A row of windmills silhouetted against the early autumn twilight lined the road as we sped toward Kuressaare, the largest town on Saaremaa Island. A heavy plumbeous cloud cover was darkening the sky earlier than usual, but we hoped to reach our lodging, Vinoteegi Residents, before nightfall.

From past experiences of driving in Europe, parking our rental car was always an issue, and sometimes very costly. We were pleasantly relieved during our three-week road trip through Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania that we only had to pay for parking once when staying in Riga, Latvia. The rest of the time, convenient and safe parking was available on the street. After settling into the charming boutique hotel, we walked several blocks through a residential area and the historic town center to dinner.

On the town square the lively activity at Söstar köök & baar caught our attention, and we enjoyed several tasty selections from their eclectic menu.

The next morning, we were up early to take advantage of the photographer’s “golden hour,” at Kuressaare Castle, a twenty-minute walk from our hotel. Our stroll down the quiet neighborhood lanes was a nice introduction to the town’s charming diverse architecture.

In the dawn light the bastion fortress, Saaremaa Island’s most iconic landmark, looked particularly beautiful and intriguing. So much so that we found ourselves returning to the citadel several times during our stay to snap photos of it in different light.

Construction of the fortress’s earthen ramparts started after the Teutonic Order defeated the pagan Saaremaa islanders during the Great Northern Crusade in the early 1200s. A century later the fortress was transferred to the Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek, based on the mainland in Haapsalu, and the building of the three story, stone Bishop’s castle began. Interestingly, the first written record of the castle appears in 1380 concerning the murder of Bishop Heinrich III Biscop. Elected by church officials in 1374, Heinrich III turned out to be very corrupt and was, among other abuses, accused of selling church land and assets to support his mistress’s lavish lifestyle. Ignoring the charges, he left Haapsalu and fled to Kuressaare Fortress’s newly finished Bishop’s castle, with only the loyal members of his staff. A while later the bishop was reported missing. After an exhaustive search of the castle Bishop Heinrich III was found dead in the fortress sewage system, with the garrote still around his neck.

During the 16th century the Bishopric sold the castle to the Danish Empire, which promptly began to improve the castle’s fortifications with the addition of the encircling moat, which established the citadel that exists today.

Early in the 17th century the Danes ceded Saaremaa Island to Sweden. Lutheran preaching which began during the Reformation was now the formal religion of the land and the Swedish government exercised strict control over religious life with regular inspections by church officials to all the congregations across the island called “visitations.” These visits were to “inspect the religious beliefs of peasants and to root out the remnants of paganism and Catholicism.”

With the signing of the Treaty of Nystad at the end of the Great Northern War (1700 – 1721), Sweden ceded all of mainland Estonia and its islands to Russia. Estonia attained a brief independence at the end of WW1 which lasted for 22 years before Russia, as the Soviet Union, returned.

One of the towers of Kuressaare Castle had been used for centuries as a prison. But with the communist Red Army occupying the island in 1940, unheard-of horrors befell the castle, and its courtyard was used as the execution ground for ninety islanders. During WWII, Estonians were forcibly conscripted to fight in both the Russian and German armies. The Nazi Army occupied Estonia from 1941 to 1944. But with the Soviet Red Army advancing again, roughly 27,000 Estonians started a journey to freedom in Sweden from the islands of Saaremaa and Hiiumaa in the fall of 1944, an exodus from their homeland that would become known as “The Great Flight.”

After the Soviet Union annexed Estonia at the end of WWII, the communist regime forcibly deported 30,000 Estonians from every region of the country to Siberia. Few returned. Estonians caught trying to escape Saaremaa Island now were considered “enemies of the state,” and shot by the communist border guards who patrolled the island’s beaches.

