they consider the best in the world.

A delightfully warm March day wandering the colorful streets of the Casco Antiguo was the perfect way to end our week in Panama. Between the beauty of the countryside and the coast, along with the warm hospitality of the Panamanians, we can understand why the country is a warm weather haven for expats from all across the northern hemisphere.

Hopefully, we will get the opportunity to explore more of the country in the future.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna