Just below the northern horizon, a white brushstroke highlighted the verdant canvas before us as we savored the view from the top of the castillo in Castellar de Frontera one last time. That swath of white slowly changed into Jimena de la Frontera as we drove closer. One of Andalucia’s famed Pueblos Blancos, the village is set on the hillside below the ruins of its ancient castle which once protected it.

In ancient times the homes in villages featured roughhewn stone masonry. Lime paint was a luxury, until its use was greatly expanded during the mid-1300’s when a bubonic plague pandemic swept through the Mediterranean countries. Residents of villages were required yearly to cover the outside and the interiors of their homes and churches with a limewash, known for its natural anti-bacterial and insecticidal properties, in an effort to reduce the spread of disease. Community inspections were done, and folks were fined for noncompliance. This mandated conformity was eventually appreciated as an aesthetically pleasing look and a symbol of meticulous tidiness. Fortunately, the custom stayed and has become an iconic signature of southern Andalusia.

Villaluenga del Rosario was our ultimate destination for the day, but before that we would be driving through the expansive forests of Parque Natural Sierra de Grazalema and stopping along the way in Ubrique, and Benaocaz. All pueblos blancos, though all different in size, setting and atmosphere. According to our maps app the trip would take 2 hours. But it was a glorious 58-mile sinuous route through the mountains, and with several stops it took us most of the day.

The vast 130,000-acre Parque Natural Sierra de Grazalema, with peaks reaching 5400 feet, is one of the wettest areas in Spain, receiving almost 80 inches of rain a year. This is surprising, considering that many areas in Andalucia are often used to replicate the American southwest for European filmmakers. These wet conditions over many millennia have created a dramatic karstic landscape of shear mountains, lush valleys and caves, especially Pileta Cave with its 30,000 year old prehistoric paintings. The park’s lower elevations feature forests of cork oak, carob, hawthorn, and mastic. Higher slopes transition to a landscape of gall oaks and Spanish fir, a tree species that survived the last Ice Age. This ecosystem supports a diverse fauna that contains 136 species of birds, most notably a large population of griffon vultures, and 42 mammal species, that include foxes, badgers, roe deer, otters, and Spanish ibex. And in ancient times it was the refuge of wild, now extinct, aurochs, the ancestor of the famous Spanish Fighting Bulls, toro bravo. The park has been a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve since 1977.

Farmers still harvest cork and olives amidst the rocky terrain and graze cattle, sheep, and goats within the park. This practice made for an interesting encounter when we rounded a curve and faced a VERY LARGE BULL standing in the middle of the road, adjacent to some pasture. We stopped, looked around for his farmer, but there was no one in sight. It was obvious he was the king of this domain, with no intention of moving aside until he felt like it. Slowly we inched forward and watched him eye us until he decided to saunter across the road and let us pass.

Ubrique is a large thriving town with 17,000 inhabitants set in a valley surrounded by tall peaks and steep scree slopes, its homes built above and around boulders too large to move. The town’s prosperity comes from its fine leather workshops, which account for 60% of the townspeople being employed directly or indirectly in the creation of leather products. It started simply enough with leather cases and pouches to carry tobacco and the Precise, a heavy-duty strap that allowed workers to safely carry silex stones and iron bricks.

By the mid-1700s their fine leather products and artisanal craftsmanship was recognized across Europe which fueled an export industry. The good fortunes of the town continued to grow until the mid-2000 when clients seeking higher profit margins moved their leather goods production to China and other Asian countries. Fortunately, their exodus did not last long, and they returned to Ubrique when they realized that the excellent craftsmanship in this small Andalucian town could not be rivaled by cheap labor. Today Ubrique is considered the “artisanal leather capital, “ for high-end fashion brands like Chloe, Gucci, Hermes and Louis Vuitton. “So many stores, so little time.” Of course, we shopped! The decision-making process was painful, but Donna managed to select one single beautiful purse to take home.

In March the twisting roads, higher into the mountains, were nearly void of traffic. Occasionally a campervan passed. Reaching Benaocaz, we parked and strolled through a nearly empty town square in search of coffee. It was a quiet weekend afternoon in the shoulder season, and few people were about, but luckily, we happened to come across Restaurante Nazari, a rustic restaurant with outside tables that had a view of the valley below the town.

