There’s a saying in the low country, that “summer in Georgia is like living on Hell’s front porch.” Our winters here are usually very mild, and our neighbors tell us a dusting of snow falls about once every 13 years, and it melts away in hours. But this year 3 inches of snow fell and stayed frozen on the ground for 4 days. The counties along the coast and in southern Georgia can’t cope with this type of “unusual weather phenomenon,” and declared a state of emergency. Schools were closed, and folks were advised to stay off the roads. Traffic came to a standstill on Interstate 95 due to the icy roadway and was shut down for 2 days. State Police rescued stranded truckers by using ATVs. Our neighbors shared, “When it snows like this in Georgia, you know Hell has frozen over!”

Fortuitously, months earlier four of us from our lake community had booked a flight to Hawaii that departed the same day the runways at the Savanna Airport were cleared of ice and ready for business again.

The balmy air was a welcome reprieve as we descended the stairs from the plane onto the runway in Kailua-Kona, on Hawaii Island or as the local folks like to say, The Big Island. But we were overdressed and overheated by the time we reached the baggage claim area and headed to the restrooms to strip off layers of now unseasonably warm clothing.

When we arrived at the Budget Car Rental office the queue was already out the door, and we watched our first Hawaiian sunset from the waiting line as the sun’s dying rays silhouetted the palm trees. This was not the romantic drinks-on-the-beach sunset we had envisioned for our first night on the island. The problem was a severely understaffed rental counter which gave priority to members of the company’s Fastbreak Program. We finally figured this out after waiting two hours, with more than one hundred other folks in a queue that now wrapped around the building. Donna realized we could download their app and take advantage of the expedited checkout program, and signed us up on the spot. As we switched lines, we shared our tip with folks around us, and we were headed out to our car within minutes. Donna acknowledges a twinge of guilt as we sashayed past all the other poor folks still stuck in that dreadful line. We’ve used Budget Car Rental flawlessly many times, but this was a horrendous experience. Fortunately, our lodging for the week at a Hilton property in Waikoloa was only a 30-minute drive north on Rt19.

Beyond the reception desk, the dancing patterns of light off the ripples of the hotel’s dramatically lit pool looked enticing. But after a long day of flying we needed a good night’s sleep.

The next morning we were up with the sunrise and out for a walk after a quick cup of coffee. The day was beautiful and there were many other like-minded couples out and about following the sidewalk that looped between the buildings of the sprawling resort.

Budha Point, a tranquil scenic spot on Waiulua Bay, that overlooked the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, was our destination. We visited here several times over the week and spotted whales breaching offshore a number of times.

It was less than a mile walk from our room through the beautifully manicured landscaping which coursed through the jagged lava fields that surrounded the Hilton Waikoloa Village, a sprawling complex with a tramway and footpaths connecting several towered hotels and pools along the seafront and the site’s lagoon.

Hawaiians have a great reverence for the ocean, and one of the wonderful things about the state are its laws that guarantee folks have a right of access along the beaches and shorelines, and that private property owners cannot obstruct access to it.

A little segway here: Hawaii is costly – think San Franciso or NYC expensive! The cost of parking is outrageous across the island, with residents parking for free and rental car drivers paying a high hourly rate at parking kiosks. Hilton guests staying in their premiere hotels around the resort’s lagoon or visitors wanting to attend the Legends of Hawaii Luau are charged $48 per day or $8 hourly for self-parking, and $55 per day for valet parking. Fortunately, the hotel we were staying in was farther away from the action and included free parking.

There was also a free shuttle bus that connected the hotels, shopping and restaurant courtyard within the complex. Several small free Beach Access Parking lots, which are closed to overnight parking, are across from excessively expensive Waikoloa Village parking lot.

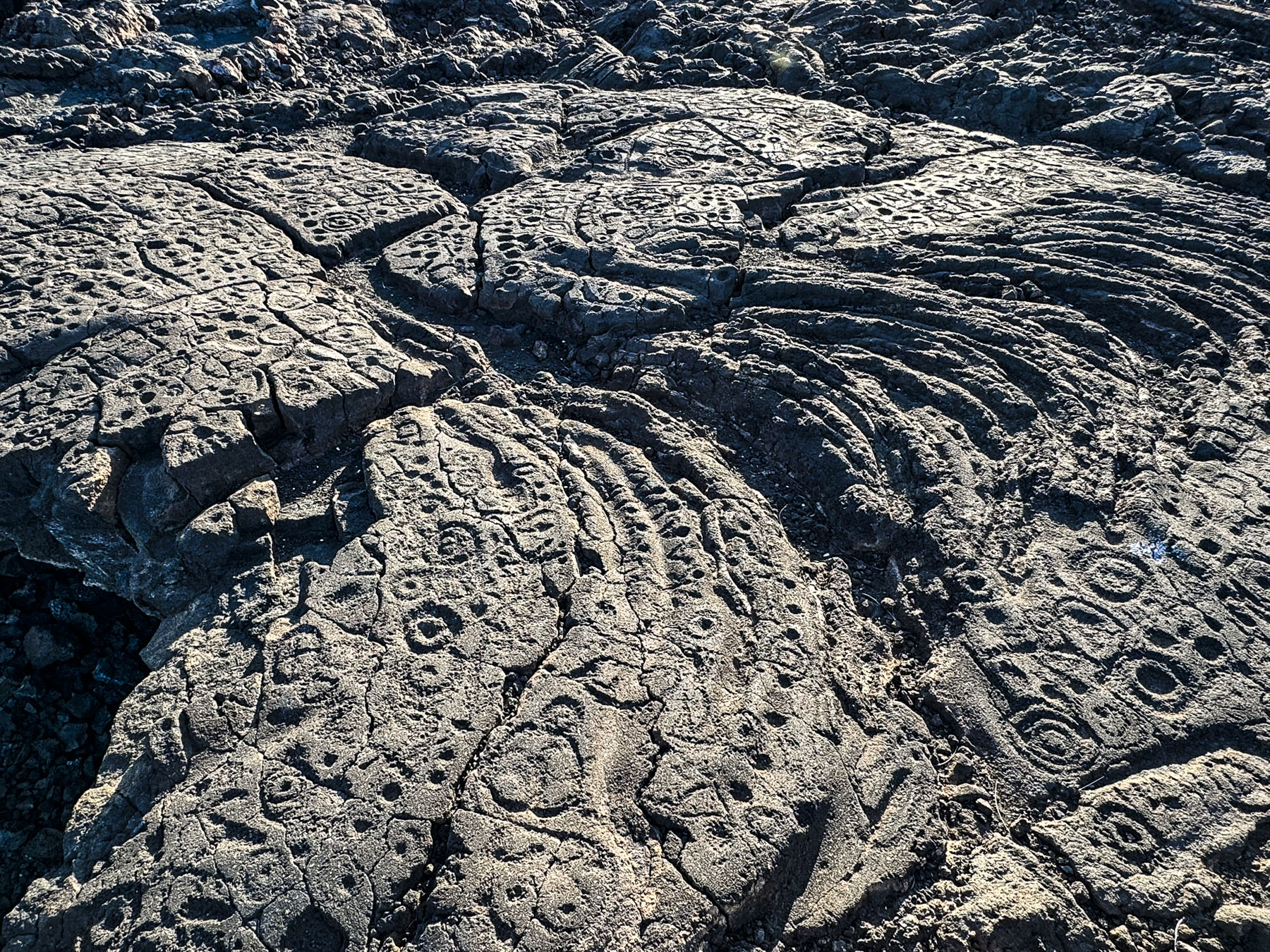

Continuing our loop around the resort we came upon the Kings Highway Foot Trail, part of the Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail, a 175-mile narrow footpath that follows an ancient trading and communications route, through rough lava beds. Starting at the farthest spot north on the island, Upolu Point, the trail which dates from the 1500s, connected the ancient Polynesian fishing villages and religious sites along the western and southern coast of Hawaii island to the farming villages in the highlands. In places like the Waikōloa Petroglyph Reserve, ancient messages were carved into the lava stones.

Dinner and watching the sunset from the Lava Lava Beach Club on ʻAnaehoʻomalu Bay is a pleasant nightly ritual for many who visit the area.

We could have spent the entire week lounging by the pool, but that’s not really us, so we planned several road trips around the island. We had driven to the hotel in the dark two days earlier, and the area around the resort was a mix of verdant greenery and sporadic patches of lava. Exiting the hotel complex onto Rt19 revealed an immense Martian-like terrain of arid inhospitable lava fields that stretch for dozen of miles down from the 4205m (13,786 ft) tall snowcapped summit of the dormant volcano Mauna Kea, and Mauna Loa, the world’s largest active volcano that sits 4170m (13,680ft) above sea level. They represent just one of the 11 climate zones found on the island. Which means when you circumnavigate the diverse landscapes of the island, you can experience everything from lush rainforests to arid deserts.

