Traveling north or south in Albania is easy, as the roads follow the lay of the land between mountain ranges that run parallel with each other. Heading east away from the coast towards villages and small towns farther inland is a bit more difficult. Destinations that appeared relatively close on a map, from a bird’s eye view, often became a driving marathon following routes north or south until the rugged massifs conceded a mountain pass that was suitable for a road to be constructed across. Road tunnels did not exist during the communist dictatorship of Enver Hoxha. Though tunnels were extensively built across the country as part of Hoxha’s “bunkerisation” program, which constructed an estimated 173,000 military bunkers across the country. Fortunately, as tourism has blossomed, Albania has invested in its roadway infrastructure, and our route to Gjirokaster from Sarande benefited from it. We were able to traverse our way across the deep gorges of the Mali i Gjerë range along the recently opened Kardhiq-Delvin road and scoot under the 7,000 foot high massif through the mile long Skërfica tunnel. It was a beautiful and dramatic stretch of roadway with expansive views at every curve.

There is nothing subtle about Gjiokaster; it’s a gorgeous place. The ancient town’s beauty startled us like a slap across the face, as soon as we turned off the main road. The town rose from the Drino River valley up the steep eastern flank of the Mali i Gjerë mountains. Large fortified tower houses, known as kullëh, dating from the 17th and 18thcenturies, followed the topography and were built randomly across the slope, as if they were stepping stones across a river. These small family fortresses were built to protect against foreign invaders and violent feuds between Albanian clans.

Gjirokaster Castle centered the landscape atop a long thin ridge that protruded from the lower slope of the mountain. At the castle’s apex the red and black flag of Albania blew full out in the wind, its colors vividly contrasting against the verdant hillside.

Little is known about Gjirokaster’s early history, though archeological evidence suggests that the area has been inhabited since the 5th century BC, and that a smaller fortification in the 2nd century BC existed where Gjirokaster Castle now stands. Gjirokaster isn’t mentioned in any historic records until 1336 when a Byzantine chronicler noted it. By the early 15th century, the region was under Ottoman rule and Gjirokaster was an administration center. The town’s residents prospered from their industriousness in embroidery, silk, wool, flannel, dairy products, and livestock. The notorious Albanian brigand, warlord, and Ottoman governor, Ali Pasha of Tepelenë – more about him later – acquired control of Gjirokaster in 1811 and built the magnificent castle/fortress that crowns the city.