Villaluenga del Rosario was only a little farther, and higher into the mountains. The village is dramatically set along one side of a narrow green valley at the base of a sheer mountain massif. The lane to our inn, the Tugasa La Posada, looked too narrow to drive down, and I was concerned about getting to a point that required backing up. A difficult task in an alley barely wider than our rental car, and there was plenty of parking above the village. La Posada wonderfully reflects the typical inn of centuries past, with a large tavern, featuring regional recipes, on the ground level and a handful of rooms above.

Several things are unique to this pueblo: Snowy winters are common in the Sierra de Grazalema Natural Park’s highest village, situated at an elevation of 2800ft. It is also the smallest village in the Province of Cadiz, with only 438 residents. And the village has a unique octagon shaped bullring, built around a natural rock formation, that is the oldest in Cadiz Province, dating from the mid-1700s. The exact year of construction for the bullring isn’t known, as the town’s archives were lost in a 1936 fire. Located on an important cattle trading route through the mountains, the bullring was also used as a corral during livestock festivals.

But before domestic cattle were raised in the area, prehistoric people used to pursue auroch, a wild bull that lived in the Sierra de Grazalema until it was hunted to extinction in the Middle Ages. Nearby in Cueva de la Pileta, primitive cave paintings of bulls have been dated to the Paleolithic era 27,000 years ago. The famous fighting bulls of Spain, Toro Bravo, descend from this primal auroch lineage that once roamed wild. Ancient pagan festivals often conducted a running of the wild bulls, tethered to a group of men by a long rope, through their villages before a ritual sacrifice. “Toro de Cuerda'”(Bull on Rope) festivals, are thought to be the foundation of the modern Spanish Bull Fight, and are still held in Villaluenga del Rosario, Grazalema, and Benamahoma. With the advent of Christianity some of these pagan elements were incorporated into church celebrations of a pueblo’s patron Saint. In Grazalema the early church Christianized the practice and includes the Feast of the Bull in celebrations to the Virgen del Carmen every July. Benamahoma’s “Toro de Cuerda” is held in August during their festival to honor the town’s patron saint, Anthony of Padua.

This tranquil village has gone through some turbulent times in its past. Villaluenga del Rosario, known for its woolen textiles in the 17th century, did not escape Napoleon’s destruction as his troops retreated across the mountains after they abandoned their siege of Cadiz in 1812. French troops sacked the village and torched the old Church of El Salvador. Now only the walls and roof arches remain, open to the sky. The sanctuary is now used as a cemetery. The economy declined throughout the region in the 1800s and early 1900s, and the mountains were beset with bandits. Notoriously, José María El Tempranillo and Pasos Largos, the most infamous of the Sierra’s outlaws, would frequent the village and hideout in the surrounding caves. They are celebrated as Robin Hood bandoleros, robbing the wealthy and redistributing their stolen goods to help the poverty-stricken locals – Andalucia’s mountain justice. These same caves in the 1930s would shelter Republican resistance fighters escaping Fascist troops during the Spanish Civil War. A hiking trail, Los Llanos del Republicano, from the village to caves is named after them.

The rural population continued to emigrate, contributing to further economic deterioration until the villages’ employment prospects improved with the opening of a cheese factory, Queso Payoyo, in 1997. The Payoyo goat is an ancient breed from the Sierra de Grazalema and considered endangered. Since Queso Payoyo opened 25 years ago, its goat and sheep cheeses have received 175 national and international awards. Thirty-five farms now supply Payoyo goat and Merina grazalemeña sheep milk to the cheesemaker. Their shop just across the road from the village seems to be a Mecca for cheese aficionados. Open seven days a week, we were surprised to find it packed with customers early on a Sunday morning, when we stopped to buy some cheese before we headed to Benamahoma.

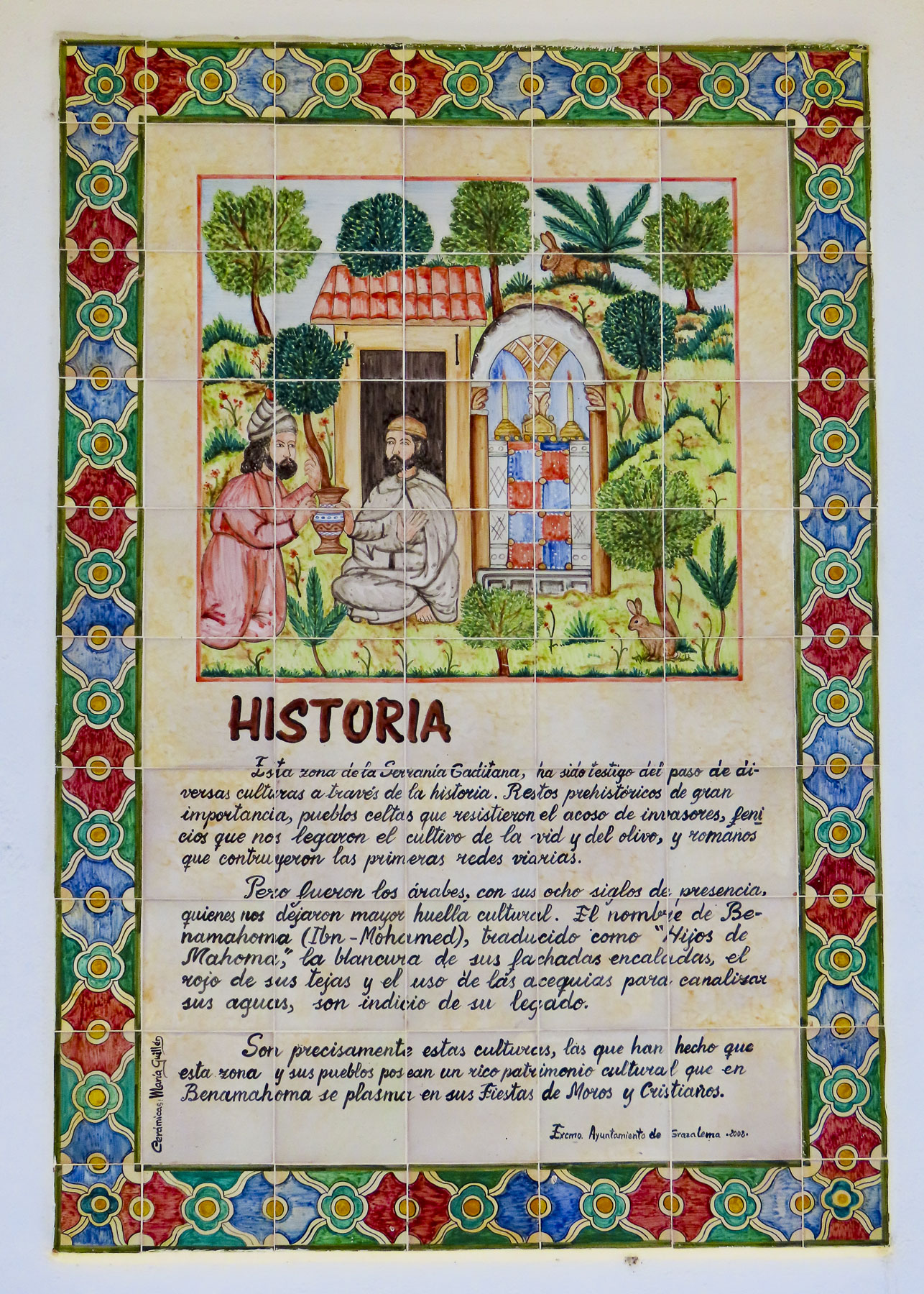

It was a beautiful crisp spring day, and we enjoyed a slow walk uphill into the village. Next to the Plaza de las Huertas the façade of the Ermita/mezquita de San Antonio, a church/mosque, visually represents Benamahoma’s complex cultural identity, with Moorish horseshoe-shaped arches and three golden spheres topped by with a gold crescent, typically seen on minarets, atop its tower.