A short part of our drive that morning was through a landscape that reminded us of the American Southwest as we headed toward Hapuna Beach, the longest and widest stretch of white sand on the island. It consistently gets ranked as “one of world’s best beaches.”

The boulders of ancient lava, from the now extinct Mt Kohala, carpeted the shoreline at Kapa’a Beach Park. An estimated one million years old, it’s the oldest of the Big Islands’ six volcanoes, and last erupted 120,000 years ago.

Rain clouds threaten us as we stopped for coffee at the Kohala Coffee Mill, in the small town of Hawi, to indulge in our “drive a little then café,” philosophy. Rain poured for a few minutes as we sipped our coffees at tables under a covered sidewalk, and waited for the shower to pass. It’s a quiet one street town with a few small shops, galleries and artwork along the street. Away from the large resorts on the Kona coast a little bit of “old Hawaii,” shined through here.

A few minutes farther up the road we stopped in Kapaau at the Statue of King Kamehameha that commands the slope in front of the Old Kohala Courthouse. Ancient Hawaiian legends had foretold, “a light in the sky with feathers like a bird would signal the birth of a great chief.” Halley’s comet passed over the isalnds in 1758, the year Hawaiians believe Kamehameha was born. For centuries warfare between clans and inter-island raids were widespread throughout the Hawaiian archipelago. Kamehameha with an army of warriors on hundreds of peleleu, double-hulled 70ft long war canoes, sailed between the islands. In a series of battles he defeated the opposing chiefs on Hawaii, Oahu, Maui, and Molokai and united the islands into the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi in 1795. By 1810 the islands of Lanai, Kauai, and Niihau voluntarily joined the kingdom.

Leaving Kapaau we followed Rt 250 up into the Waimea highlands beneath Mt Kohala, a vast grasslands atop a long ridge, and home to the 135,000-acre Parker Ranch, one of the oldest and largest cattle ranches in the United States. From the road distant views of the west coast of the island were abundant. As we descended into Waimea the summit of the dormant volcano Mauna Kea poked through the clouds.

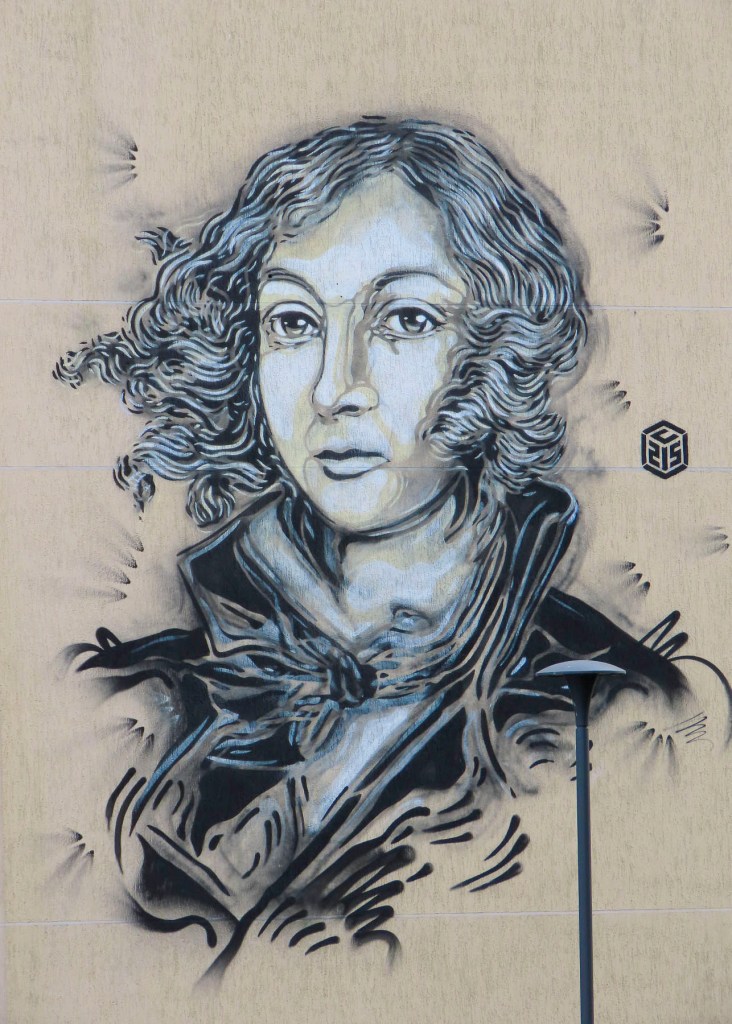

Waimea is the center of the Big Islands’ paniolo (Hawaiian cowboy) country. It’s a large pretty town, with several old historic churches, colorful street murals and a tall cowboy boot marking the entrance to a shopping center. The first cattle on the island, 11 cows and 1 bull, were given to King Kamehameha by the British Naval Officer, Captain George Vancouver, in 1793. The king prohibited the islanders from slaughtering them and the small herd was left to freely roam the highlands.

In 1803 King Kamehameha received, from an American trader, the first horses to arrive on the island. The king invited vaqueros from Spanish California to the Big Island to teach some islanders cattle herding and roping skills. Eventually, the taboo against killing the cattle was lifted in 1830 by King Kamehameha III, when an estimated 25,000 wild cattle became troublesome as they destroyed farmer’s crops. Some of the cattle would be herded into the sea where they were swum out and then lifted onto waiting freighters and transported to the other islands. Hawaiian paniolos grew to be accomplished riders and over the years, have competed in numerous rodeos and world steer-roping championships. In 1999, Parker Ranch paniolo Ikua Purdy was inducted into the National Cowboy Hall of Fame. We had hoped to attend a Paniolo BBQ at Kahua Ranch for a night of good food and cowboy stories, but the weather the week we were on the island was just too iffy for us to commit to it.

Oustide of Waimea on the Mamalahoa Hwy, the ring road, we headed to the eastern, or windward side of the island and traveled through verdant landscapes of thick forests and jungles, the beneficiaries of the 130 inches of rain that this side of the island annually receives from the tradewinds that bring moisture in from the Pacific Ocean. It’s a sharp contrast to the arid western, or leeward side of the island that receives only 18 inches of rain.

The overcast sky persisted as we drove down a twisting road through a rainforest to Laupāhoehoe Point. It’s a small, beautiful peninsula, with a rough lava rock coastline. The ocean swelled and crashed against the coast with a ferocity that the beaches on the west side of the island don’t experience, unless there’s a storm.

Saffron finches scooted around the undergrowth near the water’s edge. Over the horizon Baja, Mexico was 2,000 miles away. Things are not always wonderful in paradise and a memorial commemorates the tragic deaths of 20 schoolchildren and 4 teachers who drowned as their school was swept away in the giant waves of a tsunami that pounded the northeastern shores of the Big Island on April 1, 1946. Farther south in Hilo 159 people drowned and 1,300 homes were swept away.

The Big Island has over 100 waterfalls with the tallest, Waihilau Falls at a lofty 792m (2,600ft) tall, hidden away in the remote Waimanu Valley. Some serious trekking through the rainforest is required to reach them, while there are others that are way easier to view. As much as I liked the idea of an expedition through the tropical forest with my crew to see this spectacular waterfall, they can be a mutinous car full towards happy hour. So, we opted to seek out some of the more readily accessible ones during our week on the island.

Continuing south on the Mamalahoa Hwy we stopped to view the cascading Triple-Tier Umauma Falls, thundering loudly from all the rain that had fallen lately. It’s on private property, so there was an admission fee, but they did have really tasty coconut, pineapple and mango ice-cream.

We ended our day with drinks and dinner at Jackie Rey’s Ohana Grill in Hilo. It’s interestingly set in an old bank building across from some street murals. Our dinners from the happy hour menu were delicious and quite filling. In our opinion it was one of the best values on the island, and we did in fact eat there twice. Occasionally, a feral goat or donkey would be illuminated by the car’s headlights as we followed Saddle Road across the center of the island. At one point we reached an elevation of 2,021m (6,632ft) as we passed between the summits of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa. On the downhill side we could have coasted all the way back to the hotel.

Two days later we headed to Kona for their Farmer’s Market. We very much enjoy wandering about the stands at a good street market. Sadly, the Kona market was a huge disappointment, with only a handful of vendors selling tourist souvenirs and clothing. Only one stand sold local fruit and vegetables, which we did purchase to enjoy back at the hotel. Across the street we had breakfast at Papa Kona Restaurant & Bar, which had a spectacular second-story balcony perched right above the rocky oceanfront, where fishermen were casting into the surf.

Our ambitious plan for the day was to follow the Hawaiʻi Belt Road, Rt11, to the Hikiau Heiau temple on the opposite side of Kealakekua Bay from which Captain Cook landed in 1779, then hit a number of other interesting spots as we continued south to Ka Lae, or South Point as it is also known, before swinging around to the eastern side of the island, and ending our day on the volcanic black sand of Punaluʻu Beach.

Cook happened to sail into Kealakekua Bay during a Makahiki festival, a religious festival to appease the Hawaiian deity Lono, who in legend returns to the islands on a large ship. Timing is everything! Cook lucked out, his skull could have hung with other victims who had been sacrificed to appease the wrath of their deity, amidst the towering fierce tikis which portrayed Lono. The High Chief of the island ceremoniously welcomed the captain and lavished him with gifts of feathered capes, helmets, lei, and tapa cloth along with hogs, taro, sweet potatoes, and bananas. The bay is a tranquil spot now, but during Cook’s visit it would have been filled with hundreds of islanders on wa’a, outrigger canoes, and surfboards.

Continuing south we reached the Pu’uhonua O Honaunau National Historical Park, site of an ancient religious sanctuary. Few spots on the Big Island resemble paradise more than Pu’uhonua O Honaunau, with its brilliant white sandy beach lined with swaying palm trees, along a cove with clear blue water. For centuries before the Christianization of the island started with the first arrival of protestant missionaries in the 1820s, it was also known as the City of Refuge, where islanders who broke a kapu, an ancient law, could flee to safety to escape the death penalty their action incurred. Here an offender of the ancient ways would seek absolution from a high priest and be free to return to their village. Villagers and defeated warriors could also seek sanctuary here during periods of inter-chiefdom wars.

The most important structure on the site is Hale o Keawe, a stone and thatch royal mausoleum that contained the remains of 23 deified high chiefs. Around it, fierce looking tiki statues serve as guardians of the dead, and embody the spiritual power of the kapu.

The site also has two Hawaiian hale houses, open sided bamboo and palm frond or pili grass covered structures. Multiple hale houses were built in a village for specific uses: men’s meeting house, cooking house, separate eating houses for men and women, workshop and canoe house, and a menstruation house.

Uphill from Pu’uhonua O Honaunau we visited the Painted Church, aka St Benedict Catholic Church. It’s a simple wooden church that dates from the 1880’s, and easy enough to just drive by unless you know it has a spectacularly painted interior.

While it’s not Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel, the message is the same with every surface of the interior illustrated with stories from the bible. It was all the work of one creative Belgian priest, Father Jean Berchmans Velghe. He painted these religious murals between 1899 – 1902 for his, largely illiterate congregation.

The Coffee Shack, a laidback breakfast and lunch restaurant on Rt11 in Honaunau-Napoopoo, was recommended to us as a nice place to eat. Parking was a little difficult in their small lot, and the place doesn’t look like much from the outside, but inside they have a lanai, an open sided porch, with panoramic views over the hills leading down to the Kona coast and Kealakekua Bay. We had just gotten seated when the power went out, something that we were told happens quite frequently across the island, and the server informed us “the cook doesn’t open the refrigerator when this happens, so we only have pastries, and the coffee is still hot.” It wasn’t much of a sacrifice to content ourselves with coffee and luscious pastry.

After a snack we optimistically continued south in search of an open restaurant, and we were not having much luck. Talk of mutiny was fomenting in the back seat. This whole southern coast lies in the shadow of the Mauna Loa volcano. Past the town of Ocean View the road crossed scars of ancient lava flows that stretched from the volcano’s summit to the sea. Fortunately, we came upon the El Encanto Food Truck, which had its own generator, and was busily serving a long line of hungry patrons at its window. Our lunches were delicious! The mutiny was postponed.

The power outage also affected gas stations along our route. With the afternoon sky darkening we decided to forego visiting South Point and continue on to Punaluʻu Beach. It’s a graceful crescent shape, and we are sure on a sunny day its volcanic black sand beach lined with coconut palms would be stunning, but this afternoon it looked foreboding with a gray sea sweeping its shore, more apropos for the scene of a novel’s fictional shipwreck, than a place to sunbath.

Rain was threatening now, but as we walked back to the car, Donna was waving excitedly to us. On the beach were three large green sea turtles in a roped off nesting area. Native to the Hawaiian archipelago, they are the largest sea turtle that nests on the islands and are symbols of good luck, wisdom, and protection. It was such a pleasure to see them.

The Hawaiian legend of Kauila, tells of a mystical turtle born on the black sands of Punalu’u, who had the ability to shapeshift into a human to play with the islander’s children that came to the beach, and to protect them from the dangers of the ocean. Heavier rain sent us hurrying back to the car. It was a long but rewarding day; we agreed that the spotting of the turtles was a real highlight of the trip.

Our pursuit of waterfalls continued the next day. Recrossing the mountains during the day cast a new light on the arid windswept heights as we ascended the road under snowcapped Mauna Kea then descended towards Hilo and into verdant greenery of the eastern side of the Big Island. It was a contrast equivalent to night and day, like our two drives across the island.

Roaring from all the recent rain, Wai’ale Falls was easily seen from the bridge over the Wailuku River. There’s not any official parking, so folks just park along the side of the road and walk out onto the bridge. There is also a rough trail, through thick undergrowth, up and over the road embankment that leads to the upper falls. We followed the footpath for a while until it narrowed along the edge of a fall-off, and we decided to turn back. Though some younger, more adventurous folks had reached the top of the 17m (55ft) high falls and were fearlessly jumping into the pool below.

Downriver, Rainbow Falls, in Wailuku River State Park, was a short drive away. It’s known for, you guessed it, rainbows that frequently appear when the light is just right. The riverside park is quite pretty and has paved trails that overlook the falls where the river’s cascading water veils a shallow cave as it drops 24m (80ft) into a large stone basin created over the ages by erosion. “Legends say that the cave beneath the waterfall was the home of Hina, mother of the Hawaiian demigod, Maui.”

Our next “drive a little then café,” moment was satisfied at Coffee Girl, a cute café in a Hilo strip mall, on the way to Makuʻu Point.

Turbulent seas churned from storms blowing across the Pacific along with volcanic activity have prevented the creation of beaches on eastern coast of the Big Island. Dramatic volcanic cliffs and lava outcroppings line the windward coastline instead.

The next morning, we set out to find more ancient stone inscriptions at the Puakō Petroglyph Park, in nearby Waimea. The trail started in Holoholokai Beach Park, where there is a unique beach of black lava rocks mixed with white coral, and soon led to a gathering of petroglyphs.

The symbols were quite interesting, but it was obvious that the carvings were reproductions of ones that the trail led to. We followed what started out as a well-worn trail through a primeval forest full of twisted trees, until the trail seemed to vanish. It was a hot day, and we were concerned about getting lost, so we backtracked and turned our attention to discovering some of the smaller beaches near the resort.

Puako Bay is a few minutes south of Hapuna Beach, the island’s largest stretch of sand, which we had visited earlier in the week. It’s a tranquil bay with many public access trails from the road to small sandy beaches, and rocky coves, that folks like to snorkel in.

There was a small beach next the Hokuloa Church that offered a nice view of the bay with Mauna Kea in the distance. The church was built with lava rock and then whitewashed in the late 1850s.

Kikaua Point Park was south of our resort and access to it was, surprisingly, through a gated community. Where folks are allowed access to the beach after getting a parking permit from the security guard. A long concrete walkway led from the parking lot through a boulder strewn lava field to a lovely palm treed beach. Folks were enjoying the breeze in the shade of the trees and swimming in the warm water of an almost completely circular and shallow sandy bottom cove. It was the perfect spot to spread our towels out and go for a swim.

We only scratched the surface of this big, beautiful island. And if we ever return we would definitely go to see the array of telescopes at the observatory atop Mauna Kea. The cost of living is very high on the island, with even locally caught fish, fruit and vegetables being expenses. Folks always say eat at the food trucks; while less expensive, their prices are steep too. So, if we ever return to the island – Donna furrows her eyebrows when I say this – we are packing snacks, several bottles of wine, a jar of spaghetti sauce and pasta, along with a couple of frozen steaks that should be perfectly thawed by the time our flight lands.

Till next time,

Craig & Donna