In 1994, the fiftieth anniversary of the event, a monument called The Freedom Gate, acknowledging Sweden’s help and Estonia’s gratitude, was erected in Stockholm. The inscription on it reads, “We came in small boats over the sea to escape from terror and dictatorship. Thousands of men, women and children reached the shore, among them workers, fishermen, farmers, intellectuals. We received a warm welcome, we were able to find work and to safely establish homes and families. We did never forget the country from which we were forced to leave and we strove for its freedom. Let the Freedom Gate testify to the humanity and tolerance of the Swedish people towards those who were looking for shelter in evil times and let it commemorate a tiny nation who found here a new home for itself.” By Estonians and Estonian Swedes in Sweden – 1944-1994

The castle’s palace now hosts an interesting museum with exhibits dedicated to explaining the island’s complex history over the centuries. One of the exhibits honors the “Forest Brothers,” a loosely knit group of resistance fighters who opposed the Russian occupation and its security forces. They used their knowledge of the island’s forests and bogs to evade capture by hiding supplies underground in sealed milk cans. They disrupted the Soviet Union’s occupation efforts until most of them were hunted down and killed in the early 1950s. The most famous Forest Brother, August Sabbe, continued the fight, well into his seventies, until he died in a gun battle with KGB agents in 1978.

There is also an intriguing ethnological wing with a large collection of centuries-old island artifacts.

The next day we headed to the lighthouse at the tip of the Sõrve peninsula, only a 45-minute drive from Kuressaare. It was a beautiful drive and along the way we noticed the island’s eclectic bus stops. Some were quite ordinary, while one was lined with bookshelves, and served as a lending library. Another was enclosed with windows and filled with hanging plants. Many were colorfully painted.

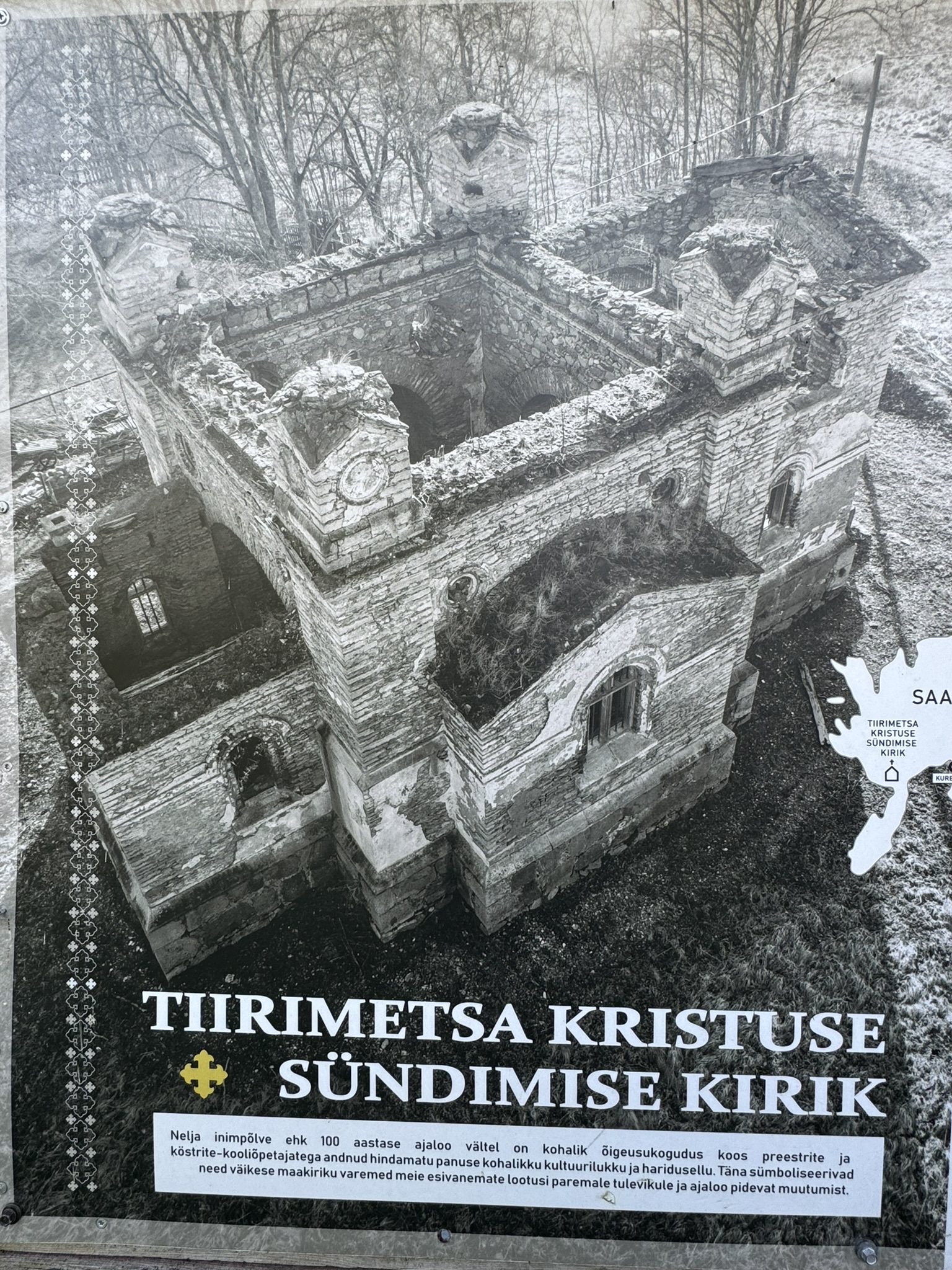

We detoured to the ruins of the Church of the Nativity of Christ in the village of Tiirimetsa, population 50. (A small aside here: a village in Estonia doesn’t necessarily refer to a central collection of buildings. It is often just an area.) It was the first of several historic churches on Saaremaa we planned to see over the next couple of days, but we nearly drove past it, as the ruin was nearly hidden in the shade of a tree line. Built in the 1870s, the once grand Russian Orthodox church was looted and vandalized by soldiers in the Soviet Red Army during WWII. Afterwards during the occupation, the church was used as a barn until the roof collapsed. Tall trees now reach for the sky from its sanctuary.

On the peninsula now, we drove down a serene country lane to the Jämaja kirik, and interrupted a husband and wife team mowing the grounds and vacuuming the sanctuary. Although not expecting visitors, they graciously let us enter. Something led me to believe the woman was the pastor of the church, but there was a language barrier. Donna, herself a pastor, thought I was mistaken. Her reasoning was that no congregation would ask their preacher to also clean. But I couldn’t imagine the congregation of the church being that large anymore, and multitasking might be needed. Built in the mid-1800s over the ruins of an early 13th century church, the historicist style building was very pretty in its pastoral surroundings.

Inside, the church was very bright and since the windows were open you could hear the sound of the sea rolling onto the beach, not far away. The blue tones of the sea are reflected in the church’s altar painting. The church’s cemetery is farther down the lane, on the water edge.

A short distance away we hoped to have our ritual “drive a little then café,” morning coffee at the Family Café at Ohesaare bank, a rocky beach area reached by descending a shallow embankment. It’s a popular spot where folks come to build small cairns, and there are literally thousands of these wobbly stone towers along the water’s edge. There is also a nice example of an Estonian windmill near the café. To our disappointment the restaurant was not open mid-week during the September shoulder season, even though checking its hours on Google Maps indicated otherwise. In the larger towns this wasn’t an issue, but restaurants and cafes reducing their mid-week hours was something we had not anticipated.

When we reached the tip of the peninsula the Sõrve lighthouse towered over us. We didn’t climb it, but instead walked the meditative stone circle near its base. At the water’s edge the sea was perfectly flat with the ebbing of the tide, and the view across the Baltic was endless.

Heading back to Kuressaare we stopped at a park in the village of Salme to investigate some wooden sculptures of people that we had noticed earlier as we drove by. Our closer inspection revealed they were depictions of Vikings. The sculptures link to the accidental discovery, during road construction in 2008 and 2010, of two large Viking burial ships, one 38ft long and the other 56ft in length and dating back to 700 AD. They contained the skeletal remains of 42 warriors plus artifacts, that included swords, spears, arrowheads, and dice in the grave sites. Historians speculate that the Vikings were defeated by the Saaremaa islanders, and that the survivors were allowed to pull the longships ashore to ritually bury their brethren.

Back in Kuressaare we strolled along the harbor’s promenade to the large whimsical sculpture of Suur Tõll ja Piret, a mythic Estonian couple, happily dancing in their birthday suits. The Folkloric heroes are especially beloved on Saaremaa, where legends portray the helpful giant as defenders of the islanders.

The castle was across the harbor, and we couldn’t resist taking some more photos of it in the late afternoon light.

Centuries of religious turmoil have embroiled Saaremaa, starting with the Northern Crusade’s imposition of Catholic Christianity on the islanders in the 13th century and ending with Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation in the 16th century. But it’s left an enduring mark on the island with seven historic medieval churches that still stand, amazingly enough, and are actively used, albeit by a smaller number of worshippers than during their heyday.

We didn’t visit all of them, but we did use them as destinations to work our way across the island to explore other areas. After a tasty breakfast the next morning at Pagariäri | Vanalinna kohvik, a bakery and café in old town Kuressaare, we headed to Kaarma Church. Originally dedicated as The Peter and Paul Church, it dates to the late 1200s, making it one of the oldest churches on the island. The church was originally built without a steeple, as was the style at the time. But any structure this old was bound to have withstood numerous alterations and additions over the centuries. The church underwent its first major alteration in the 15th century, when the bell tower – the first on the island – was added to its façade. Later heavy buttresses were added on either side of the church entrance to prevent the front wall from collapsing. The inside was quite intriguing with a pulpit from 1645 and wonderful carved wood sculpture of St. Simon of Cyrene, along with other interesting pieces and primitive stone carvings.

Afterwards we headed to see the windmills we had zoomed past the day we arrived on the island. In use on Saaremaa since the 14th century, there were nearly 900 of the iconic windmills, or one for every two farms on the island by the early 1900s. In 1925 Angla was a prosperous village with 9 privately owned windmills built across its highest point to catch the wind for the mills to grind the grains harvested from the hamlet’s 13 farms. Most of the windmills across the island did not survive WWII, and many of the ones that did were left abandoned after “The Great Flight,” which saw the depopulation of the island. After Estonia’s 1991 independence, Alver Sagur acquired the property with the village’s remaining 5 windmills, and spent years restoring them with parts salvaged from other ruined mills from across the island. They are now the centerpiece of the Angla Windmill Hill and Heritage Cultural Center which Sagur envisioned to preserve Saaremaa’s unique agrarian culture.

Four of them, the oldest dating to the early 1880s, are post mills typical to Saaremaa, where the whole windmill turns around a central post to bring the sails into the wind by physically moving the long arm projecting from its side. While the other one, built in 1927, is a Dutch mill, where only the top which houses the sail’s gear shaft rotates around the stationary base.

Only one windmill has been totally restored to working order and still is used occasionally to grind grain, and you are allowed to climb the ladders between floors to examine its inner workings. The museum also had an interesting collection of historic agricultural equipment. The center’s restaurant was also good, and we really enjoyed their coffee.

We did a quick detour to the old Russian Orthodox Church in Leisi, which was built in 1873, and has those distinctive orthodox crosses atop its domes, before backtracking to the medieval Karja church, only minutes away from the windmills.

Noticeably the church, from 1254, was built without a steeple, which was a common style for fortress sanctuaries in the 13th century. There was another car in the driveway, though we didn’t see anyone, and the church was locked. Next to the door was a wonderful carved stone relief sculpture with rustic figures. Posted on the door was the caretaker’s phone number, but no one answered when we called. But luck was with us, and as we were just turning to leave two people appeared walking down the driveway. One was waving a set of keys.

Inside, more relief carvings decorated some of the interior’s architectural elements.

Along with an elegant altar there were some partial remnants of medieval era decorative paintings, faded but still visible on the walls.

On the way back to Kuressaare we turned off the main road to visit the church in Valjala, the oldest preserved stone sanctuary in Estonia. Construction of the church started in 1227 after the Livonia Crusades of the 13th century, which forced Christianity on the pagan indigenous populations of Saaremaa Island and the northern Estonian mainland. The islanders didn’t convert willingly and their resistance was fierce, requiring the church to be expanded and fortified by the end of the century.