This region in Spain has a very complicated history, beginning with Alfonso X’s Reconquista which started in the mid-1200s, paused, then continued for the next 400 years with his successors. Benamahoma was the last Moorish village in the mountains to have its inhabitants expelled from the region in 1609, eighteen years after Grazalema’s Muslim villagers were forced out, though the hamlets are only nine miles apart. Their reprieve was caused by the fact that although Alfonso X and later Kings achieved military victories, they did not have enough troops to garrison each village, nor sufficient numbers of willing Christian settlers from Northern Spain to repopulate the conquered towns. Consequently, to keep the economy of the area going and subjects to collect taxes from, Moors were allowed to stay as long as their local Princes swore allegiance to a Christian King and declared themselves loyal vassals. This did not always go smoothly and there were rebellions. Most famously the Mudéjar Revolt in 1264, when the towns of Jerez, Lebrija, Arcos, and Medina-Sidonia were recaptured and occupied by Moors for several years before Christian armies secured the towns once again.

Benamahoma’s historic, pragmatic tolerance is celebrated the first weekend every August with a Moros y Cristianos Festival. Carrying swords, shields and blunderbusses, historical reenactors dressed in period clothing parade through the village to the bullring, where they then engage in mock hand-to-hand combat. The battles are won with the capture of an image of San Antonio de Padua by the Moors on Saturday and then won by Christians on Sunday with the rescue of his image. Many of the positions in the opposing armies are hereditary, the tradition being passed down from father to son, through the generations. Benamahoma is the only village in western Andalucia which celebrates this festival.

This village’s remoteness in the Sierra de Grazalema did not protect it from the atrocities committed during the Spanish Civil War. Near the bullring, in the Parque de Memoria Historica, silhouettes stand where villagers once stood against a wall before they were massacred by Fascists. Sadly, this memorial is also near the village’s second church, the Iglesia de San Antonio de Padua.

Backtracking as we headed to Arcos de la Frontera, we stopped at a radio station above El Bosque. A trail behind its tall antenna offered the perfect vantage point to capture a photo of the village below. We did not stop in El Bosque, but after catching glimpses of the village as we drove through, in hindsight we wished we had. But there was a time constraint, we wanted to spend the afternoon exploring Arcos de la Frontera, before flying on to Barcelona the next morning.

The A-372 between El Bosque and Arcos de la Frontera has to be one of the prettiest stretches of highway anywhere. With the reflection of the Sierra de Grazalema in our rearview mirrors, we wished we could have lingered longer.

I’ve always loved maps for researching routes, finding obscure sites, and figuring out the best vantage point to capture a landscape from. This brought us to our first two stops at the Molino de Angorrill, an old mill, and the Mirador Los Cabezuelos, before we entered the hilltop citadel. Both places along Guadalete River had wonderful views of the ancient city.

After this our map app failed us when it suggested we head the wrong way down a one-way calle into the village. We eventually found an underground parking garage at Parque El Paseo and towed our suitcases uphill to the Parador de Arcos de la Frontera.

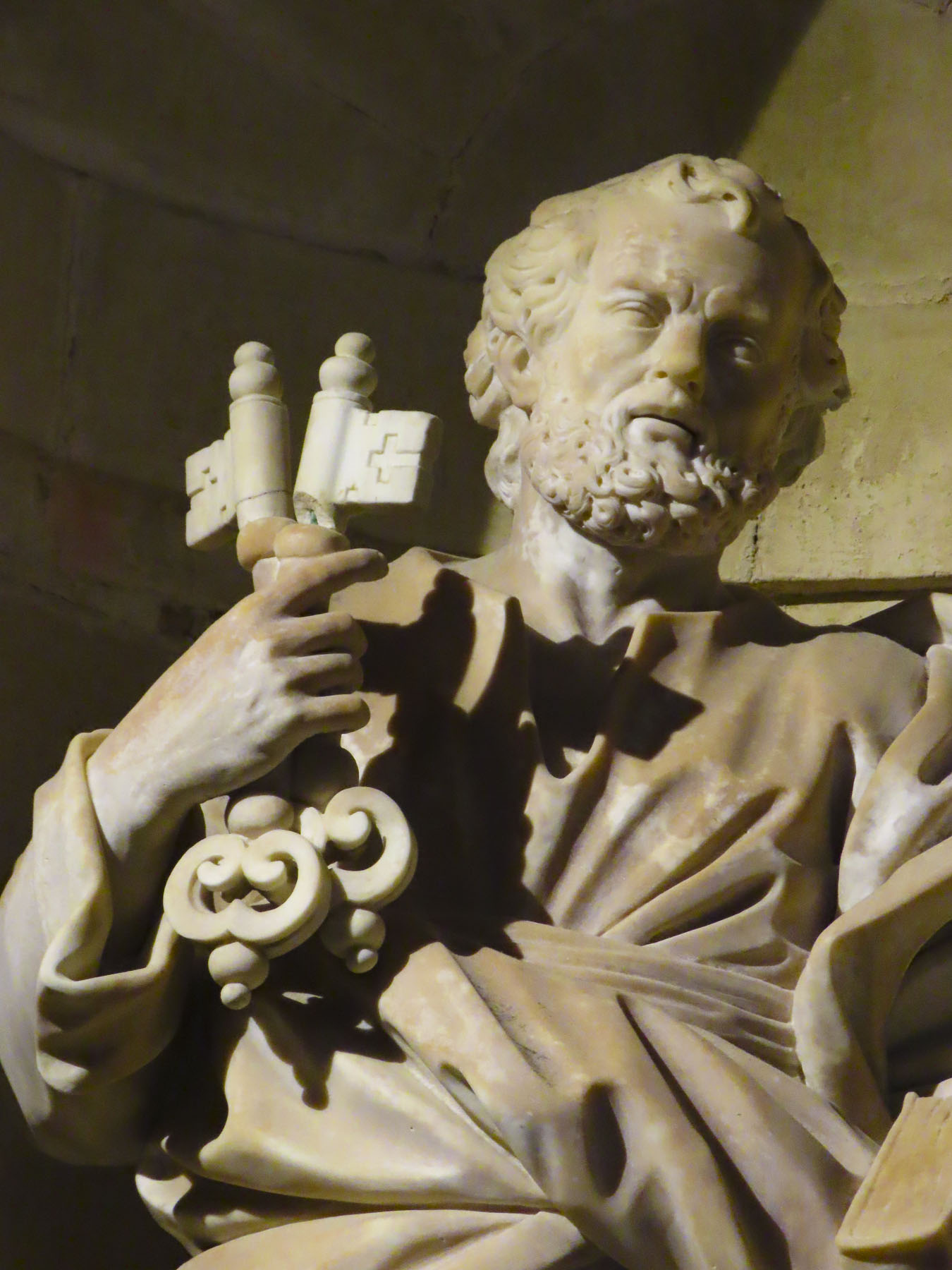

It was LONG walk, but of course we stopped frequently to take photos. Located next to the 500-foot-high Mirador Plaza del Cabildo and adjacent to the Basílica de Santa María de la Asunción and the Castillo de los Duques de Arcos, the hotel was a perfect base for a one-night stay. Formerly the Casa del Corregidov was an Andulcian palace before it was acquired by the government and renovated to be a parador in 1966.

Arcos has always been a favored spot, appreciated for its access to abundant water sources and its easily defensible position atop a cliff face. It has hosted settlements since the Neolithic period, Bronze Age, Tartessians, Phoenicians and Romans periods.

The village continued to grow under the Moors and while the facades and interior of buildings in this ancient town have changed over the centuries the original Arab footprint of the village, with its exceedingly narrow lanes has remained the same.

The view from the mirador and the hotel’s patio were phenomenal during the golden hour. As the sun was setting, a large flock of storks appeared over the bell tower of the Basilica and circled for about fifteen minutes before flying away. It was a magical experience that nicely capped our short time in Arcos.

The next morning, we watched the sun rise over the Sierra de Grazalema and the village’s church steeples from our hotel room, before wandering through the village’s ancient lanes one last time.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna