We had been in the Balkans almost two weeks by now, and this was the first time we encountered heavy traffic. Without realizing it we had planned on driving from Sarajevo to Mostar on May 1st, Labor Day, a major two-day holiday in Bosnia, where it is traditionally spent picnicking and relaxing with family and friends in the countryside. It was a warm beautiful spring day, and did in fact feel as if every family in Sarajevo was heading to Mostar, in the southern Herzegovina region, turning what would normally be a two-hour drive into five.

Our journey was off to a good start as we headed southwest on the A1, from Sarajevo through the rolling foothills of the Dinaric Mountain Range, a wide 644km (400mi) long stretch of peaks that runs southeast from Slovenia through Croatia, Bosnia, Montenegro, Serbia, Kosovo, Albania, and North Macedonia. But it soon slowed as this major four-lane wide infrastructure project, which will eventually reach the Adriatic coast, narrowed for construction projects. The countryside was lush with fresh spring greenery, though disappointedly there were not any scenic pullovers along the way, and we contented ourselves as best we could, by taking landscape photos through the window of our car as we drove.

Our “drive a little then café” yearning for caffeine was seriously overdue, so we detoured slightly to Restoran Vrata Hercegovine for coffee and lunch when the A1merged into the two-lane E73 at the traffic circle in Bradina. They had a large menu to select from and everything we ordered was very good; the pricing very budget friendly.

From here the E73 basically follows the Trešanica River, the headwaters of which flow from the slopes of Mt. Bitovnja 1,700m (5600ft) which wasn’t far from where we stopped for lunch, to Konjic where it merges with the Neretva River at Konjic before flowing into Lake Jablanica. We had originally planned to have lunch here and walk across the Stara Ćuprija, Konjic’s old Ottoman bridge, a six-arch stone span constructed in 1682. The bridge is 107km (66mi) downstream from the river’s source on the slope of the Zelengora mountains near Mt. Maglić 2,388m (7835), Bosnia’s highest peak on the border with Montenegro. Nearer to Konjic is Glavatičevo, a popular village for river rafting on the Neretva.

The road roughly traces Lake Jablanica’s picturesque shoreline. The large lake is actually a manmade reservoir that is 30km (19 mi) long and covers 67.5 square kilometres (26.1 sq mi). The damming of the upper portion of the Neretva River was created between 1947 and 1955 to supply hydroelectric power to the region. While this was the first dam built on the Neretva River there are now many environmentally controversial proposals to block the remainder of free-flowing waterway with 50 more dams across the river and its tributaries. In Ostrožac there was a nice beach where we stopped to take photos of the Lake.

South of the lake we detoured to the Old Neretva Train Bridge in the town of Jablanica, an important site during the “Battle of the Wounded” during February–March 1943. Here Josip Tito led the escape of over 20,000 Yugoslav Partisans, plus roughly 4,000 wounded, east across the Neretva River to escape the pursuit an overwhelming Axis force assembled to destroy them after their unexpected victory at Prozor.