The entrance to the church looked more like a door to a medieval castle, ready to repel any attempted siege, and of course it was locked, a dilemma that was fortuitously resolved with the arrival of a middle-aged woman coasting to a stop on her bicycle. With a friendly greeting, she unlocked the door and vanished as quickly as she had arrived. The sanctuary was dimly lit with ambient light from its tall narrow windows, which dramatically highlighted the sculptural wall decorations. There was also a highly carved Romanesque baptismal font that is believed to be original to the church and is thought to be one of the oldest pieces of carved stonework in Estonia. In the 17th century the church’s tower was added. Three centuries later lightning struck the tower and destroyed its steeple.

We locked the door behind us when we left and when we reached our car, parked across the street, turned to look back at the church. Our mysterious bike rider had returned to check the lock, “Thank you,” she called. We waved.

That evening, our last night in the village, we wandered about with no particular restaurant in mind, simply enjoying the town’s warm ambience on a nice fall day. We checked Saaremaa Veski, a restaurant located in a beautiful historic 1899 Dutch-style stone windmill. However, it was only open on the weekends during the shoulder season. Further on we came across the sculpture of a giant hand called “Suure Tõllu käsi,” the Hand of Suur Tõll, which playfully references the beloved folkloric hero always giving the islanders a helping hand. The artistic work with its abstract background subtly reminded us, after several days of exploring medieval churches and a castle, that we were still in the 21st century.

“Oysters,” prominently displayed on the placard in front of Vinoteek Prelude drew us inside. Rustically finished with stone walls and roughhewn ceiling beams, the restaurant had a wonderful warmth enhanced by candles lit on the tables. The menu featured locally sourced produce, fish and game meats, along with an extensive wine list. The oysters were fantastic, though they were imported from Brittany, as the shallow waters of the Baltic Sea stay too warm and are not salty enough to grow them.

The next morning, we were up early to explore the eastern part of the island before catching a late afternoon ferry back to the Estonian mainland and continuing on to Pärnu for the night.

Miraculously, the door to the Pöide church was open! Some renovation work on the tower end of the church was underway, and workers were erecting scaffolding. The early history of the first churches on Saaremaa tends to be quite confusing with overlapping dates. But it seems the ancient church in Pöide vies with the Valjala Church as the oldest Christian place of worship on the island, each being quickly built shortly after the conclusion of the Livonian Crusade, in 1227. The original Pöide chapel was the only surviving part of a Livonian castle destroyed during the St. George’s Night Uprising of 1343, which saw the indigenous islanders kill their German and Danish overlords, and “drown the priests in the sea.” The folks seeking refuge at the Pöide castle withstood a siege for eight days before surrendering their weapons, with the assurance they would not be used against them. They were lied to and when they exited the castle the islanders stoned them to death. By the end of the 13th century the Livonian Order had reconquered Saaremaa and the small original chapel was expanded to the east and west. At this time the roof was raised and vaulted. When the fortified tower was added it became the largest medieval church on the island.

The inside is cavernous and at one time had enough pews to seat 320 parishioners.

In 1940, on the day that Estonia was forced to become a member state of the Soviet Union, lightning struck the church’s tall spire that was erected in 1734. Some considered it an omen of future difficulties. The church did not fare well during WWII with Soviet troops looting anything of value, and burning the pews for firewood, before it was used for decades as a hay barn. Only some sections of early painted wall ornamentation and the heaviest stone architectural artifacts were left untouched. One of the pieces to survive is the ledger stone of a local Saaremaa knight entombed by the altar, its carving now partially worn away by centuries of footsteps over it. Today the church holds services twice a month and hosts religious music concerts.

There was no missing the onion top domes of the Russian Orthodox Neitsi Maarja Kaitsmise in the small crossroads village of Tornimäe. The 1873 church’s setting on a small rise above the village wonderfully highlights its beauty. With the signing of the Treaty of Nystad to end the Great Northern War in 1721, Sweden surrendered Estonia to Peter the Great’s Russian Empire. Originally the Orthodox church had an insignificant footprint on Saaremaa, but that changed in the mid-1800s with the unfounded rumors that the church would give land to the islanders, mostly Protestant serfs, if they converted to the Orthodox church. Consequently, nearly 65 percent of the island’s Protestant rural peasantry fell victim to this deception, and converted to the orthodox religion, in the false hope of attaining their own land.