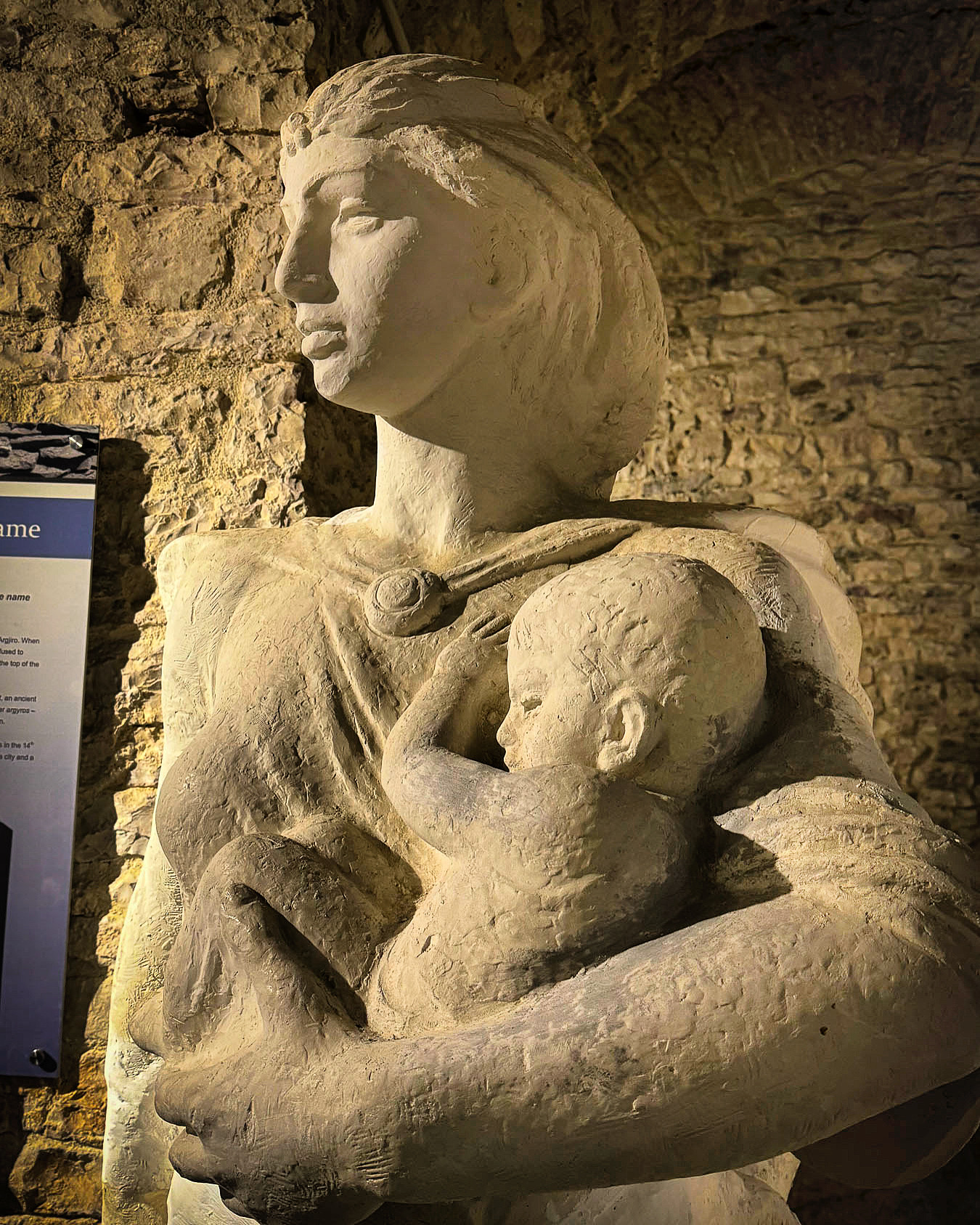

We were able to find parking on the street near the castle’s entrance, just after the site opened. Unfortunately, we were in the ticket queue behind a large student group on a school outing. But the line went quickly, and the students soon vanished into the cavernous lower level. Its high arched ceiling resembled the interior of a medieval cathedral more than any fortress we’ve toured previously. This was the ancient storeroom, barracks, and stable area. Today the open undercroft is used to display a collection of antiquated artillery pieces, tanks, and antiaircraft guns, that have been used in the conflicts of the past 200 years that have engulfed the country. Farther on there are rooms with exhibits about Albania’s complicated history over the centuries, the WWII resistance and folklore heroes. Especially moving was the tale of legendary Princess Argjiro, who, with her young son in her arms, is believed to have jumped from the castle wall to their deaths, to avoid imminent capture by the Ottomans.

Not wanting to miss anything, we climbed stairs in the museum and followed signs to a small military museum, that had an extensive collection of ancient swords, rifles and pistols. But, on our return walk we noticed a small discreet sign that pointed to the prison.

This part of the fortress was added in 1932 by King Zog, who ruled Albania from 1922-1939. The later communist regime under Hoxha filled it with political prisoners. It was a chilling experience walking the hallways and entering the cells where prisoners slept on the floor, without blankets, through the cold winter months.

The top level of the castle features a clock tower and also offers a fantastic 360-degree panoramic view of the Drino River and the Mali i Gjerë mountains.

Oddly, on display is the fuselage of an American fighter jet, whose pilot flew off course while flying over the Adriatic Sea in 1957 and violated Albanian airspace.

The pilot was forced to land at Tirana airport by two Albanian jets that intercepted it. These were the Cold War years, and the incident fueled Enver Hoxha’s paranoia that the West was going to invade Albania at any moment. He also used the event to further justify his “bunkerisation” of the nation. The castle is also the amazing venue for Albania’s National Folklore Festival. This event is held every five years and was first orchestrated in 1968 to celebrate the despot’s 60th birthday, in his hometown. An Albanian postage stamp, with his portait, issued in1968 also commemorated the occasion. After the castle we walked a short distance towards the mountains, to lunch nearby at Taverna Tradicionale Kardhashi. The restaurant is just 200ft past the intersection where several restaurant hustlers tried to steer us to different establishments. The owner was a gregarious fellow, and delights in sharing the tasty Albanian specialties that his nënë and gjyshja must have created in the kitchen. Our lunch was wonderful and very reasonably priced.

After lunch it began to rain as we headed to check-in at our lodging for the night, the Hotel Bineri. The hotel is conveniently located near the center of the Gjirokaster’s old town, and we specifically chose it because they offered parking. A huge part of Gjirokaster’s charm comes from its meandering archaic footprint that follows the natural lay of the land, but driving to the hotel along the town’s ancient cobbled alleys, that were built for horses drawing farm carts, was a nerve-wracking experience. Our mapping app was totally confounded by the one-way roads, and lanes wide enough to start down but then ended at a set of stairs or required K-turns to negotiate. We tried multiple routes. The fact that it was raining didn’t help. The one saving grace was we did not encounter any cars coming downhill as we were going up. This was such a relief as there was no room to pull over, and it would have required us to back down the alley. The lane ended as we reached the hotel. It was not obvious where to park, and we didn’t want to get ticketed, so Donna trekked up a tall flight of stairs to reception to inquire about it. It seemed the hotel was short staffed during the shoulder season, and the cleaning staff was manning the front desk. Eventually it was conveyed that Donna should inquire at the bar, across the street from the bottom of the stairs. “No problem, park behind my SUV over there.” But this was a difficult task that required us to pull forward and then reverse up a switchback driveway that paralleled the alley we had just driven up. There was barely enough room to squeeze by the SUV and there was no wall to prevent me from mistakenly putting two wheels over the edge. And did I mention it was heavily raining?