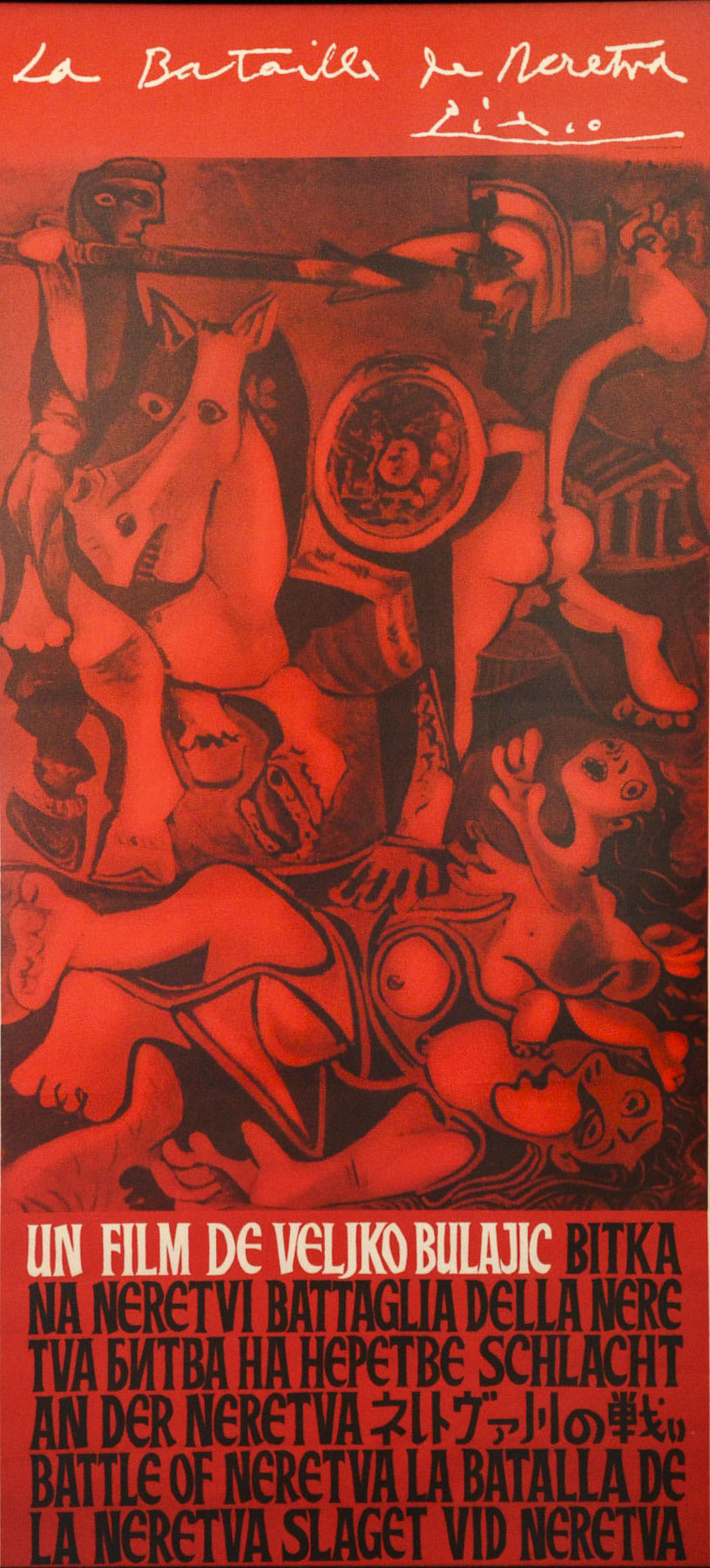

This successful strategic retreat relied on a deception which required the destruction of all the bridges across the Rama and Neretva rivers between March 1stand 4th. This action led the Axis forces to believe the partisans were headed towards northern Bosnia, while in fact Tito was leading his men to safety on March 7th and 8th across a temporary wooden bridge built across the Neretva, in just 18 hours, after the rail bridge was destroyed. A museum at the site commemorates this history. As does the 1969 movie “The Battle of Neretva” starring Orson Welles and Yul Brynner, among an international cast by directed Veljko Bulajić. The film was a contestant in the best foreign film category in the Academy Awards that year. The European film poster for the movie was famously designed by Pablo Picasso, in which he used motifs of his painting “The Rape of the Sabine Women” but “painted them red to symbolize the anti-fascist fight for freedom.” It’s one of the two movie posters that Picasso ever designed. The artist refused payment, instead requesting 12 bottles of Yugoslavia’s finest wines gathered from across the region.

Our 55km (34mi) drive from Ostrožac on Lake Jablanica to Mostar paralleled the river as it coursed through rugged gorges on its way to the Adriatic Sea and was gorgeously scenic, pun intended.

There is time-limited metered street parking in Mostar’s old town near the historic old bridge, Stari Most. Many folks decide to visit Mostar as part of a guided day trip from Sarajevo, Dubrovnik & Split, Croatia or even as far afield as Kotor, Montenegro. We chose to base ourselves in the Hotel Kriva Ćuprija for four nights to enjoy Stari Grad, the old town, and explore the region. We parked in a convenient monitored lot at the foot of Onešćukova that the hotel recommended. The view from our room looked out over slate roofs, a mosque, and an old stone bridge.

The 1990s war in Bosnia brought total devastation to Mostar, where an estimated ninety percent of the buildings were destroyed by forces bombarding the city from the surrounding hilltops. Mostar was once a tiny hamlet along the Neretva River, before the Ottomans seized it and transformed it into an important multicultural trading center and frontier garrison town during their 15th century conquest of Bosnia. The site where the hotel stands overlooking the Crooked Bridge, Kriva Ćuprija, from which it takes is name, was an ancient dwelling, and the hotel is a modern reconstruction of Stari Grad’s historic “Turkish houses” – residential buildings of stone and wood that defined the Old Bridge Area’s pre-war heritage. While the famous 15th century Stari Most bridge was destroyed in the 1990s war, the Crooked Bridge amazingly survived the conflict but succumbed to raging flooding in 2000 and was subsequently rebuilt.

Reconstruction of Mostar began with funds from the European Union, the World Bank, and UNESCO shortly after a permanent ceasefire was established with the Washington Agreement on March 18, 1994, nineteen months before the cessation of the wider Bosnian conflict was resolved with the signing of the Dayton Peace Accords on November 1, 1995.

Old Town Mostar is beautifully atmospheric and while most of the buildings in the Stari Grad have been fully restored, several owners have chosen to leave the numerous bullet marks on the sides of their buildings as reminders of the wrath of war. Throughout the city there are still over 1,000 buildings in ruin or abandoned as a result of the conflict, with many of them concentrated across the river in east Mostar.

Cobblestone alleys twisted through Stari Grad and we followed them all to soak in the ambiance. Visiting the old town was a sensory experience: dazzling color, aromas of grilled meats, textures and the melancholic song of the call to prayer that the muezzin sings from the minarets dotted around the city.

Our wanderings took us over the high arched, Ottoman built Stari Most. The iconic symbol of Mostar was a vital lifeline used by soldiers and civilians to transport food, medicine, and arms to besieged areas of the city on the west bank Neretva River during the 1190s war. It’s a popular area where folks gather to hopefully watch divers jump from the bridge 28m (92ft) into the cold water below, a decades old tradition that started in 1968. None of the divers were working the crowd for tips when we crossed. Diving from the bridge has also existed for 450 years as a traditional rite of passage for young men, and as an old legend says, “the way a boy becomes a man in Mostar.”

Across the bridge the lane narrowed through the Kujundžiluk alley. Known as the old goldsmiths’ quarter, it served as a crucial trading alley for merchant caravans before they paid customs duties to cross the bridge during the Ottoman era. Our “walk a little then café’” philosophy took us to the restaurant Urban Taste of Orient. Their beautiful terrace offered spectacular views of the river and Stari Most. We were enjoying a charcuterie board of Bosnian cheeses and cured meats when I looked at the bridge and noticed a lone man, seemingly much taller than the rest of the folks, who from our perspective appeared to be standing on the bridge’s far wall, until he vanished. I almost screamed to Donna, “look, a diver jumped,” as his silhouette splashed into the river. We had just witnessed the first dive of the tourist season on this Labor Day holiday.

Afterwards we visited the early 17th century Koski Mehmed Pasha Mosque, where it’s possible to climb its 30m (98ft) tall minaret for panoramic views of Mostar and the river. We also viewed the wrenching exhibits at the Museum of War and Genocide Victims, the only such museum we visited while in Bosnia & Herzegovina. It gave us tragic eye-opening, first-person accounts of life in Mostar when it was under siege.

The next morning on an early morning walk before Mostar awakened, I came across one of the town’s tagged stray dogs, a large black sheep dog, semi-asleep on the bridge’s highest point. He struck me as the reincarnation of an ancient watchman guarding the entrance to Stari Grad. He opened his eyes, but did not move, having determined I was not a threat, and I passed quietly.

Beyond the old town we found Mostar to be a wonderful compact cosmopolitan city with cafes and large colorful street murals in some neighborhoods. The walk along Alekse Šantića Street, a former frontline in the war, to the Cernica neighborhood is full of mural paintings. It was an initiative in 2012 by Marina Mimoza, a prominent cultural activist and artist who sought to heal the wounds of war and promote reconciliation through art “transforming ruined, bullet-ridden buildings into a vibrant cultural hub, and open-air gallery.” Since its inception the event has grown into The Street Arts Festival Mostar which turns the city into a colorful canvas each summer for invited artists and performers, typically in June or July.

Several tourist attractions nearby beckoned to us. First Fortica Hill, on the east bank of the Neretva River where the Skywalk, a glass bridge, has been open since 2021. From its height there’s a commanding view of Mostar and an Instagram worthy “We Love Mostar” sculpture. Amazingly, there was no entrance fee for the Skywalk, and there’s a small restaurant with a great view from its terrace.