Down the hill from the church, we parked at Meierei Kohvik, a small café, one of the only two businesses in the village, for lunch. I was driving and had just turned off the ignition when Donna asked if I heard the car horn blaring. I’ll admit that I am slowly going deaf, and even with the help of hearing aids still have difficulty. “No. It must be from that truck over there.” “It’s from our car and it’s very loud,” she responded. By this point on our trip we had been driving the car, without any trouble, for over a week, so this was new issue. It turns out that that I inadvertently pressed something on the key fob, but no combination of pressing buttons would undo it. Unfortunately, to our dismay, the car’s manual was totally in Estonian too. So, there we were sitting in the car in the middle of Saaremaa island with the horn blasting away. I was totally useless in this situation. Fortunately, Donna resolved the problem by doing a quick internet search. Peace and quiet reigned once again. The café was simply furnished, but the food, pastries and coffees were very good. They also had a nice selection of apple juice and cider produced on Saaremaa available for purchase.

We arrived to Illiku Laid, a small thumb of land protruding into the Vaike Strait which separates Saaremaa from its smaller eastern neighbor, Muhu Island, with hopes of seeing From the Sea, an environmentally conscious sculpture, depicting human-like creatures emerging from the water. It was created by the Estonian artist Ines Villido using lost fishermen’s nets and other garbage retrieved from the sea. It was created several years earlier for the annual 4 day I Land Sound festival that’s held on Illiku Laid every July. The festival is the event that turns this sleepy backwater into Estonia’s version of Burning Man and “brings together artists, musicians, and creatives from around the world, fostering cultural exchange and collaboration, with a strong emphasis on environmental sustainability and community engagement.” Disappointingly, the sculpture was not there, but on tour as part of an environmental awareness campaign. Though we did realize we had seen one of Villido’s other works, Trust the Whale during our wanderings in Kuressaare. Her Cigarette Butt – Stand Up Board, made with 29,000 butts collected during the 2019 festival, was on display along the waterfront.

Saaremaa Island receded in the rear-view mirror as we followed the road across the Väinatamm, a long narrow causeway and bridge that connects Saaremaa to Muhu, before ending at the Praamid ferry terminal in Kuivastu. The day had passed quickly, and we arrived in time to take an earlier ferry to Virtsu, on the Estonian mainland. We had purchased our tickets for a later crossing, but there were enough open cars spaces that we were allowed to drive aboard. There was barely enough time to climb to the observation deck before the ferry’s 30-minute crossing concluded. We headed to the coastal city of Pärnu for an overnight stay before continuing our travels to Riga, Latvia.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna

Paradise is such a subjective feeling and if you don’t require a turquoise blue sea and white sand beaches, Antigua, Guatemala just might fit the bill. This charming colonial city with its ever spring-like weather was perfect for our two-month stay.

Paradise is such a subjective feeling and if you don’t require a turquoise blue sea and white sand beaches, Antigua, Guatemala just might fit the bill. This charming colonial city with its ever spring-like weather was perfect for our two-month stay.  We arrived in Antigua at the end of October so that we could attend the Sumpango Giant Kite Festival held every year on November 1st, All Saints Day. That spectacularly colorful event and a religious procession that burst forward from La Merced Church on October 28th would prove to be representative of the people and life in Guatemala we experienced.

We arrived in Antigua at the end of October so that we could attend the Sumpango Giant Kite Festival held every year on November 1st, All Saints Day. That spectacularly colorful event and a religious procession that burst forward from La Merced Church on October 28th would prove to be representative of the people and life in Guatemala we experienced.

On Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays the market tripled in size when the outdoor portion was open, and farmers brought in truckloads of fruits and vegetables from the surrounding villages. There we experienced one of the best markets going, set in a bustling, dusty lot with Volcans Agua, Fuego and Acatenango touching the sky in the background. Most produce was sold in quantities of 5 quetzals (60 cents) so bring lots of small bills, as vendors didn’t usually have change for anything larger than 10Q. The flavor of the locally grown vegetables was amazing. Being backyard gardeners ourselves, we were duly impressed. Twenty quetzals would buy enough vegetables for a week.

On Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays the market tripled in size when the outdoor portion was open, and farmers brought in truckloads of fruits and vegetables from the surrounding villages. There we experienced one of the best markets going, set in a bustling, dusty lot with Volcans Agua, Fuego and Acatenango touching the sky in the background. Most produce was sold in quantities of 5 quetzals (60 cents) so bring lots of small bills, as vendors didn’t usually have change for anything larger than 10Q. The flavor of the locally grown vegetables was amazing. Being backyard gardeners ourselves, we were duly impressed. Twenty quetzals would buy enough vegetables for a week.

Shopping at the local supermarket, La Bodegona, was a wonderfully hectic experience. At times it could feel like you were shopping from a conga line, weaving up and down aisles, afraid to leave the line for fear of not being able to enter it again and being stuck in dairy for eternity. Numerous store employees lined the aisles offering samples of cookies, deli meats, drinks and other temptations to keep the energy level of the beast alive. It was a hoot! We had to psych ourselves up, like players before the big game, to shop there because it was so hectic and required a certain mental and physical stamina. I will confess though to dancing in the checkout line to blaring Latino Christmas music – the mood was contagious.

Shopping at the local supermarket, La Bodegona, was a wonderfully hectic experience. At times it could feel like you were shopping from a conga line, weaving up and down aisles, afraid to leave the line for fear of not being able to enter it again and being stuck in dairy for eternity. Numerous store employees lined the aisles offering samples of cookies, deli meats, drinks and other temptations to keep the energy level of the beast alive. It was a hoot! We had to psych ourselves up, like players before the big game, to shop there because it was so hectic and required a certain mental and physical stamina. I will confess though to dancing in the checkout line to blaring Latino Christmas music – the mood was contagious.  On the same block D&C Cremas, a Walmart affiliate, offered a more sedate shopping experience. Both supermarkets had excellent poultry, which was more tender and tastier than back in Pennsylvania. We were also fortunate that a pork butcher opened a new shop a half block away and offered fresh meat and sausage daily. We enjoyed all the different varieties of Guatemalan sausage he made and found them to be very flavorful and lean, with almost no fat.

On the same block D&C Cremas, a Walmart affiliate, offered a more sedate shopping experience. Both supermarkets had excellent poultry, which was more tender and tastier than back in Pennsylvania. We were also fortunate that a pork butcher opened a new shop a half block away and offered fresh meat and sausage daily. We enjoyed all the different varieties of Guatemalan sausage he made and found them to be very flavorful and lean, with almost no fat.

The next day we a followed a serpentine mountain road, second gear all the way, up to Santo Domingo del Cerro, a beautiful sculpture and art park with museums, walking trails and a restaurant that overlooks Antigua. Plan on spending at least a half day there, because it is a beautiful setting for a restful day or afternoon. Casa Santo Domingo offers a free hourly shuttle to the park from the hotel in town.

The next day we a followed a serpentine mountain road, second gear all the way, up to Santo Domingo del Cerro, a beautiful sculpture and art park with museums, walking trails and a restaurant that overlooks Antigua. Plan on spending at least a half day there, because it is a beautiful setting for a restful day or afternoon. Casa Santo Domingo offers a free hourly shuttle to the park from the hotel in town.

Antigua filled early with people in all their finery on New Year’s. Vendors selling textiles the day before were now offering party hats and all sort of 2019 memorabilia. Concerts were held in Plaza Mayor and under El Arco. Firework launchers were being setup amidst the crowds in the streets. Families were picnicking in the park and folks were staking their spots early to watch the fireworks later. At midnight a loud and colorful display filled the night sky. We could hear the roar of an appreciative crowd from our rooftop. We heard random explosions throughout the night to sunrise. Guatemalans love their fireworks!

Antigua filled early with people in all their finery on New Year’s. Vendors selling textiles the day before were now offering party hats and all sort of 2019 memorabilia. Concerts were held in Plaza Mayor and under El Arco. Firework launchers were being setup amidst the crowds in the streets. Families were picnicking in the park and folks were staking their spots early to watch the fireworks later. At midnight a loud and colorful display filled the night sky. We could hear the roar of an appreciative crowd from our rooftop. We heard random explosions throughout the night to sunrise. Guatemalans love their fireworks!