The Bineri is a very stately hotel, and our room was very nice, with great attention paid to fine woodworking throughout. However, we were dismayed when we realized a rambunctious student group shared the floor with us. After dinner the rain had stopped, and we wandered along the cobblestones of the five lanes that converge in the center of the old town. The stones still glistened from the earlier rain and reflected the lights of the shops and restaurants still open. The clock tower at the castle was illuminated against a royal blue night sky.

I’m hard of hearing, but Donna is a very light sleeper, and we inquired about a room change to avoid the loud students, only to be told the hotel was full. They graciously offered us a bottle of white wine and delicious orange peels soaked in honey for dessert, which we enjoyed in the restaurant until it quieted upstairs. Considering the price of our room, we are not sure if this was fair compensation for a poor night’s sleep. It was the third week of April, and overnight the rain had turned to snow on the higher elevations of the mountains around Gjirokaster. They brilliantly glistened in the morning sun. A week earlier, when we landed in Tirana, it was 80F for several days.

Very often gas stations along the roads in Albania are attached to a restaurant, and sometimes there will be a hotel too. These are not the iconic American greasy spoons, associated with truck stops. We found them to be surprisingly nice places to dine, especially if their parking lot was busy. The BOV station on the way to the Castle of Tepelena, was an exceptional place to stop. We enjoyed coffee on their patio which had a tremendous view of the confluence of the Drinos and Vjosa River.

The Castle of Tepelena dramatically commands a cliff face above the Vjosa River Valley. It’s a supremely strategic location with views of the valley extending for miles north and south. The flat river plane was a natural highway that has funneled invaders into the Balkans since antiquity.

A Byzantine fort first occupied this spot and was later expanded by the Ottomans and Ali Pasha. Ali Pasha was a figure in Albanian history, with an interesting background story. He was born in 1740, nearby in the small hamlet of Beçisht, into a family of notorious brigands. He followed his family’s business plan until the Ottomans, who embraced a philosophy of if I can’t defeat you, I will employ you, hired him into the administrative-military apparatus of the empire. A savvy and talented individual, Ali rose through the ranks and was eventually appointed Pasha of the region, the Ottoman equivalent of a governor, in 1788. He benefited from Albania’s remoteness from Constantinople and governed the region as an autonomous despot intent on enriching himself and his clan. He was intelligent, charming, charismatic, ruthless, and brutal. Captured enemy leaders were roasted alive. Men from rebellious villages were executed, the women and children sold into slavery to intimidate other villages into submission during the day while he entertained the likes of British poet Lord Byron and the French diplomat François Pouqueville in the evenings. He was a political opportunist who allied himself with anyone he thought served his interests. By 1819 Sultan Mahmud II had had enough of Ali’s deceit. Ali was captured and shot after a long siege of Ioannina, in Greece. His head was sent to the sultan and was publicly displayed, on a platter, in the sultan’s Constantinople palace.

Sadly, only the defensive walls that encircled the 10-acre fortress remain. Its mosque, barracks, and stables, along with Ali’s palace, which Byron one described as “splendidly ornamented with silk and gold,” have been lost to earthquake damage, and battles during WW1 and WW2. Now streets lined with small homes course through the site. Tepelena itself is a quaint town that’s worth exploring.

We had gotten off to an early start, as our destination for the end of the day was the Melesin Distillery in Leskovik, near the border with Greece, which also offered stylish, luxurious rooms. It was only 56 miles, 90 km, from the Tepelena Castle, but with a break for lunch and a stop at the Kadiut Bridge in the Langarica Canyon, it would take all day.

From Tepelena we followed the winding SH75 south along the Vjosa River Valley. It was a beautiful stretch of road, and we stopped many times to take landscape photos along the way. The valley narrows near the village of Këlcyrë, where in 198 BC the battle of the Aous raged between armies of the Roman Republic and the Kingdom of Macedon. It was an epic confrontation, and “the river ran red with the blood of 2000 dead and wounded.”

Aous is the ancient name for the Vjosa River which originates in the Pindus mountains of Greece, but from the Albanian border to the Adriatic Sea it’s called the Vjosa. The 168-mile-long waterway and its many tributaries are among the last free-flowing, wild rivers in Europe. And since March 2023, 50,000 acres have been protected as the Vjosa Wild River National Park to ensure that the rivers within its boundary will never be dammed, mined, or dredged.

Across the river, overnight snow had covered the Nemërçka mountain ridges, and the pure white snowcap gleamed between a deep blue sky and verdant mountain slopes. On the other side of the road, we spotted the green domes of Teqja e Baba Aliut, a Bektashi (an Islamic Sufi mystic order,) pilgrimage site in the remote mountaintop village of Alipostivan. The site commemorates Baba Aliut, a ledendary figure who is believed to have ridden a white horse from Mecca to Albania, to save the country from paganism. Key supporters of the the Albanian National Awakening Ba Baba Abdullah, and Baba Dule Përmeti are also buried at the site. Knowing about the shrine now, I wish we had included it in our plans.

We reached Përmet around noon and headed to Guri i Qytetit, a very large bulbous rock that protrudes from the terrain along the river, like a wart on a witch’s nose. It’s a geological feature unique to Përmet with stairs that lead to the top, where we interrupted two young teenagers sharing their first cigarettes as they sat on the ruins of an ancient watch tower. There was a great view of the Vjosa River and the town.

Nearby we found Sofra Përmetare, a small restaurant that was booming with a Saturday lunch crowd, and we needed to have our coffee outside before an inside table was ready. Our lack of Albanian didn’t faze the owner, and he proudly called his son over to explain the menu to us. His English was excellent, explaining that he studied it in school and watched American TV programs. We really enjoyed Albanian food, and appreciated that vegetable dishes were always available, and that French fries didn’t automatically accompany every meal. In the more rural parts of the country it’s important to carry cash, as many restaurants, shops, and gas stations do not accept credit cards.

The side road cut through a wide valley planted with orchards and field crops. We were headed to the Ottoman-era Kadiut Bridge, built in the 1600’s across the Lengarica River as part of a caravan route that connected the Albanian coast through Përmet to Korce, Thessaloniki, and Constatinople. Locally, oxen laden with timber cut in the mountains hauled their loads to Përmet, the quickly growing regional center, over the bridge.

The old stone Ottoman bridges are truly graceful with their high arch design. But the real draw for folks to the bridge are the Llixhat e Bënjës, thermal hot springs at its base. Even in mid-April there was a sizeable crowd in various stages of undress enjoying the warm water.

On the Saturday afternoon that we followed the SH75 to Leskovik there was very little traffic, but we did notice a number of roadside memorials to the victims of car accidents. While Albanians are very friendly, they are extremely aggressive drivers who, I speculate, pour raki on the driver’s rule book, set it afire with a cigarette, and toss it out the window while they are driving. A newly paved roadway rose into the mountains and we stopped at a scenic overlook, where a historic plaque noted another Battle of the Aous was fought in the valley below the towering Nemërçka mountains in 274 BC between the armies of King Pyrrhus of Epirus (Greece,) and King Antigonus II Gonatas of Macedon.

The road wound, zigged and zagged, climbed, and fell through tall pine forests that covered the mountain slopes before it summited and continued its winding descent to Leskovik. The drive along the river and through the mountains was beautiful and the area is full of potential for outdoor enthusiasts to enjoy rafting, camping and hiking in the Vjosa Wild River National Park.

Under a stormy sky when we arrived, it was difficult to believe that the Ottomans established Leskovik as a summer resort for wealthy officials who owned estates in the region when it was under their control. Fortunately, we were pampered with a wonderful stay at the Melesin Distillery, truly a five-star boutique hotel in the wilderness of southern Albania. Its eight guest rooms upstairs are well designed, and nicely appointed with stylish furnishings, and great amenities.

The distillery makes raki with locally harvested grapes, and gin flavored with juniper berries hand-picked in the mountains. Grapes have been grown in the region for centuries and the area’s wineries were productive and known for producing a strong red wine from Mavrud, an indigenous grape varietal, during the communist years.

But after the fall of the regime in the 1990’s and the economic collapse that followed, many people moved away to find work abroad, and the vineyards surrounding Leskovik were abandoned or destroyed. The Melesin Distillery along with the Max Mavrud Winery are hoping to reinvigorate the area’s historic winemaking tradition. Our dinner was excellent, as was our breakfast the next morning. On the plaza in front of the distillery there is a fountain shaped like a wine cask at the base of a stately tree, and a statue of Jani Vreto renown as an important figure in the Albanian National Awakening in the 19th century, and his epic poem, Histori e Skënderbeut, History of Skanderbeg, dedicated to Albania’s national hero.

The Melesin Distillery in Leskovik was the perfect way station before we continued onto Voskopoja for its Orthodox churches, and Korce.

Till next time, Craig & Donna

P.S. We only scratched the surface of GjiroKaster, and should have planned for a two night stay in the beguiling town.