Within walking distance of the Skywalk were the late 19th century ruins of an Austro-Hungarian stone fortification that had sweeping views north to the mountains on both sides of the Neretva River Gorge.

Later that afternoon we headed fifteen minutes south of Mostar to the orthodox Žitomislić Monastery, dedicated to the Annunciation of Mary. The church on the site was constructed upon the ruins of an earlier house of worship in 1566 with the surrounding monastery buildings taking another forty years to complete. It was a major spiritual center in the 16th and 17th centuries, hosting a large library, a scriptorium, and beautiful iconostasis. At the height of its existence the monastery was supported by large land holdings that included vineyards and orchards worked by the monks themselves. During World War II the entire brotherhood of the Žitomislić monastery were killed by local fascist troops allied to the Axis Alliance, and the complex was severely damaged and looted. Rebuilt after World War II, the monastery was again burned, but the church was savagely destroyed with explosives, reducing it to rubble during the 1990s Bosnia War. The original stones of the church were reused during its reconstruction in 2002 to recreate its earlier appearance, and it was reconsecrated in 2005.

We arrived to the monastery just as a tour bus finished disgorging its passengers. We dislike crowded sites, so we decided to explore the new monastery’s museum first, which had a small collection of ancient manuscripts, books, and liturgical objects, as well as a collection of some of the region’s oldest surviving icons. The works transcend several artistic styles from traditional Byzantine, featuring austere lines and dark color, to more graceful interpretations as Venetian and Baroque influences reached the Balkans. During exploration of the museum’s gift shop we discovered that the resident monks still make a traditional walnut liqueur called Orahovača. It’s made by soaking green, unripe walnuts in plum brandy with honey, citrus and spices like cloves and cinnamon. It is usually enjoyed chilled as a digestif after meals, or to treat stomach ailments. It was very tasty and we enjoyed the small bottle we purchased throughout the trip.

When the tour group departed, we entered the foyer of the church where a 200 liter, (50 gallon) stainless steel drum of what we assumed was holy water stood in the corner, available to fill your water bottles from. Entering the sanctuary revealed a stunningly beautiful space where every surface was covered in rich iconography.

A short drive away, but a long walk from the parking area was Blagaj Tekija, a historic Sufi Dervish monastery constructed in the early 16th century at the foot of soaring 240m (787ft) sheer rockface next to a karst cave. The cavern shelters a spring called the Vrelo Bune which is the source Buna River. It’s a dramatic setting. From its banks we watched visitors take small boats rowed by local men a short way into the mouth of the cave to see its large cavern. Professional divers have explored the dark cold water of the spring to a depth of 150m (492ft), but the total depth of the spring remains unknown. We enjoyed a late afternoon dinner at one of restaurants along the river’s edge. It was a very tranquil setting with ducks lazily paddling about on the softly gurgling water as it glistened in the bright sun.

Heading back to Mostar we made one last stop at Objekt Buna in Gnojnice. It’s an unofficial tourist site where visitors are semi-discouraged by a decrepit incomplete fence to not enter this Cold War era secret aircraft bunker. Located across the main road from what is now the Mostar International Airport, the military bunker was constructed into the side of a small hill in 1969 to shelter up to twenty planes and helicopters from attack. It was abandoned after the Bosnia War and is now a graffiti covered relic of the communism of Tito’s Yugoslavia. Outside the bunker the hillside was covered with wild poppies.

Mostar was especially enchanting in the evenings. Across from the small beach under the bridge where the boat rides launch from, we were surprised to see so many photographers lined up with their cameras mounted atop tripods placed, we hoped, firmly into the riverbed. Along with us, they were all intent on capturing the ultimate night picture of Stari Most as darkness fell. There were many previous attempts to build an arched stone bridge across the river, but all had failed, to the frustration of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. In 1557 he commissioned Mimar Hayruddin, a former apprentice to Istanbul’s grand architect Mimar Sinan to build a single arch bridge, but legend says the Sultan threatened him with death if his design collapsed. Fearing the worst as completion of the bridge neared in 1566 the architect reportedly prepared his own funeral shroud, expecting to be killed when the scaffolding supporting the bridge was removed. But to everyone’s relief, the 29m (95 ft) span, the widest man-made stone arch bridge in the world at the time, held firm. A marvel of engineering, the original stone structure stood for over 450 years until it was destroyed during the 1990s Bosnia War.

For our last day trip from Mostar we headed to Kravica Waterfall, but we rarely go directly to a destination, as there’s always other sites of interest along the roundabout routes we choose. Forty minutes south of Mostar we stopped at the Church of St. James in Medjugorje, a modest Bosnian town with about 4,000 people living in it. The catholic church was started in 1934, but its construction was interrupted by WW2, and religion was suppressed in Yugoslavia’s early communist years until authorities loosened their policies toward religious institution. The church was allowed to be completed and consecrated in 1969. But the quiet town suddenly rose to world-wide fame when six young people claimed to have seen the Blessed Virgin Mary on June 24th, 1981 on Crnica hill. Subsequent apparitions appeared to the children in different locations around the small town, and eventually in the church. The Virgin Mary’s visitations, with her messages emphasize reconciling with God, reading scripture, and encouraging peace are said to have occurred daily since then. And Medjugorje has grown into the third most visited pilgrimage site in Europe, after Lourdes in France and Fatima in Portugal, receiving over 40 million pilgrims since 1981.

When we arrived an outdoor mass was in progress behind the church in a large park-like setting; thousands of pilgrims were seated along rows of permanent benches or stood nearby. Around the front of the church folks prayed before a statue of the Virgin, as another mass was underway in the sanctuary.

Continuing our journey we headed to the Fortress of Herzog Stjepan Vukčić Kosača. Set atop a towering hill, the medieval 15th century castle was an important stronghold of the Kingdom of Bosnia as the Ottoman Empire expanded across the region. Kosača’s title “Herceg” (Duke), was also the name of his expansive domain which later became known as Herzegovina. Unfortunately, there was a large sporting event being held the day we visited, which would have required us to park at the bottom of the hill and walk to the summit. This would have taken too much time away from the rest of the day, so we contented ourselves with photos of the mighty stronghold from the foot of the hill.

The Trebižat River was full from runoff from recent heavy spring rains across the region and the Kravica Waterfall was the beautiful beneficiary. The spectacular bridal veil fall is 120m (394ft) wide with a cascade that drops 25m (82ft) into a crystal-clear turquoise basin. Local boatmen can be hired to row folks closer to the falls to hear the thunder of the water and get soaked in mist. A few swimmers were daring enough to brave the cold water.

There was plenty of parking near the park entrance and we opted for the ticket with the tourist train. This is especially helpful for folks like us with bad knees; the other alternative is a walk down many steep stairs, but be prepared for a vigorous climb up. Along the water edge there are three outdoor restaurants that are seasonally open. If pursuing waterfalls is your thing, another smaller cascade, Koćuša Waterfall, is 30 minutes away to the northwest.

The last stop of the day on the way back to Mostar was the ancient fortified stone village of Počitelj along the east bank of the Neretva River, that’s a tentative UNSECO site. Our descent into the town was down a narrow single-track lane, with occasional pullover spots in case you encountered any oncoming cars. At its bottom was a small plaza with a few restaurants and a tourist shop, from which the village spread dramatically up a steep hill. Founded in 1383 by Bosnia’s King Tvrtko I, the village was also a strategic stronghold and administrative center of the Ottoman Empire for 400 hundred years after its conquest in 1471, having a large mosque, hammam, madrasa, and a clock tower to reflect its importance as a governmental seat.

We entered the old town through an arched gateway. Under an ancient watch tower we spotted the largest fig tree we had ever seen, growing spectacularly from between stones of tower’s wall. If the tree ever fell, we were sure the tower would also collapse. Though there were several other tourists about, and signs that some of the old dwellings had been gentrified as vacation homes, the village felt as if it had been forgotten in time and abandoned; the aftermath of the 1990s Bosnia War.

Reaching Pašina tabija, a restored tower along the upper defensive wall, we were rewarded with a fantastic panorama of the village and the Neretva. Renovation to the tower included a glass walkway along the ramparts and a large deck to be used as a venue to host summer sunset concerts. Our late afternoon visit to Počitelj was the perfect way to end our time in Bosnia & Herzegovina, a destination we founded to be very charming and intriguing.

The next morning as we departed Mostar I promised that we would drive straight to Split, Croatia. “We’ll only stop for coffee, right?” “Yes, unless the steering wheel guides me like a Ouija board to some interesting locations.” I winked.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna